How Joe Campbell Found Himself $106,445.56 In Debt

By Not Understanding the Risks of Shorting Stock, He Lost Everything (and Then Some) In Minutes

One of the major themes running through my body of work, both on this site and in the past 15 years of writing at Investing for Beginners, can be summed up in the statement, “Know your risks”. I hammer it home all the time; “risk-adjusted return”, talk about remote-probability events, explaining how much of wealth building is learning to “tilt probabilities in [your] favor”, admonishment to never invest in something you don’t fully understand and couldn’t explain to a Kindergartener in a couple of sentences.

I want to teach you how to think for yourself, not what to think because history is never going to repeat itself exactly. Instead, you need to be able to identify risks and potential catastrophes that aren’t known or that haven’t manifested themselves in ways identical to the past. It’s the reason I encourage you to study financial history and not fall into the easy trap of recency by casting an eye solely over the last decade; to go back and examine valuation levels prior to the Great Depression, to look at how oil stocks or food stocks behaved between 1929-1933; to study the liquidation period during the 1870’s or the panic of 1907; to accept that a so-called outside context problem could present itself.

Put another way, some of the questions you should ask yourself when risking your (often hard-earned) money are:

- What could go wrong?

- Is there any way to mitigate this risk? (e.g,. finding a way to invest in a real estate project through a legal intermediary, such as a limited liability company, in which you maintain less than 20% equity so the bank won’t require a personal guarantee allowing you to put it into bankruptcy if necessary without exposing more than the value of your investment to wipe-out risk).

- If it went wrong, what are the consequences in absolute and relative terms?

- Could I live with them?

- Is there any way to reduce the consequences (e.g., buying a cheap out-of-the-money call to cap your potential losses as an offset to a short position if you are speculating a particular firm will fail or decline in market value)?

- What is the probability of the event coming to pass?

- Is there any way to decrease the probability (e.g., investors with $5,000,000 or more building their own index fund of directly held positions rather than buying into an index fund or ETF, the latter of which could suffer from a remote-probability embedded gains risk if other investors were to ever make a run on the fund)?

It goes back to the Benjamin Graham rule “at what price and on what terms?” [*See comment section.] The terms are just as important as the price. You look at successful business owners and this becomes readily apparent; things that others don’t even think about but that guide their decision-making process, like a financial company refusing to enter transactions that require posting of additional collateral in the event of a downgrade (since that is precisely the time when they are most likely to need cash), even if it means passing on an opportunity or refusing to hold cash reserves in anything other than U.S. Treasury bills. Such conservatism is mocked when times are good and nothing has gone wrong. It’s criticized as overly-cautious; nonsensical. Until it’s not. You should almost never accept non-compensated risks unless you absolutely must. At the very least, you should be aware of what they are and go into them with your eyes wide-open. That’s it. That’s the entire reason I sometimes point out structural, behavioral, or other flaws with certain products or services even they are otherwise very good. I don’t want you to be surprised.

In fact, Graham himself often talked about security selection inherently being an art of negation. An intelligent investor is looking for reasons not to do something, then deciding if they are deal breakers. He or she wants to know what could go wrong; what could cause losses; what could show up unexpectedly and destroy beautiful capital that could have produced passive income for your family to enjoy.

This Approach Causes Some People Significant Emotional Distress. If This Describes You, Change It. Your Life Can Only Be Improved By Protecting Your Family.

In my experience, this approach resonates almost immediately with certain people, especially those who have a deep-seated optimism. I’ve told you how I’ll pass on 99% of the things that come across my desk – even things that go on to make a lot of money – because I didn’t like the risk trade-off either in absolute terms or relative to whatever else I could get at the moment. It’s okay because, as I’ve also often said, there are always intelligent things to do. If you want to own stakes in publicly traded businesses, there are 30,000+ of them around the world, many being re-priced in near real-time. If you see an opportunity and are a good operator, you can start a business of your own. If those aren’t attractive, you can find a real estate property that offers a lot of intrinsic value relative to the purchase price or, alternatively, can be financed with an arrangement that gives you a lot of upside over a long period of time with little cash flow risk. You can lend money, either through securities such as bonds or certificates of deposit, or in directly negotiated instruments. On and on it goes. Each opportunity has potential downsides that are country-, market-, firm-, and transaction-specific. Hearing the negatives doesn’t in any way discourage this type of person because they look around and know the best investment of their life could be right around the corner. It’s this faith that makes it possible to refuse to settle; to not reach for yield or take on exposures that cause concern.

It also, in my experience, immediately repulses a small minority of people who don’t separate their egos from their ideas causing them to take any sort of acknowledgement of risk as a criticism of them, as a person; a personal attack or evidence of an ulterior motive. You saw it in the 1990’s anytime someone suggested buying Wal-Mart or Microsoft at 50x or 70x earnings wasn’t particularly intelligent. You saw it in the real estate bubble when people suggested that just maybe, perhaps, it wasn’t a good idea to get an adjustable rate mortgage using earnings from the peak of an economic expansion with little to no equity cushion. You see it in gold bugs, who treat the metal like an idol to be worshipped. You see it in people who think a college education is worth any price (it’s not; it’s an investment like any other). You see it in specific businesses like the case study we did of GT Advanced Technologies declaring bankruptcy and wiping out some shareholders who had lost all sense and put most, if not their entire, net worth into it.

Today, you see it most often in index funds, one of my favorite financial market solutions upon which I’ve lavished a lot of praise. I steadfastly maintain that if you are sitting on a 401(k) plan at work, the smartest move, with a few notable exceptions, is almost always going to be to buy a lower cost index fund that is almost entirely passive in its approach. Despite this, you wouldn’t believe some of the messages I get on the topic. Take the recent mail bag response about buying stocks when equity prices are high. In the comments, I happened to mention off-hand that it is foolish for a wealthy investor who has exhausted his or her tax shelter protections to use large amounts of money to buy index funds due to something known as embedded capital gains (and that the risk inherent in doing so is not mitigated by ETFs once you look at the underlying structure despite the advertising line telling people it solves the problem). Precisely for the reasons John Bogle wrote in some of his multi-hundred page books, and in which he openly acknowledges it to be the case, it is often far wiser for a wealthy investor in this situation who wants to follow an index approach to construct his or her own index fund directly by holding the underlying stocks outright in a custody account of some sort. There is no intelligent justification for a taxable investor of significant means taking on a potential, if remote, possibility of being hit with a tax bill while experiencing losses. None. Refusal to acknowledge this fact is simply intellectual laziness.

Judging by some of the messages I received, you’d think I’d have suggested throwing puppies off a bridge. People who do not in any way fit the demographic to whom the problem would apply – you’d need at least several million dollars in a regular, taxable account to worry about this, as well as a decent likelihood of being in an upper tax bracket, which definitely applies to more than a small minority of this community but not the broader general population – thought I was somehow attacking index funds themselves, having ignored everything else I wrote or the context in which the comments were made and the very clear advocation for them within tax shelters and non-profits when the trade-offs in efficiency are worth it and the embedded gains risk is neutralized (many of you know that Aaron and I use them for our family’s charitable foundation due to taking advantage of a donor-advised fund to avoid 990 public disclosures). The fact that I am aware of the inadequacies and might advocate for them anyway, in certain circumstances, doesn’t compute with these folks. In their minds, why would I point out the flaws, including the methodology changes that are quietly happening? They genuinely cannot perceive of a reason a person would otherwise want to know of the shortcomings, let alone publicly discuss them.

Even the objections were evidence that the nature of the problem was misunderstood as the offended had no idea larger investors have entirely different systems and pricing at their disposal. I had one gentleman write, incredulously demanding to know how I could justify paying a broker $7,000 to $10,000 in commissions to purchase 500 stocks. He truly was unaware that 1.) institutional pricing for transactions tends to start at $0.005 per share (half a penny per share), 2.) for a decent-size account, you could almost always negotiate 500 free trades to get it started, and 3.) even if retail rates did apply, they would be both a small overall percentage of the capital base and, unlike an on-going expense ratio, would be amortized over the life of the underlying holdings making them cheaper in the long-run. Another talked about the stupidity of managing 500 different stock positions, apparently, again, unaware that it’s not difficult at an institutional level because there are software programs that create the necessary trade tickets which you then upload to the broker, often in CSV format after the file is auto-generated to make the necessary adjustments to keep your holdings within the parameters you outlined. This is not 1965. You don’t have to get a typewriter, ledger sheet, calculator, and pencil spending hours each month making the necessary modifications as you manually enter trade tickets. In both cases, they were taking what worked for them – small investors to whom the problem did not apply – and trying to scale it to large amounts. I’ve repeatedly told you that you cannot do that; always check your underlying assumptions! The rules are different. The prices are different. The systems are different. The opportunities are different. The pitfalls are different. To repeat what I said earlier, you can’t use the same techniques that build a log cabin and apply them to a skyscraper.

(Interestingly, this seems to manifest itself even in non-investing fields so there’s clearly a mental model of some sort at work. I think the world could be much improved if people occasionally reminded themselves, “Not everything is about me”. I was reading an article in The New York Times earlier in the year; don’t recall the specific piece or author but basically it was about budgeting and personal finance on the cost side. Anyone who pays attention to media demographic knows that the typical reader of the NYT has something like 3x higher household income than the median American household, is substantially richer, enjoys far higher rates of educational attainment and literacy, and is generally much more successful in life. Perhaps more than any other mainstream publication in the country, it is a paper by, and for, the elites. Its readership does not reflect the nation as a whole – not by a long-shot – but rather, the people making the decisions; controlling institutions, exerting influence, overseeing pools of capital, and crafting political policy. Some of the top comments were along the lines of, “I’m a mother making $35,000 a year living in Alabama. What idiot wrote this piece?! This advice isn’t relevant to my life.” The narcissism is incredible. The idea that a relevant article written to a niche audience with clearly defined socioeconomic characteristics must be perfectly tailored to the reader who falls far outside of that group or situational parameters to which it applies would be funny if it weren’t so arrogant.)

How Joe Campbell Found Himself $106,445.56 In Debt to His Broker in a Matter of Minutes Because He Didn’t Understand the Risks of Shorting Stock

An excellent example of the reasons I advocate for being fully aware of risks of each and every investment security, structure, contract, or account type, even if it makes you unpopular, has played out in the financial media over the past twenty-four hours. I first heard about the story from messages sent to me through the contact form (a special hat tip to Scott and Adam, who were the first two make me aware of the story, which allowed me to get the details prior to the GoFundMe page being removed). With the story having now gone viral, it’s possible you already know some of the specifics. In case you don’t, let’s examine the facts.

A few days ago, a guy named Joe Campbell from Gilbert, Arizona had $37,000 in an account at E-Trade. According to some sources, Joseph is a 32-year-old small business owner. It was a speculation account he had segregated from his other funds (an intelligent move, which I applaud). He knew that it was the amount he could lose without harming his standard of living. A company named KaloBios Pharmaceuticals, ticker symbol KBIO, was headed toward liquidation as it could no longer afford to carry on business due to significant cash losses. Campbell went to his broker and borrowed shares of the stock from other investors, promising to return them. He then sold the stock, pocketing the cash. The theory was, the stock would eventually go to around $0, he’d buy it back for next to nothing, replace the borrowed stock, and enjoy the difference. In other words, he shorted the stock. Because he had no offsetting security or derivative that could have protected him if he were wrong in his bet that the stock price would decline, his potential losses were unlimited.

On November 18th, 2015, the stock closed at $2.07 per share. Overnight, an announcement was made that an outside buyer was going to try to acquire the firm and keep it going. The shares skyrocketed – that’s what happens when you have a tiny business without a lot of float and a large percentage of that float sold short so there are people who have to buy it back if the price begins to increase – opening at $14.00 per share. There was little opportunity between $2.07 and $14.00 per share for Campbell to buy back the stock and close out the short position, returning it to the people from whom he borrowed the shares. The stock market is like an auction – you can go from [x] price to [z] price without ever seeing [y] in between. It’s the reason I wince internally when people say something like, “I can always sell on the way down if things go badly”. It’s a significant assumption that the opportunity will be there; an assumption that displays a considerable ignorance about the mechanism through which prices are determined in the equity markets that can come back to harm them when they can least afford it. I don’t like seeing people harmed. I don’t want them to believe things that aren’t true.

When Campbell saw what had happened, he refused to accept it was possible out of some insane notion that his broker was responsible for watching out for him (your stock broker does not have a fiduciary duty to you). Perhaps he might have expected, and maybe even received, more handholding if he were paying 2% trading commissions to a specialist at UBS or Merrill Lynch who was watching over his accounts for him, but he wasn’t. He went for the barebones, self-guided approach and that’s what he got. When he reached a representative of E-Trade, the stock was at $16.00 per share. He told them to close out the position but they couldn’t get their hands on any shares until the price was bid up to an average of $18.50 each.

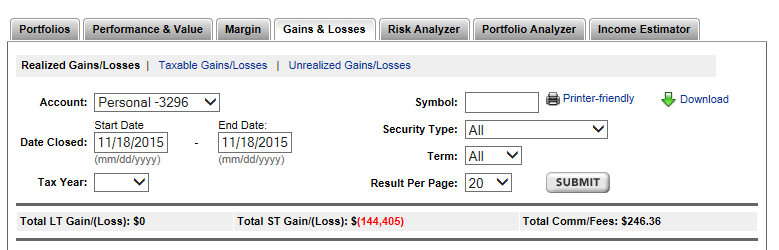

By the time all was said and done, he had a realized loss before taxes of $144,405.31, which he shared in a screenshot:

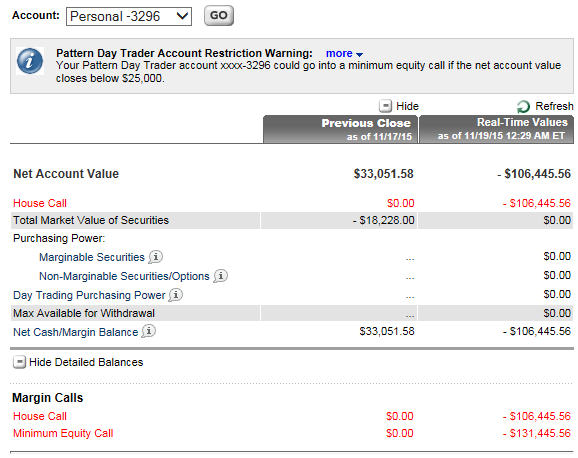

He still owes $106,445.56 after having all of his equity obliterated.

Based on some of his comments, I worry that he doesn’t, quite, understand the situation that he’s facing, even now. This is a real debt, every bit as serious as credit card debt. It will go on his credit report, making it impossible for him to get financing for anything else in his life. Thanks to universal default laws, he will most likely see his insurance rates skyrocket. He might be turned down for jobs in jurisdictions that allow employers to take credit history into account as evidence of character and discipline. The broker can sue him and all but require him to seek bankruptcy protection to make the pain stop. He doesn’t seem to understand the nature of the liability because Campbell says he plans on liquidating his and his wife’s 401(k) – if I were the wife, I would refuse to go along with this as a 401(k) account has unlimited bankruptcy protection, meaning it can probably be salvaged if they otherwise get wiped out (why start from scratch again if you don’t have to do so?) – and then work out an installment plan with the brokerage firm. An installment plan, which, of course, they are under no obligation to provide, this being a demand debt he promised to pay within 72 hours. Short of a miracle, he’s going to default. He broke his word and violated the covenant, taking on risk he could not afford. He still thinks of the broker as a parental figure there to look out for him or work with him when he’s facing hardship. The counterparty is under no obligation to help him pay back the debt or accommodate a repayment schedule. Indeed, they have a duty to the owners they are hired to protect. Perhaps that can be done while easing the stress he and his family face, perhaps not.

Campbell asked for help raising money on GoFundMe, ultimately pulling in $5,310 before ending the campaign. Here is a PDF archive of what happened, in his own words, which was part of the original page he asked everyone to share in the hopes people would kick in a few bucks to bail him out of his predicament. Joe was even willing to share screenshots with the Internet on his donation page (the ones on this page you’ve already seen as documented evidence of the story, which I’m employing under the Fair Use exemption given the public nature of his request for help on a social network), showing the amount he still owed after having all of his equity obliterated.

Should others assist him? I’m torn on the issue and there isn’t much agreement among people when it comes up in conversation. For heaven’s sake, Warren Buffett once allowed his own sister to go bankrupt – literal, total wipeout – from a trade that blew up like this (it involved options) rather than bail her out even though it would have been pocket change to save her the horrendous pain of starting over; a rounding error that couldn’t be spotted on his financial statements if you’d been looking for it. He did it because he thought the brokerage firm should suffer significant losses as they had allowed her to gain much more exposure than was appropriate, assuming that her rich brother would save her if anything happened. He wasn’t going to reward the behavior, even if it meant his sister had to bear the responsibility for her actions. Is that the right way to act? I don’t know.

I do know that, unlike many of the people who commented on the GoFundMe campaign, I’m not inclined to kick the guy when he’s facing this. In fact, I feel sick for him and his wife. If he were a neighbor or a friend, I’d invite them over for dinner, cook them a roast and an apple pie (or whatever else they wanted), tell them it is going to be okay, and send them out the door with arms full of books detailing stories of people who lost far more and ended up going on to major success. I absolutely hate that they are going through this. I’ve spent my entire life working to avoid financial wipeout risk and many of the reasons I write the things I do is because I don’t want you to suffer this kind of catastrophe. There is no reason for it. Making him feel worse or attacking him personally doesn’t undo the damage (though there might be an argument it discourages similar behavior in others). He can, and I hope, will, recover. It will be okay, even if it doesn’t feel like it at the moment. This is especially true given how young and he and his wife are. Mathematically, it is still entirely possible for them to end up wealthy by retirement. If they play their cards right, this is something they can someday look back on and laugh about together.

In any event, Campbell’s losses are far greater than they appear at first glance. Not only is he going to have the emotional stress of dealing with the nightmare, as well as the financial costs of interest, penalties, (potentially) lawyers, higher insurance rates, et cetera, the guy wants to raid his and his wife’s 401(k), which I mentioned earlier. That means paying taxes, losing the tax-deferred compounding, and, because they are younger than 59.5 years old, paying an additional 10% penalty to the IRS. This was a mistake that, depending upon his age, almost assuredly cost him millions of dollars he could have otherwise enjoyed. It happened because he was impatient, entered a transaction he didn’t understand, and happened to be exposed to that transaction when a remote-probability event occurred.

The Moral of the Story

The point of all of this is to remind you that even if everyone around you waives off remote probability events or risks, don’t do the same. (Want to know a secret? Almost everyone around you will waive off remote probability events and risks. Many people don’t like thinking about it. It makes them uncomfortable.) Even if you decide to accept the exposure, anyway, you can at least have the peace of mind of knowing that you’ve done so with full acknowledgment of the downside. You aren’t fooling yourself and that’s important. People who avoid acknowledgment of remote probability risks seem to suffer from the mistaken idea that refusal to acknowledge them means they aren’t present. Nothing could be further from the truth. The nature of the risk hasn’t changed – it’s always there – you’re simply aware of it and can decide to accept it, reject it, or take countermeasures to mitigate it.

Again, I think there’s something neurological going on with a lot of folks who fall into this trap as it manifests itself in too many places. You see men and women who know their spouse is having an affair but as long as it isn’t explicitly stated, they can go on with their lives as if it isn’t real. You see people who know their child is a drug addict but as long as it isn’t explicitly stated, they can pretend it isn’t a problem. You see people who know an employee is stealing from them but they don’t want to believe it so they refuse to confirm their suspicions. It’s related to, but different from, Mokita. Do not tolerate this kind of intellectual laziness and emotional frailty. You cannot fix a problem without identifying the problem. Avoidance only makes things worse. Never be afraid of facts. Interpret them, incorporate them, set them aside as not relevant to your situation, but never fear them. Facts, in other words, should never offend you.

On that note, none of us are guaranteed a happy outcome in life. Sometimes, things just suck. The best you can do is conduct your family’s affairs in a way that tilts the odds in your, and their, favor. That includes:

- Collecting cash generating assets

- Avoiding liabilities (contingent and explicit)

- Sticking to what you know and understand

- Keeping your costs reasonable

- Identifying and nurturing your core economic engine

- Intelligently taking advantage of tax efficiency

- Arranging all of this to serve your own personal needs, whatever those might be. Money exists to make your life better. You do not exist to serve it. It’s a tool; nothing more, nothing less.

All of this could have been avoided if Campbell had focused on risk exposure. What were the odds something like this happened, let alone during the tiny window during which he had short exposure? Miniscule. Nevertheless, since the downside threatened to destroy his standard of living, he should have walked away from the transaction. Avoiding bad deals is just as important as finding good ones.

Do not accept “it’s not likely to happen” as the end of the conversation. Always follow up with, “Yeah, but what if it does?”. I don’t care if you’re an engineer working on a construction project, a portfolio manager building an asset allocation, or an executive at a pharmaceutical company facing clinical trials for a promising drug. If merely discussing bad outcomes causes you distress or fear, you need to get control of your emotions. Perhaps you have no defenses against a particular bad outcome. Know that. Own it. Take responsibility for it. Right now, Joe Campbell is at the mercy of his broker, to whom he is significantly indebted. I don’t ever want you to find yourself in a situation where you have to depend on the kindness of others to keep food on the table. I want you to be financially independent so you can spend the 27,375 days you’ve likely been granted doing what it is you enjoy.

I don’t tell you this stuff to scare you, I tell you this stuff to empower you so you can make decisions – fully-informed decisions – about what you’re willing to accept in terms of trade-off without having to rely on others. As long as I write, I will never do you the disservice, or show you the disrespect, to shield you from the world as it is. There are no silver bullets. There are no magic beans. You must learn to think, analyze, and arrange in ways that optimize your output and upside/downside exposures. This isn’t limited to your portfolio, but rather a philosophy that should permeate your personal life and career.