You Cannot Understand the Rise of Wealth Inequality Without Acknowledging the Role of Interest Rates

In August of 2014, I wrote a post called Lies, Damn Lies, and Statistics. I penned it because, at the time, I was seeing a lot of situations in the media in which data was being used to push a political agenda on either the far right or the far left. I have no problem with people passionately advocating for changes in which they believe – say, for example, that the minimum wage should be increased or that education funding should not be tied to local property taxes – but I have a real problem when advocates for a given proposal lie by manipulating data in a way that is not truly representative of what is happening. I don’t think it’s good for civilization in the long-run. I want as many people as possible to understand complex topics. That way, honest disagreements are based upon genuine policy and goal differences, not misunderstandings or ignorance.

I find myself especially dissatisfied with data manipulation when it is for something that I believe is important. Over the past few years, I’ve written quite a bit about inequality and the forces driving it. It’s a topic that is close to my heart. Aaron and I were first-generation college graduates. We had to pay our own way through school, received no inheritances or trust funds, paid our own rent, and became self-made members of the top 1% by systematically studying how other people did it then putting those lessons to work in our own lives. We pieced together our estate decision-by-decision, day-by-day, creating and acquiring things that produced cash and that we believed made sense. It is important to us that the ladders of upward mobility remain in place behind us for others who are just as talented, just as hard working, but who may have been born into circumstances where they didn’t have a lot of family capital to get them started. A personal example: in my own life story, as many of you know, the single most important tool I had at my disposal and that is responsible for getting me where I am today was the public library. I love the library. I love the entire concept of the library. My gratitude is so deep that I consider it a moral obligation to help others by sharing some of the knowledge and information I pick up throughout my own experience; to pay it forward so that those who come after me can have better lives, achieve financial independence, and be more fulfilled.

That is one of the reasons that I want to take a few moments out of my day and point out a concept I keep seeing pop up – a lie cloaked as a half-truth that is meant to cause the person reading it or hearing it to falsely conclude that the sole or primary root cause of rising inequality was a specific administration or law. Namely, it goes something like this. You may have encountered it already in your own reading or day-to-day conversations: “Since Ronald Reagan became President, wealth inequality has skyrocketed and most Americans are getting screwed by the wealthy.” Alternatively, Reagan himself may not be mentioned but, instead, a general time period around the years when he became President are used as a starting point to discuss wealth inequality.

The time period selected is not an accident. It is purposeful and calculated. A major part of the picture is being intentionally obscured from your vision by those who have a political agenda. To explain how, I’d like to look at another major cause of rising inequality, namely the function of interest rates in asset valuation. Before I do, I want to address several things:

- What I am about to discuss is not the sole or primary cause of wealth inequality but it does play an enormous part.

- Automation and globalization are also responsible for a substantial portion of wealth inequality.

- Human nature and the natural love and affection one has for their own children also has played a role in increasing inequality as the top 20% behaves in perfectly rational ways that support their own family advantages, creating self-reinforcing cycles of success that have begun to cause system-wide consequences.

- In the long-run, wealth inequality can be bad for society if it extends to political inequality; if a small cadre of the wealthy conspire to hijack the political system and vote themselves ever-increasing and insurmountable advantages, such as those that make it harder for people to compete in a truly free and well-regulated market, it can break capitalism, which is the greatest system for increasing the standard of living for the poor and middle class that humanity has ever invented. Nothing else has ever come even remotely close. Therefore, anybody who cares about the long-term health and safety of the country, and about his or her fellow citizen, should be concerned about wealth inequality to at least some extent. The system needs to work for all Americans, not just a minority of Americans. This is why you sometimes see me write about my desire to smash a lot of the S&P 500 companies into much smaller businesses. Too few companies have too great an influence in the day-to-day lives of the typical person.

Now, let’s get into the details.

The Role of Interest Rates in Asset Valuation

Asset prices are heavily influenced by the general level of interest rates in a particular economy at a specific time. Think about real estate. When buying and selling productive property, return potential is often expressed in the form of a “cap rate”, which is short for “capitalization rate”. The cap rate figure is essentially a way to estimate what the property might produce if you bought it on a 100% cash basis (no debt) and collected the income. It is calculated by taking net operating income per annum and dividing it into the purchase price. That is, if you had a property that produced $1,000,000 in net operating income per annum and you bought it for:

- $5,000,000 in cash, your cap rate would be 20%;

- $10,000,000 in cash, your cap rate would be 10%;

- $20,000,000 in cash, your cap rate would be 5%.

The higher the price you pay for a property relative to net operating income, the lower your return. The lower the price you pay for a property relative to net operating income, the higher your return.

I say cap rate is an estimate because cash flows are not entirely predictable – rents can and do decline – but just as often, real estate developers and investors who are particularly intelligent, disciplined, and talented find ways to increase profits by improving the productivity of a given property, making their actual returns higher, sometimes materially higher, than the cap rate advertised by the seller when the property was on the market. Like an entrepreneurial business, the value of real estate can differ greatly depending upon the hands in which it resides. Not everyone is equal in terms of converting a property’s potential into its best, most productive use.

Real estate cap rates are a function of multiple inputs but among the most important is the level of the so-called “risk-free” interest rate that serves as an opportunity cost benchmark for all investment assets. For much of the past century, the global risk-free rate has been the U.S. Treasury bill, note, and/or bond, backed by the full taxing and military power of the United States Government. That is, a rational investor will look to the T-Bill and say, “If I do nothing but sit on my porch all day reading a book and drinking a coffee, I can earn [x%] return with little to no short-term risk. Therefore, any project I undertake must compensate me well above and beyond this risk-free rate, otherwise it isn’t worth the effort and potential loss of wealth.”

The mathematical consequence:

- When the risk-free rate is lower, people will settle for much lower returns on investment. This means asset prices must rise relative to net operating income.

- When the risk-free rate is higher, people will demand much higher returns on investment. This means asset prices must decline relative to net operating income.

Read those items again. Never forget these are inversely correlated. I’ll repeat it:

- Lower interest rates = higher asset prices

- Higher interest rates = lower asset prices

To illustrate, imagine the risk-free rate were 10%. Under such circumstances, a real estate investor might demand a 15% cap rate to justify an investment. After all, the 10% rate is not only the safest short-term yield, it is also exempt from State and Local income taxes, giving it a further advantage. If, on the other hand, the risk-free rate were 2%, a real estate investor might demand cap rates of only 5% or 8%. The more desirable the property, the lower the cap rate as people are willing to pay more to own it. There exists a tipping point at which interest rates become so low that people forget the situation is likely temporary and they do incredibly stupid things in pursuit of yield, such as buy 50-year or 100-year maturity bonds. This is a major trap. Do not fall into it! It is often better to earn little to nothing on your money, even for many years, than it is to tie it up in a sub-par investment.

This same phenomenon – asset prices moving in an inverse correlation to the risk-free rate – applies in all other productive asset classes, as well; business ownership (both privately owned businesses and publicly traded equities), intellectual property rights, fixed-income securities, you name it. Each asset class has its own vernacular for explaining the relationship. For example, when talking about stocks, analysts may refer to the “equity risk premium”, which is the spread of a company’s base earnings yield (the inverse of the price-to-earnings ratio) over the risk-free rate, comparing it to historical levels.

Over much of the past century, U.S. stocks have boasted an equity risk premium that tends to float in the 3.5% to 5.5% range. As fear or greed grips the stock market, the equity risk premium may fall far outside of these bounds, even for extended periods of time. However, mean reversion tends to take over and that has seemed to be the sweet spot. To provide another simplified example, if the risk-free rate were 8% during a given period, and equity risk premiums were in the typical historical range, investors would want 11.5% to 13.5% earnings yields on their stocks, which means the p/e ratio of the typical company might range between a high of 8.7x earnings to a low of 7.4x earnings. If the risk-free rate were 2% under similar circumstances, investors might demand earnings yields of 5.5% to 7.5%, which would translate into typical p/e ratios ranging from a high of 18.18x earnings to a low of 13.33x earnings.

As with real estate, the actual risk premium for any given business will depend upon the specifics of that company – people may still be happy to pay rich valuations for highly promising enterprises even in a high interest rate environment – but interest rates act on asset values the same way gravity acts on mass; constantly exerting pull as things move around their general level. It’s also important to note that the earnings yield is likely to be based upon normalized earnings, not the earnings in any specific year. A company might appear to be trading at 3x earnings or 40x earnings but really be at, say, 16x its usual earning power with noise in the one-year figures due to a one-time restructuring charge or a windfall profit.

A Hypothetical Example of How Interest Rates Can Influence First-Glance Wealth Inequality

Again, I’m going to need to oversimplify some things but the point is to demonstrate how powerful interest rates can be in determining asset prices.

Let’s imagine you live in a prosperous suburb. Your best friend lives next door. To keep this straightforward, we’ll focus solely on investment assets and not personal assets such as home equity. Your entire investment portfolio consists of an apartment building that generates $500,000 per year in net operating profit. Your best friend’s entire investment portfolio consists of $250,000 in certificates of deposit with maturities of 3 to 5 years.

Now, further imagine two scenarios.

Scenario A: The risk-free rate is 2% and the cap rate for comparable apartment buildings is 6.5%. This means your apartment building is valued at $7,692,308. You still collect $500,000 in annual income from it. Your friend earns 2% on his or her CDs because, in this fictional scenario, term bank deposits are yielding right around the risk-free rate. That equals $5,000 in per annum income (though, unlike the actual risk-free rate, this income would not be exempt from state and local income taxes). The inequality figures are:

- You earn 100x the income your friend earns

- You have 30.8x the net worth your friend has

Scenario B: Nothing has changed except several years have passed. Now, the risk-free rate is 8%. This means the cap rate for comparable apartment buildings is 12.5%. This means your apartment building is valued at $4,000,000. You still collect $500,000 in annual income from it. Your friend earns 8% on his or her CDs, or $20,000 in per annum income. The inequality figures are:

- You earn 25x the income your friend earns

- You have 16x the net worth your friend has

Note that little has changed for you under either scenario. Yet, someone could write a news story in this situation saying that “wealth inequality has plummeted by 75% and income inequality has been nearly cut in half!”. It doesn’t mean much because you own the same building. You have the same number of renters. Your household income is the same. The biggest difference is that, under Scenario A, if you were inclined to sell, you could convert your productive asset into a higher amount of cash. However, with the price level of all other assets also elevated, any deployment you make would be unlikely to increase your income, particularly after factoring in the capital gains taxes that might be owed on the sale. There are ways around this – e.g., Congress has sanctioned things like the widely-used 1031-exchange – but that means you’d need to remain committed to the real estate asset class. (It’s important to note that intelligent investors are often willing to pay capital gains taxes as trying to avoid them at all costs can lead to a lot of misery and suffering. For example, prior to the real estate market collapse between 2007 and 2009, the financial world was filled with early warning signs such as shrewd real estate investors and developers showing up to private banks and wealth management firms with piles of money, requesting the cash be parked in bonds. These investors had cashed out of their holdings, sold their homes, and moved into apartments because they felt like pricing had become deranged. Billionaire Charlie Munger talks about how one of his friends sold half of his investment property portfolio and used the proceeds to pay off the debt on the remaining properties, ultimately allowing the investor to sleep soundly through the worst real estate market in generations.) On another note, it should be mentioned that long periods of elevated asset prices can create distortions that later grow into major problems. For example, you may decide to cash out some of your equity by borrowing against the apartment value when it is at $7,692,308, introducing more leverage into the system.

In this suburb, wealth inequality and income inequality are both going to plummet and rise depending upon what happens with interest rates even if nothing else changes.

Got it so far? Okay, great. Let’s look at the history of the risk-free rate over the past few decades.

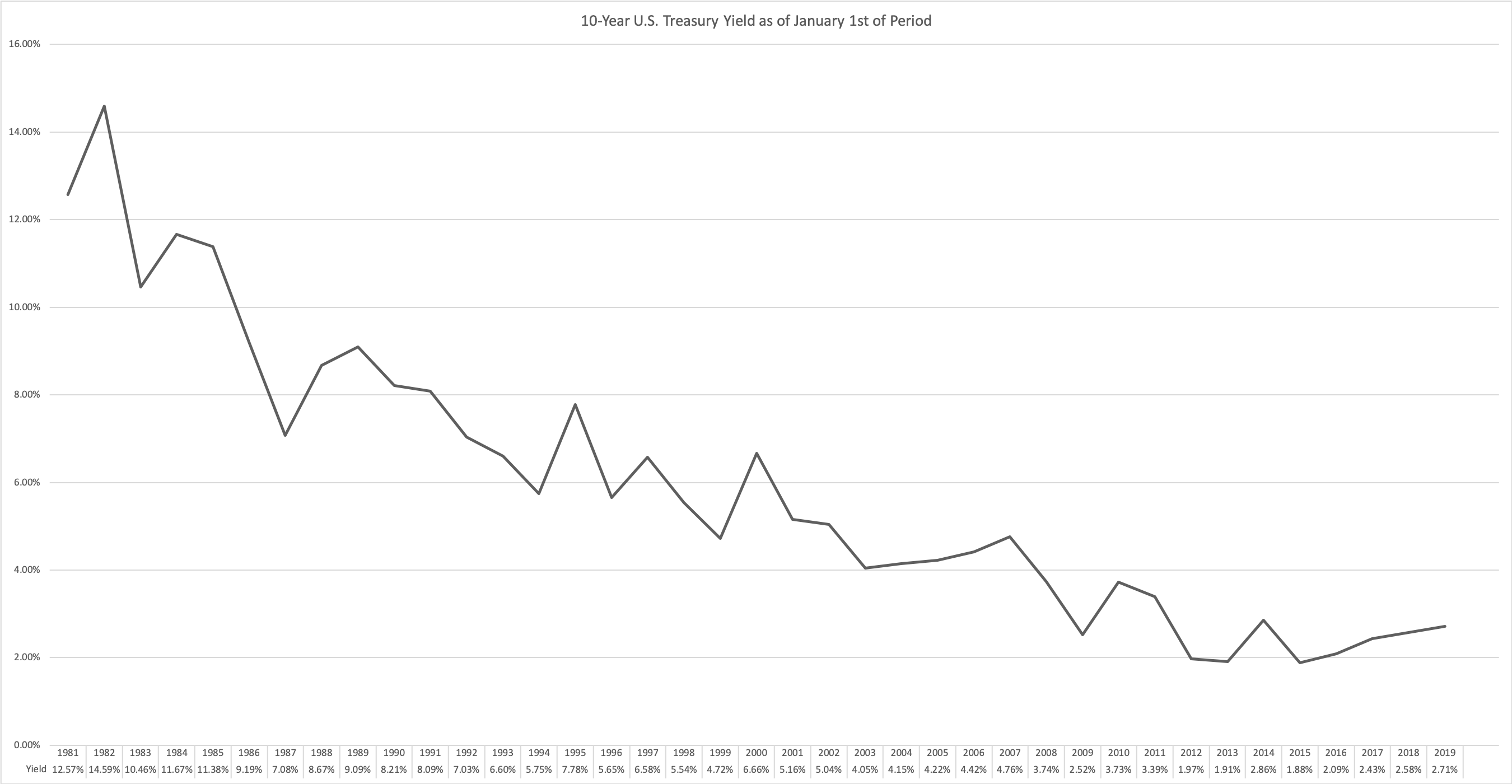

A Look at the 10-Year Treasury Yield from 1981-2019

For our risk-free rate, we’ll use the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield during January of each year from 1981 through 2019 because it will serve our purposes and was the easiest data set for me to grab. It’s somewhat approximate because I don’t want to have to code in hundreds of individual figures but the end result is right on the money and demonstrates the point nicely. I’m willing to deal with that imprecision to highlight the phenomenon.

Ronald Reagan took office in January of 1981. Take a look at where interest rates were at the time:

Sources: U.S. Treasury Department and Robert Shiller’s book Irrational Exuberance

You are reading that correctly: 12.57%. (The situation was so bad that mortgage rates reached 18.5% for many homeowners seeking to finance a property.) The next January, the risk-free rate climbed even higher to 14.59%. Thereafter, it continued a bumpy, yet ultimately-downward decline, hitting a low of 1.88% back in 2015. Again, keep in mind this data set looks only at the 10-year yield as of the beginning of January of each year. There were a lot more fluctuations throughout each of these periods but this gives you the big, overall trend line.

Given what you just learned about asset values and the inverse relationship to interest rates, two points should be immediately obvious:

- A not-insignificant portion of the increase in wealth inequality over the 1981-2019 period is a by-product of the fact the beginning of that measurement period represented some of the highest interest rates in American history, while the latter part of that measurement period represented some of the lowest interest rates in American history.

- The nosebleed rates came as Paul Volker at the Federal Reserve sought to tame the raging inflation of the late 1970s and early 1980s which, combined with high unemployment, led to a phenomenon known as “stagflation”. The so-called “misery index”, created by economist Arthur Okun and calculated by combining the inflation rate with the unemployment rate, began to climb during President Nixon’s administration (1969-1974), hitting a high of 13.61. It continued its upward rise to 19.9 during President Ford’s administration (1974-1977). Later, during President Carter’s administration (1977-1981), it reached an unthinkable 21.98. When President Reagan took over in 1981, he saw it tip out at 19.33 before it collapsed to a low of 7.7 in December of 1986 as both inflation fell off a cliff and people found jobs, leading to what has been referred to as “The American Miracle”. The trajectory of this improvement played a huge role in Reagan’s total dominance of the electoral college and popular vote during his 1984 re-election campaign as he captured the entire country, coast-to-coast, with the exception of Washington, D.C. and Minnesota. Reagan ended up with 525 electoral votes, humiliating Mondale, his Democratic opponent, who won only 13. Reagan won the popular vote by 54,455,000 compared to Mondale’s 37,577,000. It was a crushing landslide unlike any seen in the modern political era. Those numbers say it all. It is truly difficult to overstate Reagan’s popularity with the average American family during this period. You cannot understand the political reality of this period without understanding how beloved he was. His opponents referred to him as “The Teflon President” because he was so adored that no negative news or scandals seemed to stick to him.

- The record low risk-free rates materialized due to decisions made during the 2007-2009 collapse when the Federal Reserve, Congressional Democrats, and former Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama came together to save the entire global financial system from a cataclysmic meltdown that would have rivaled, if not exceeded, the Great Depression. The quantitative easing that kept this entire system afloat – and, it should be pointed out, ended up generating a profit to taxpayers – caused asset values to decline far less than they would have otherwise declined, and then, upon recovery, rise much further than they otherwise would have risen, avoiding a painful, perhaps multi-decade, liquidation.

- When and if the system returns to a normalized interest rate environment, many metrics of inequality, namely those tied to net worth, will appear far less extreme when expressed as a multiple to median than they are presently. For example, if we found ourselves in an interest rate environment like 1995, the collective net worth of billionaires on the Forbes 400 list would be materially lower at current earning levels despite these men and women owning the same companies.

It should also be pointed out that other metrics of inequality will not be affected too much by a change of interest rates and, I expect, will still remain much higher than they were in 1981. For example, a rise in interest rates may not cause a decline in the ratio between CEO pay and the pay of a company’s median worker (unless higher interest rates lead to lower corporate profits, and thus executive compensation), because the primary cause of the disconnect is a non-related structural issue. Companies have been consolidating for decades, leading to a situation in which many industries reflect a winner-take-all setup; where two to five companies control nearly the entire market. Government regulators have been far less willing than they were in the past to smash these companies apart to spur competition, leading to the outcome. In some cases, such as banking, government regulation is a major reason for the consolidation and bears a major portion of the blame. Take a look at the banking industry. It is not an accident the banks have been consolidating when you consider:

- Congress removed inter-state merger limitations on banks, allowing them to go on acquisition sprees;

- Congress removed restrictions forbidding commercial banks (those that make traditional bank loans and take deposits) and investment banks (those that help companies raise capital by issuing stocks and bonds to the public markets) from being part of the same enterprise;

- Congress continually raised compliance costs and requirements to the point that any bank that was not a mega-institution faced a material cost disadvantage compared to banks with hundreds of billions, or even trillions, of dollars on deposit.

A smaller bank with $1 billion in deposits can’t exactly go around offering executive compensation packages of $10 million to $25 million per annum all the time. A bank with $1+ trillion in deposits can. In fact, the bigger bank has every incentive to pay the highest price it can for talent given the greater complexity of the organization. Like sports teams fighting over superstars, getting it right matters much more than a few extra million in pay each year when that is a rounding error to your income.

To give an example from our own portfolio, Aaron and I have a substantial weighting in shares of The Walt Disney Company. I consider Bob Iger one of the greatest media CEOs in history. If he would continue running the business for the next ten years, rather than retiring, I’d gladly vote to pay him $150 million a year. He’d be worth every penny. That pay would be so inconsequential to the value I believe he’d add in the top job, I think any owner would be deranged to vote against it. He has demonstrated, time and time again, that every $1 of retained earnings entrusted into his care has been turned into more than $1 of intrinsic value. He’s overseen the creation of multi-generational intellectual property that should pump out cash for a long, long time. Frankly, if Iger were to approach investors and say he wanted to spend all of Disney’s profits for the next three years building out a streaming service to compete with Netflix, I’d happily forego earnings for that 36 month period and take the risk. I can’t say that about a lot of other corporate leaders.

Why This Should Matter to You as a Citizen and a Voter

When trying to tackle complex issues like wealth inequality, your judgment is going to be substantially improved by understanding the underlying causes. Politicians who are loudly proposing large, society-wide overhauls of taxation, social safety nets, and other programs, many of which would expand the power of bureaucrats and party insiders, without acknowledging that the increase in wealth inequality since 1981 is actually less extreme than it first appears when you adjust for cyclical economic forces such as the interest rate environment – and, thus, likely to mitigate somewhat as interest rates normalize in the coming years – are displaying either their mendacity, which means they shouldn’t be trusted, or their ignorance, which means they aren’t qualified to have an opinion. This situation persists because over and over again, voters have demonstrated that they reward politicians who lie to them; who cater to their base prejudices and tell them what they want to hear, not what is actually happening. They want to feel good, not find solutions.

More than anything, I want to give you an appreciation for the fact that interest rates matter. They matter to your personal net worth. They matter to household inequality. They matter to government discretionary spending. They influence nearly everything in your life. Studying how interest rates have historically interacted with various assets, liabilities, and business models is a wonderful use of your time if you want to find ways to help reduce risk and structure your financial life more intelligently. How would you and your family be helped or harmed if interest rates rose substantially? How would you or your family be helped or harmed if interest rates declined substantially? You should know the answer to those questions; to know the interest rate sensitivity of your balance sheet and income statement.

In the coming years, one of the big stories that will unfold is how we unwind ourselves from historically low interest rates and return to a normalized environment. There is no playbook for this and the stakes are higher than most folks realize. For the individual investor, owning a diversified collection of wonderful businesses that produce a lot of cash and that have some sort of built-in inflationary and deflationary defense mechanism has proven the most intelligent way to behave despite year-to-year fluctuations in quoted market value. The best of these businesses can actually profit from inflationary periods of rising prices and interest rates because they are able to generate earnings without a lot of capital expenditures, meaning they have the benefit of increasing prices without the drawback of needing to fund more property, plant, and equipment. For example, consider a widely-owned business such as Hershey, which has been a member of the S&P 500 since the introduction of the index back in 1957. Hershey can raise prices in inflationary environments and, at least historically, has still managed to remain highly profitable even during periods of severe economic stress when prices are declining. This dual power arises from the fact that 1.) its returns on tangible capital are extremely high and 2.) even those who are broke, and losing their home, will still reach into their pockets and spare a couple of bucks to enjoy a Hershey’s bar or Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups for a moment of enjoyment in the midst of otherwise dark times. It doesn’t mean Hershey’s stock won’t decline by 50% or more from time-to-time – it has and, I believe, will continue to do so as long as its shares are publicly traded – only that for the investor who thinks like a long-term owner, and who has no intention of selling his or her shares except, perhaps, to opportunistically buy or sell around the margins of intrinsic value based upon the other opportunities on his or her desk, the core economic engine has a lot of appeal relative to many other enterprises present known factors considered.

Aaron and I spend a lot of time trying to identify such businesses. It’s one of my favorite things to do. Combined with our frugality and propensity to save, it becomes a self-reinforcing, virtuous cycle of upward prosperity as the compounding engine we’ve developed takes on a life of its own, ever-expanding as dividends and interest are generated and become available for redeployment. There is nothing else I would rather be doing.

Again, this post is not intended to take away from our past conversations. As a country, we face significant challenges, which include the very real, and very painful, decline in low-skill wages that has manifested as the middle class divided into “has” and “has beens” – e.g., as Jake Sullivan, senior policy adviser to Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign, national security advisor to Vice President Joe Biden, and director of policy planning at the U.S. Department of State during the Obama administration pointed out in an article called The New Old Democrats in the Fall 2018 edition of Democracy: A Journal of Ideas, “Since 1971, the percentage of both upper-income and lower-income households in this country has increased, hollowing out the middle class from 61 percent to below 50 percent of all households. Meanwhile, the share of aggregate income going to middle-income households fell by roughly a third in that same period.” This inequality is only growing worse because successful people tend to fall in love and marry each other, establishing super-earning households and thereby heightening the divide as they then go on to self-segregate in affluent communities rather than return to their original, often rural, hometowns. Rather, the point is that when talking about wealth inequality, in particular, the conversation cannot be had in any meaningful way without factoring in the breathtaking decline in interest rates over the past 38 years.

Important note: Nothing in this post was intended to be, nor should be considered, investment advice. Any individual security or securities mentioned were selected solely as an academic example meant to highlight whatever concept was being discussed in the context of the post. Future conditions may change and make a particular example no longer accurate in the future due to fundamental changes in either the nature of a given enterprise, the economy, or the political environment.