I mentioned yesterday in the post about Japanese Gyoza that we had seen Maleficent twice this week in theaters. With time to reflect on the film, I keep coming back to the economic power of certain types of enterprises. It reminds me of a story from a speech Warren Buffett gave two decades ago to a group of college students in North Carolina detailing his worst investment mistake up until that point; a story he first began telling in 1991 when the damage had crossed $1 billion. I heard it when I was in high school and it’s always there, in the back of my mind. I went through books, transcripts, articles, and video clips in those days to try and find more information, assembling a pile of research that, I hoped, would help me in my own career.

In 1966, the entire Disney company was selling for $80 million and had a debt-free balance sheet. Warren Buffett spotted this. He went out to Southern California and met with the Kansas City boy who ran the place, Walt Disney. Disney showed him around the property and talked about the newest attraction they were installing, the Pirates of the Caribbean, which cost $17 million. A stockholder was essentially getting much of the empire (sans that held in WED Enterprises), copyrights and all, for the price of a handful of rides. The reason Wall Street had no interest in the company was that it was earning a lot of money from Mary Poppins but there was nothing in development pipelines so income was bound to fall.

Convinced there was something there, and satisfied with the economics, Warren pulled the trigger. He used $4 million of his partnership capital to buy a 5% ownership stake. His thinking was that the firm had 200+ films in the vault that could be brought out over and over for future profits, they had 300 acres in Orange county where the Anaheim park attracted 9 million customers a year, there was a brilliant executive at the helm who had a lot of his own money invested in the place; a good recipe when combined with a dirt cheap price and a huge margin of safety.

A year later, Buffett sold the stake for $6 million. At the time, he felt good about it. In his mid-to-late 30’s, he’d made his partners the inflation-adjusted equivalent of $14.1 million in roughly twelve months with a single decision. However, in retrospect, it was one of the worst mistakes of his long and illustrious career. Warren’s original thesis turned out to be correct. The Disney company did have a special sort of business model that allowed it to continually profit from old intellectual property over and over, again, just like The Coca-Cola Company has return on capital advantages that make it mint money. As I’ve mentioned in the past, Buffett’s business partner, Charlie Munger, refers to Disney as an oil company that pumps money out of the ground, then puts it back for a generation to return to it when the time is right. The trick is to make sure you aren’t overpaying for the stock. Write the check when the price is too high and it’s like buying a steamship stuck in a swamp. It can take a lot of years for the underlying profits to catch up to the acquisition cost while you sit there mired in the muck.

The 36-year old Buffett controlled 5% of Disney’s company using his partners’ money. They paid $4 million. Around a year later, he sold it all for $6 million, pocketing a $2 million profit for his investors. Today, it would be worth $7 to $12 billion.

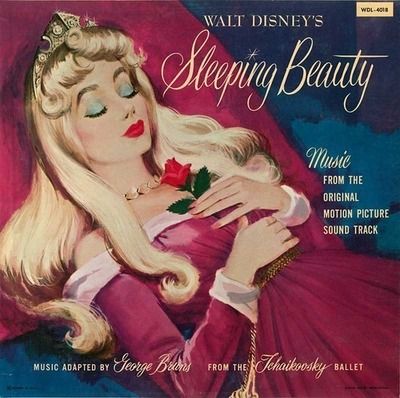

Right now, in theaters, Sleeping Beauty is being retold, the same theme song resold … It’s a given that the Maleficent movie is going to make sales of the older, original movie increase, as well as toys, merchandise, backpacks, apparel, costumes, candy, and every other imaginable sundry. It’s a self-reinforcing cycle that strengthens past cash generators with each new expenditure, getting a sort of double-bonus. This drives families to the park, which reinforces their brand affinity, further strengthening the feedback loop. Power builds upon power.

More than half a century has passed – 55 years to be precise – and Disney is still minting money off the expenditures it laid out when it created Sleeping Beauty in 1959.

Next year, the script will be repeated with Cinderella. The brand equity is so incredible it doesn’t even need a movie title on the posters! That is the result of generations of capital expenditures and marketing reinvested into the company so you have grandparents, parents, and grandchildren enjoying franchises together. In my own family, my niece and nephew could easily go see this with their great grandmother. Talk about timelessness and relevance.

In the case of Cinderella, the new installment released in 2015 will come 65 years after the original was made, with stockholders still cashing dividend checks from the brand equity created in 1950.

The new Cinderella posters don’t even have to have the name of the movie on it. Everyone just knows. That’s power.

How bad was Buffett’s mistake? Updating the calculation with a few, quick, back-of-the-envelope adjustments, it looks like the position would be worth somewhere between $7 to $12 billion today, including dividends and spin-offs. Had he opted to plow any and all distributions back into the firm, the wealth would be exponentially higher. The Disney stake would be far more diversified as it now has exponentially more movies, several times the number of theme parks, one of the largest hotel businesses on Earth, the largest sports network in the world, its own branded television channel, and many more studios pumping out content including Pixar, Lucasfilm, and Marvel.

When you understand the implications of this, it can change the way you think about portfolio management. The greatest investor of the 20th century could have thrown in the towel at 36 years old, sat on his behind, and done nothing but hold a block of shares in a company he knew was inherently superior to the typical enterprise. With zero activity for almost the past 50 years, he still would have ended up a billionaire, and created a lot of wealth for his partners along the way. As he points out, this mistake never shows up anywhere. It will never be on the income statement or balance sheet, explicitly identified. Yet, it’s real. To paraphrase his sentiment, mistakes of omission are just as dangerous as mistakes of commission. People fail to recognize this because of a cognitive bias arising from human evolution known as loss aversion.

How Much Is Too Much To Pay for a Good Business?

This poses the question, “How much is too much to pay?”, which some of you have sent me in the contact form and in the comments section. I’ve avoided answering because I’m trying to come up with a mathematical model that can at least approximate how you should think about the problem. It’s really a sliding scale of probabilities with the potential for higher rates achieved the lower the valuation relative to earnings growth. Putting it in a simple, easy-to-digest format, or at least coming up with a narrative that will let those of you without a lot of experiencing internalize the relationships, is one of the things I’d like to get done in the next month.

Disney is, in my opinion, slightly overvalued at the moment. That means you have a situation where there are only three possible outcomes:

- The earnings growth exceeds the rate used in my valuation models, supporting the current price and, depending on how far the excess, potentially driving it to higher levels

- The stock price declines until the underlying profits can support the current number, returning the share price over time to its existing levels

- The stock price treads water until the underlying profits can support the current number

The complicating factor is, for a business like Disney, you might notice overpaying 5 years from now, but you’re not going to care 25 years from now, at least not at the modest level of overvaluation that currently exists. (We aren’t in insane territory like the 1990’s. This is not Wal-Mart at 50x earnings or anything.) Looking forward to the end of the fiscal year in September, we’re still only talking about a 5.5% expected earnings yield with a decent growth rate. Park ticket prices were just raised by double digits, which I plan on using as an economic illustration in a future post.

This is the art side of investing. Nobody knows if Disney shares will be $50 or $125 sixty months from now. What is reasonably certain is that an owner of Disney has a higher than average probability of doing very well over the coming quarter century. This is especially true if you can build up a big deferred tax advantage and then leave the shares to your kids or grandkids, bypassing the capital gains tax rate entirely so none of it ever goes to the government. As long as you’re doing this with a few dozen assets in your life, be it apartment buildings, a private company, or a portfolio of blue chip stocks, you don’t have to watch one particular pot too closely. While you wait for Disney to come to fruition, your attention can be on developing that new set of townhouses you plan on leasing out to tenants or adding to your General Mills stake. Experience has taught me that when dark skies appear – and they always come – the people best able to ride out the storm without a lot of distress are those who have wealth coming in from non-correlated asset classes and projects. It’s a lot easier to watch 70% of your stock portfolio seemingly disappear, and wait out the years it may take for the price to return, when you own the local strip mall and are collecting rents from your tenants.

You Throw It On the “Too Hard” Pile and Dollar Cost Average, Letting the Highs and Lows Balance Out Over the Decades

For a lot of people who enjoy the game but don’t want to work too hard, the most intelligent course of action when stumbling across a company you want to own for a long time is to sign up for the direct stock purchase plan so you buy a set amount through dollar cost averaging every month under the premise that the highs and lows will average out over the years. As long as you don’t stop contributing during stock market crashes, that has proven to be true. A couple of buys at the bottom can undo a lot of damage from purchases made during the peak when things return to a more mitigated normal. In fact, if we were to wake up and Disney be at $40 tomorrow, it should induce cartwheels.

The Lessons We Can Learn from Warren’s Loss

When I study stories like this, it reminds me:

- No matter how smart you are, you’re going to make mistakes. Accept it. Have a sense of humor about it.

- If you keep your batting average good, and avoid wipeout risk, it still works out in the end in most cases provided you live long enough.

- Sometimes, a quick profit can be a big long-term loss. There are only a handful of businesses in the world that are truly exceptional due to competitive advantages that are hard to replicate and difficult to destroy. If you get your hands on one at a decent price, hold on for dear life, through bubbles and bursts, booms and busts, and everything in between.

- Everyone is aware of at least a couple of these exceptional businesses and often will do nothing about it for as long as they live. They’ll spend their whole life knowing what they need to know to build a fortune and never lift a finger to make it happen. There’s a disconnect between the knowing and the doing.

On a non-related final note, once I’ve finished the other 2-3 posts I intend to write using Disney as an example, I’m going to try to lay off it for the case studies, just as I did with Coke last year, McDonald’s before that, and General Electric a few years prior. It gets boring using the same enterprise over and over since I’m so familiar with it already. The problem: I like to try and stick to Dow Jones Industrial Average components when using real world figures so they are companies everyone reading this blog owns (even if through an S&P 500 index fund). That doesn’t leave me many options since some businesses have inherent accounting complexities (e.g., Merck, Pfizer), bizarre capital structures (e.g., Visa), are highly cyclical (e.g., DuPont), or subject to rapid technological change that makes predicting future earnings more than a few years in the future a fool’s errand (e.g., Intel or Cisco). I suppose I haven’t talked about 3M, yet. It’s 112 years old and still selling Post-it and Scotch tape. I’m just not sure how digitization of work processes is going to influence its bottom line over the coming decades, partially because I’m not even sure if office supply businesses will be able to survive at some point. That day may be far off but I think it’s coming.