November Is for Buying More Nestlé Shares (… at least for the Kennon-Green Family)

It’s been a long time since I’ve talked really about Nestlé SA other than mentioning it in passing last week. It’s on my mind because this morning, I had my parents acquire some more in their personal portfolios, which I intend for them to hold for the remainder of their lives (which, unless something changes, should be at least another 30 years, God willing, as they are both in their early-to-mid 50s). It’s not much, just a bit of cash that had built up and needed to be put to use, but it adds to the collection of ownership in Switzerland’s most famous food company that they, Aaron and I, and nearly everyone else in our lives have have been acquiring over the years. Here and there, bit by bit, buying whenever the price is reasonable as it is one of the few businesses that we consideris worthy of a home in the permanent portfolio.

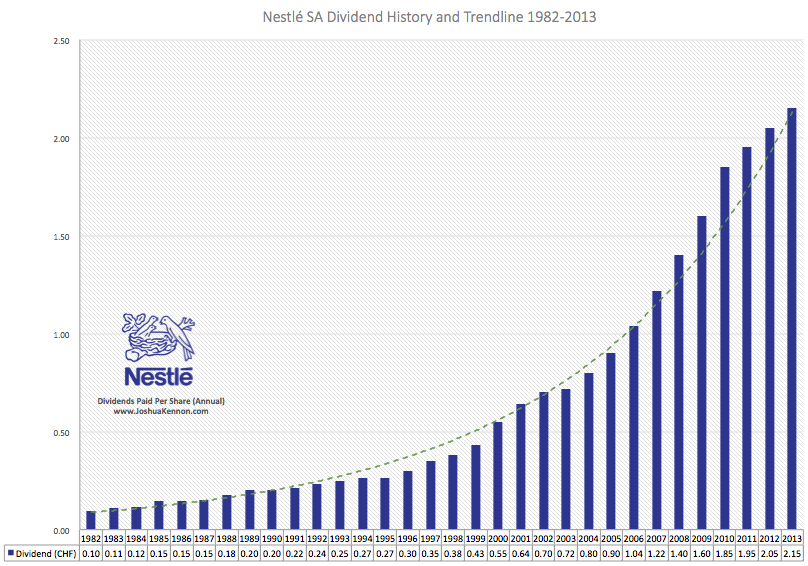

The dividend will be coming up in five or six months and, like almost every year for the past few decades, I expect we’ll see another comfortable raise as the board of directors passes on the profits from chocolate, coffee, ice cream, tea, water, infant formula, cereal, powdered milk, pasta, frozen dinners, nutritional supplements, and pet food. Look at the dividends (which do a nice job of tracking the trajectory of earnings for the underlying earnings in this case) in my lifetime alone. It’s a glorious sight to behold. There are multiple recessions, bank collapses, wars, oil shocks, Presidential administrations, technological revolutions, interest rate environments, and real estate bubbles in there, yet the Swiss Francs keep on getting sent out to owners. Some years the shares are up, some years the shares are down, but over time, owners make more and more money, which is eventually reflected in total return.

Of course, dividends alone are somewhat meaningless because what counts is total return. What does that total return look like? Prepare yourself. You’re about to enter the realm of investor nirvana.

A quick, back-of-the-envelope assessment shows that someone who bought 1 registered share the year I was born would have paid the split-adjusted equivalent of 2.30 CHF per share. That share is now worth 70.90 CHF, or 30.82 times what he paid for it. On top of that, the share has collected aggregate cash dividends of 21.60 CHF. This puts the total ending value at 92.50 CHF for every 2.30 CHF invested, a 40.22-fold pre-tax gain, assuming no dividend reinvestment. Had you plowed those dividends back in for more ownership along the way, you’d have made a lot of extra money.

I’ve said it before but it bears repeating: Despite these incredible results, you rarely hear people talking about Nestlé at cocktail parties. It’s never the hot stock tip hyperactive twenty-something-year-old recruits to the financial marketing machines of Wall Street tout to their clients. It isn’t the subject of magazine covers or dramatic corporate biographies the way exciting new technology firms routinely are. It isn’t the sort of company that makes people raise money and put a big chunk of their life savings to work. I suspect part of the reason is it is too simple. How would a broker put food on the table if he were to tell clients, “Let’s buy some more Nestlé and forget about it for the next 50 years?” even though that would be the best advice he could give to a lot of families, in my opinion, under present conditions and pricing.

To visualize how we, and we imagine all the other Nestlé stockholders feel about this chart, requires me to use my limited Photoshop skills …

Want some tasty DiGiorno pizza? How about a Butterfinger? Some Häagen-Dazs? Maybe some sparkling water? We have Perrier and San Pelligrino so take your pick. Some Gerber baby food for your little bundle of joy? Some Friskies for your cat? Chocolate? We have lots of delicious chocolate. You want some chocolate I can tell. Maybe some Toll House cookies? Some cocoa? Some cereal?

How about some cosmetics, perfume, hair dye, shampoo, conditioner, or nail polish? Nestle owns 23.29% of the shares of the nearly €70 billion publicly traded French beauty giant L’Oréal. Whenever you hear the jingle for “Maybe it’s Maybelline” you should change the lyrics to, “Maybe it’s mah monies”.

If I had to guess, I’d hope we see a cash dividend increase to at least 2.25 CHF per share when the Spring dividend day arrives. If that turns out to be accurate, and the shares at 70.90 CHF each as of this morning, it would indicate a pre-tax dividend yield of 3.2% per annum. Some analysts appear to be expecting more, which is fine by me. It partly depends upon how the board wants to return cash. There was an $8 billion share repurchase program that is supposed to be completed this year so they may want to reduce shares outstanding as a higher priority. Nestlé unloaded the guns and did long-term owners an incredible service by reducing total shares outstanding 11.78% in the years surrounding and following the Great Recession. That means each share of Nestlé since 2008 actually represents an extra 13.35% worth of equity.

General Thoughts on Nestlé Since It’s Been a Long Time Since We Last Discussed It

There’s a saying in the money management world that Nestlé is the “get rich slowly” company. As Warren Ackerman, an analyst at Société Générale put it, “The old adage – when the going gets tough, the tough buy Nestlé” is equally as applicable.

This is not a business to trade. This is not a business in which to speculate. This is one of those rare gems of a company that you buy, hold onto for life, and pass on to your children and grandchildren (though some successful value investors do “trade at the margins”, meaning they are so familiar with its core businesses that they will tilt their portfolio to buy more when it seems undervalued and trim the position when it seems overvalued, retaining a core position that serves as a base; something most folks who are not professionals and who are not regularly examining the operating results should probably avoid). You pay a one-time commission and then have a near $0 expense ratio (unless you opt to invest through the ADR, in which case you’ll pay a somewhat inconsequential fee to the sponsoring bank for converting your Swiss Franc dividends into U.S. dollars). Like an oak tree, Nestlé has grown bigger, richer, and stronger over the years, rewarding its owners. Even the dividend is paid out only once per year, as a family partnership might do.

This is not a business to trade. This is not a business in which to speculate. This is one of those rare gems of a company that you buy, hold onto for life, and pass on to your children and grandchildren (though some successful value investors do “trade at the margins”, meaning they are so familiar with its core businesses that they will tilt their portfolio to buy more when it seems undervalued and trim the position when it seems overvalued, retaining a core position that serves as a base; something most folks who are not professionals and who are not regularly examining the operating results should probably avoid). You pay a one-time commission and then have a near $0 expense ratio (unless you opt to invest through the ADR, in which case you’ll pay a somewhat inconsequential fee to the sponsoring bank for converting your Swiss Franc dividends into U.S. dollars). Like an oak tree, Nestlé has grown bigger, richer, and stronger over the years, rewarding its owners. Even the dividend is paid out only once per year, as a family partnership might do.

The recipe is simple: Management tends to raise prices by at least inflation, buys back some shares to increase EPS when the stock is undervalued, and adds a little organic growth through new product launches and acquisitions. It also has a lot of capital allocation discipline. For example, when the former Kraft Foods (it has since split into two different companies) sold its pizza business under incredibly stupid tax terms only to turn around and buy a chocolate business at a much higher price, drawing the ire of Berkshire Hathaway, the largest stockholder at the time, it was Nestlé that stepped up with the checkbook and effectively said, “Yes, we’ll buy those boring, highly profitable, slow growth pizza businesses you think are so beneath you so you can chase after high-profile, prestigious acquisitions to the detriment of your stockholders.” Management knows that growth only matters if it makes owners richer. As a matter of policy, it maintains one of the strongest balance sheets in the world and generates double-digit returns on capital. There is a reason it is a cornerstone of a lot of European index funds.

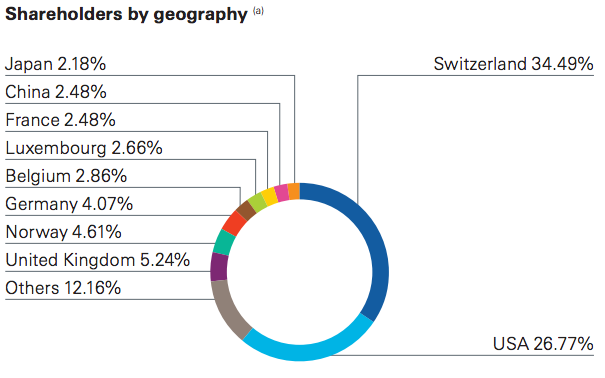

On that note, it’s not just Europeans who own Nestlé. Even though it isn’t a component of the major indices in the United States – despite its roughly quarter-of-a-trillion dollar market capitalization (yes, trillion with a “t”), it is not part of the Dow Jones Industrial Average nor the S&P 500 – a lot of Americans count it among their core holdings. Take a look at shareholders by geography at the end of the last fiscal year:

Given that Aaron and I modified our investment policy manual to treat Nestlé not as a stock, but as a private business that we hang on to as tenaciously as we do our operating companies, the key is to avoid paying too much. Once shares are on our personal family books, generally, we don’t envision them coming off again except under extraordinary circumstances. That means the opportunity cost of locking up the funds is high.

The good news? Overpaying doesn’t seem to be a problem at the moment no matter how you analyze the financial statements. If we think about Nestlé as a private business, it’s selling for around 15% under its intrinsic value for someone who had a long-term horizon and wanted to live entirely off the underlying profits of the enterprise even if the stock exchange were closed. That’s not a screaming bargain, but for what we’re getting, we’re happy with it. (To grossly oversimplify and avoid diving into complex discounted cash flow discussions, I wouldn’t want to pay more than twice the sum of the projected dividend yield + the projected 5-year growth rate in EPS (e.g., if the dividend were 3.2% and 5-year growth estimates were 7.5%, I wouldn’t want to pay more than 21.4 times earnings). In most cases, throughout most of the company’s history, that yardstick has been a sufficient enough gauge to do well. This is because the quality of the businesses is high enough there isn’t a sustained, huge disconnect between reported profits and true owner earnings (though, at the moment, reported profits are under-reflective of actual economic earning capacity). I wouldn’t be using the same metric to value a steel plant, telecom firm, or oil pipeline.)

I suspect a lot of inexperienced investors overlook Nestlé because they aren’t used to foreign currency adjustments or don’t know how to research international firms. In the past nine months, by way of illustration, it looks like sales have fallen by 7.5% but organic growth was so good, they were actually up by 4.5% despite a fairly challenging consumer environment. It’s just that the financial statements are reported in Swiss Francs and the CHF has appreciated considerably against many global currencies. As Nestlé makes a lot of money outside of Switzerland, the accounting figures take a hit but the money, in most cases, is still being used in their respective nations to build new factories and buy up competitors. Likewise, the ADS that trade in the United States, representing the foreign Swiss shares, are often incorrectly listed. Go take a look at Yahoo Finance’s website and it shows no dividend at all and a p/e ratio that doesn’t much reflect economic reality! It makes the stock look far more expensive than it is if you’re talking about 10, 20, 25+ years of ownership.

Maybe all this noise is one of the reasons the shareholder base tends to weed out the novice when, paradoxically, it is precisely the sort of enterprise that should hold the most appeal. Nestlé never looks like it’s going to be the best stock to own over the next 12 months. Ironically, it has almost always been one of the best stocks to own over the next 12 years. Life is funny that way. Of course that could change in the future – there are no guarantees in life or common stock investing – but it’s worse observing and noting.

Image Credit: kenary820 / Shutterstock.com