After our discussion of The Walt Disney IPO earlier today, which was born out of Walt and his family consolidating three of the companies they owned underneath a single umbrella and issuing shares to the public to help finance the ever-expanding empire, including the creation of the Disneyland theme park in Anaheim, California, I thought it would be interesting to take a look inside the private family holding company he setup around the same time.

[mainbodyad]He ran this private family holding company parallel to Walt Disney Productions and used it in some interesting ways. It differed from the one Sam Walton used, Walton Enterprises, to hold his shares of Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., after the discount retailer’s IPO, but given the nature of Disney’s business, it makes sense what he did. Personally, I vastly prefer Walton’s method. It is more transparent, seems fairer to outside stockholders of the public business, binds the family together in a single economic entity working as a unit for the good of all the members, and consolidates power, but it’s always useful to study alternative arrangemenets.

The holding company was originally called Walt Disney Inc. It was created in 1953 when Walt and some of his design engineering employees formed a new corporation. After the IPO of Walt Disney Productions (later named The Walt Disney Company in the 1980’s to honor its founder; this is the business that you can buy shares of on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker symbol DIS), the firm changed its name to WED Enterprises so it wouldn’t be confused with the main, publicly traded business. Walt’s brother and co-founder, Roy, strongly opposed Walt’s creation of the company and thought that it was a crooked, selfish move designed to drain the coffers of the main business.

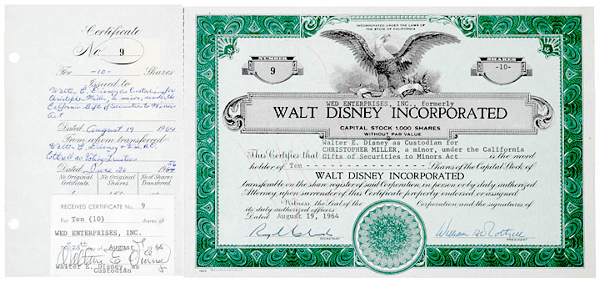

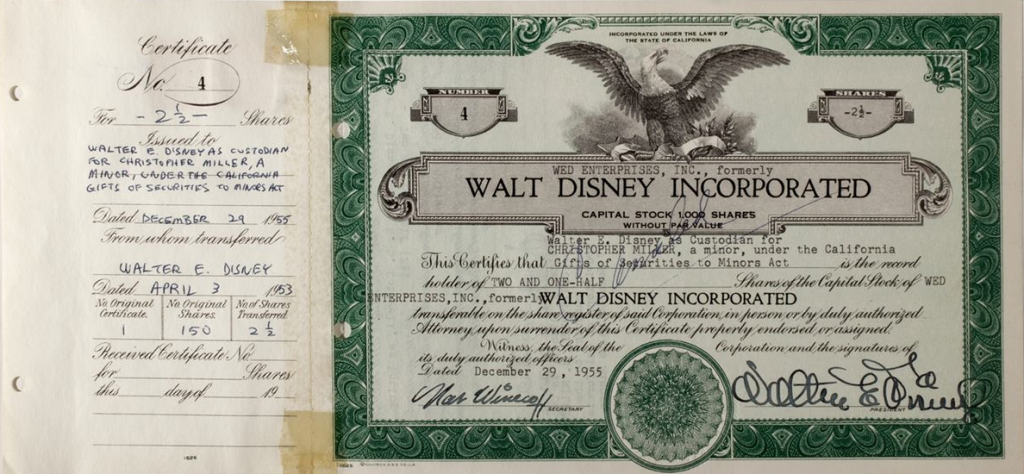

Basically, Walt Disney setup WED Enterprises and gifted shares of it to his heirs. For example, here are stock certificates that he gave to one of his young grandsons for 10 shares, and 2 1/2 shares, in the private company:

Walt then transferred to WED Enterprises a collection of asset and rights, including, but not limited to:

- The rights to his name and likeness

- Ownership of certain Disneyland rides, attractions, and assets such as The Disneyland Railroad, the Disneyland Monorail, the streetcars on Main Street, and the Viewliner. They cast members who ran these attractions were actually employed by an entirely different company than the rest of the park as they were on WED’s payroll.

- The licensing rights to merchandise sold by the public Walt Disney Productions, that entitled him to 5% to 10% of all revenue on items sold, such as stuffed animals, toys, games, etc.

- The rights to the television show Zorro

- The right to invest up to 15% of the cost of movies produced by Walt Disney so that his family could keep the money without sharing it with the Walt Disney Production stockholders. The bulk of the investments ended up consisting of a 10% ownership stake in 26 individual Disney live-action movies, the most successful of which was Mary Poppins. It is rumored the Disney heirs continue to generate millions of dollars a year from the income produced by these old films.

Some of the shareholders in Walt Disney Productions, which was traded over-the-counter at this point and not on a major stock exchange since the IPO hadn’t happened yet, sued Walt Disney because they believed he was effectively stealing money from Walt Disney Productions and its stockholders by using WED to divert cash to his own pockets, charging WED for work he should have been doing for the firm, and creating a significant conflict of interest.

And let’s be honest – it wouldn’t pass muster for most people. It looks shady. It was shady. Here was Walt Disney. You invested with him in an illiquid stock that had not yet had an IPO. Then you find out that he has setup another business, is charging your business that you thought you were in together all kinds of fees and licensing rights, and extracting the money for himself, his wife, his children, his grandchildren, and a few other people. Could he do it? Yes. Was the result good? No. His fellow owners felt like he was taking advantage of them. It’s human nature. On this one, Roy Disney was right. Walt should have listened to his brother. He should have been focused on Walt Disney Productions and gone all-in like Warren Buffett did with Berkshire Hathaway or Bill Gates did with Microsoft.

WED Enterprises Changes Its Name and Begins Diversifying

By 1965, the conflict of interest had grown so bad, and Walt Disney Productions, now a public company with many public stockholders, so dependent upon WED Enterprises, that it demanded WED sell it certain assets, as well as change its name. In 1965, the transaction closed, and WED no longer owned those assets, which were now the property of the public Walt Disney Productions. Armed with cash, WED changed its name as required in the buyout contract. It settled on Retlaw Enterprises, and began diversifying.

According to the L.A. Times, the first asset the Disney family bought through the now-renamed Retlaw Enterprises was a television station in Fresno, which started an acquisition spree that ultimately resulted in the Disney family’s private holding company owning a jet charter airline, more than half a dozen CBS affiliates, and nearly 1,200 acres of farmland and undeveloped real estate in Southern California.

In 1982, the public Walt Disney Productions wanted to be done with Retlaw entirely, and offered to buy everything related to the Disney theme parks so they could go their separate ways. At this point, Walt had been deceased for 16 years. It was tiresome and insulting that the namesake, enormous, publicly traded Disney empire didn’t even own its own iconic monorail.

If you dig into the old Securities and Exchange Commission filings around the time, you find out how shocking the figures were. Between 1955 when Walt Disney Productions began to get ready to go public and the end of fiscal 1981, Retlaw had charged Walt Disney Productions $75 million for use of the monorail and Disneyland railroad. It was absolutely ridiculous. Roy Disney was right – the public company, Walt Disney Productions, should have owned those assets from the outset. It really was just a way for Walt to pocket more cash and, just as importantly after the Oswald incident, let him exercise God-like control over the company. He always had nuclear switches that he could push if people challenged him. Can you blame him? I understand the impulse to put in insurance mechanisms that insulate you, especially when you are taking creative risks.

Walt Disney Productions gave Retlaw 818,461 shares of stock to be done with the entire arrangement, which the Disney family members who owned Retlaw took for themselves instead of reinvesting it back in the business; that way, they could each hold shares of the public Disney business individually instead of as a group. Roy Disney once again objected strongly, saying the transaction was overvalued and it was simply a way for Walt’s heirs to take even more cash and ownership out of the public business. He was overruled. Again. I think Walt Disney Productions just wanted to be done with the heirs. At least, that is what the evidence looks like.

[mainbodyad](Note: I don’t think the heirs necessarily did anything wrong. I actually love this idea that they are still living off the amazing things their father and grandfather created, even though I, personally, wouldn’t be emotionally fulfilled if all I had in life were the results of someone else’s efforts. My comments are referring to the abstract ethical ramifications of conflict-of-interest situations like this. If your grandfather were Walt Disney and he gave you shares of a private holding company through which he owned partial rights to Mary Poppins and the transportation at Disneyland, aren’t you going to be happy about it? Wouldn’t you love the stock? I would. I think it would have been better and looked fairer if Walt had, instead, just structured the main public business in a way that achieved the same ends; he could have done what The Washington Post did and given himself a special series of Class A or Class B shares that had the right to elect a majority of the board of directors. He could have paid himself in stock options. That way, everything would at least be crystal clear.)

With the naming rights and other assets now firmly in its control, Walt Disney Productions, a publicly traded behemoth, changed its name to The Walt Disney Company.

By the late 1990’s, Retlaw sold off its remaining television and media assets, which the L.A. Times says in the related story were worth $215 million in cash.

In 2005, 39 years after Walt Disney’s death, Retlaw had been wound down to a fraction of its former self, with Walt’s heirs having taken hundreds upon hundreds of millions in capital distributions and dividends out of the firm for their own personal lives and investment portfolios. At this point, they transferred Retlaw Enterprises to a non-profit called Walt Disney Family Foundation, which runs a museum in San Francisco filled with details, items, and collectibles from Disney’s life. It is run by Walt’s daughter, who is now 80 years old.

What is funny is that Walt’s heirs repeated the same behavior when setting up the foundations. The Walt and Lilly Disney Foundation is where Walt’s wife put most her fortune. Beginning in 2006, the foundation started giving away a lot of the $252,686,699 in assets it had sitting on the balance sheet so that it had $157,169,439 by the end of fiscal 2011. Yet, almost all of the money is going to other family-run Disney foundations. For example, more than $10,000,000 was given to the Walt Disney Family Foundation (the now-parent of Retlaw Enterprises). By structuring the WDFF as a private foundation and not a public charity, the Disney family can get around the disclosure laws so people can’t know what they are taking in salaries and benefits. Apparently Walt taught them well. I have absolutely no evidence for this, and am not indicating that I think the Disney family is doing it, but one technique for wealth preservation is to hire the heirs to run the foundations like this so that you can pay them very large, six or seven figure salaries, while lowering your overall tax bill. If they are doing it, it’s perfectly legal so I see no problem.

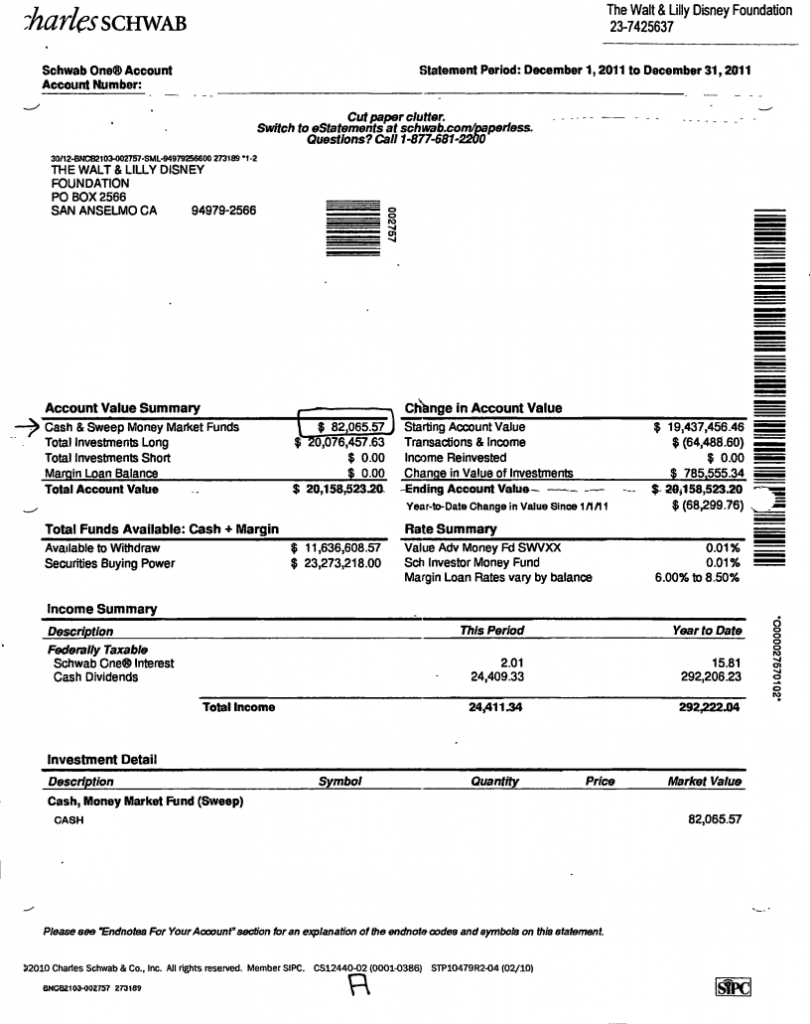

The investment choices, and where the money is parked, is also interesting. I find it odd that one of the non-profits, The Walt and Lilly Disney Foundation, has 462,354 shares of Walt Disney common stock just sitting in a Charles Schwab account with margin privileges. The stock has almost doubled since then so the shares would be worth a lot more than the statement shows here:

The Disney foundations have money parked everywhere, in the oddest places and with a strange mix of assets … You can click to download a set of financial statements for one of these foundations (PDF format).

You should see Walt Disney’s will. It is deserving of its own post. He used a series of trust funds and shares of Retlaw Enterprises to effectively make sure his grandchildren inherited a vast fortune, and that it was tied up in a way nobody could screw it up. This man was a shrewd, ruthless business titan. It’s hard not to respect how he marshaled the limited resources he had to create something bankers and investors thought insane. This was not some pie-in-the-sky animator. He knew exactly what he was doing. He used capital structures and legal entities like tools, fitting them together to give him the money he needed to accomplish what it was he wanted at the moment. There are actually a lot of parallels in the ways he set this up between Disney and Maurice Greenburg of AIG, who used a private company called C.V. Starr & Co., Inc. alongside his public enterprise. The founding family of American Eagle Outfitters also has a deal like this, though they’ve hidden it fairly well. They own a real estate company and then have the public business lease from the private real estate holdings, generating de facto dividends for them.

I didn’t expect to spend my night digging through obscure legal databases and foundation tax filings but this has been fun. It definitely gives me an appreciation for the working parts that made up the Disney empire. A fully formed media conglomerate like this doesn’t just spring up over night. It is the result of decades of individual decisions, changing arrangements, and ownership profiles.