Thoughts on the United States Returning to a Normalized Interest Rate Environment, the Housing Market, and Related Topics

Do you like charts and graphs? Brace yourself. I’m going to give you charts and graphs.

Anyone who has read anything I’ve written post-Great Recession knows that I have long criticized the Federal Reserve’s deranged policy of keeping interest rates too low for too long. So many of the societal ills we now face are not the result of tax rates, or inequality, or any of the other usual scapegoats you hear. Rather, at their heart, they come down to policymakers breaking capitalism in the short-term to prioritize the savings of the top 20% of households by avoiding temporary pain. Money essentially became free, and the opportunity cost of funds was warped and manipulated in a manner that profoundly twisted the ordinary functioning of everything from the housing market to the way retail investors thought about market risk in managing a portfolio of common stocks. (One of the only things positive I can say about the experiment is that, unlike Europe, the U.S. never went so far as to force negative rates, which I likened to quicksand. Good luck getting out of it absent Keynesian war-time spending.)

Once the Fed did start raising rates, they had waited so long to do so that they were forced to aggressively hike at a pace never before seen in American history, causing significant collateral damage. As I have shared in other venues, last year, for example, was the single worst year for bond market returns in American history, not to mention the 7th worst equity market year. Plus, there were numerous financial institution failures due to 21st century honest-to-God bank runs that, themselves, were caused by institutions relying upon guidance from the government. Specifically, anyone who trusted the Fed to do what it said was nearly wiped out. The situation is so absurd that – and I am being 100% serious right now – government banking regulators were convinced we would never face another rising rate environment, at least over a brief period of time, so they stopped stress-testing for rapid changes in the interest rates and what it means for quoted market value of bank assets prior to maturity. You know, one of the foundational risks, known as a duration mismatch, anytime you are lending money.

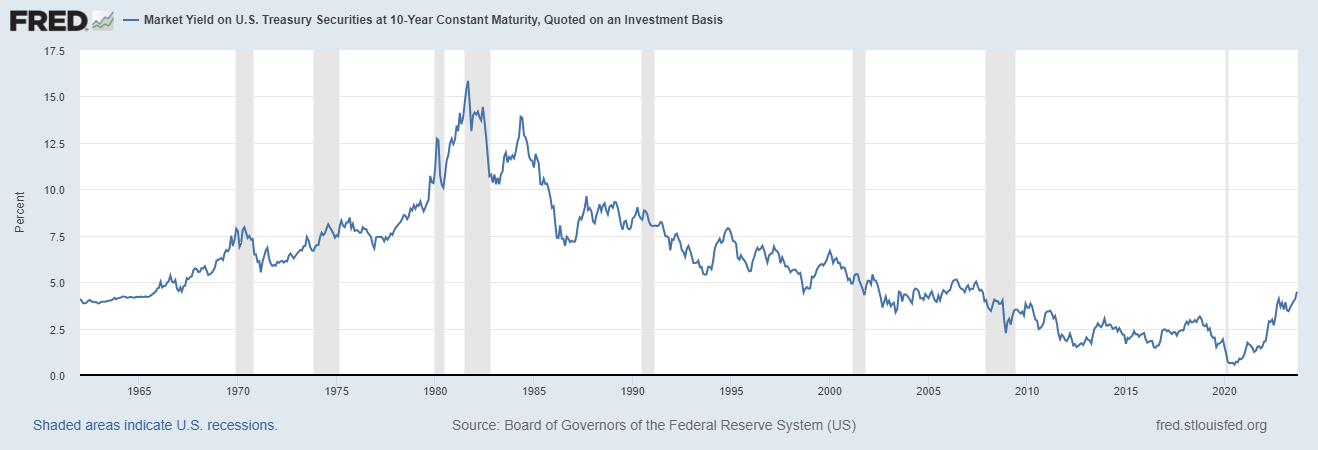

Still, despite the progress the Fed has made, I don’t think they’ve gotten the job done long-term. One-year Treasury bills yield 5.46% while the 10-year is 4.44%. It’s impossible to say but, if you really pressed me, I think the latter needs to be somewhere between 6.50% and 8.00% or so, for at least four or five years, to start undoing some of the damage it caused. That seems like a sufficient amount of time to psychologically re-train society to think properly about the time value of money and risk-adjusted returns. That should put us back in the range of usual American post-war experience and reverse the absurdity of the past decade.

I would argue that a lot of folks still haven’t come to terms with what this means. They have become so used to a low-rate environment that is both a historical anomaly and not sustainable that they are in for a major wakeup call.

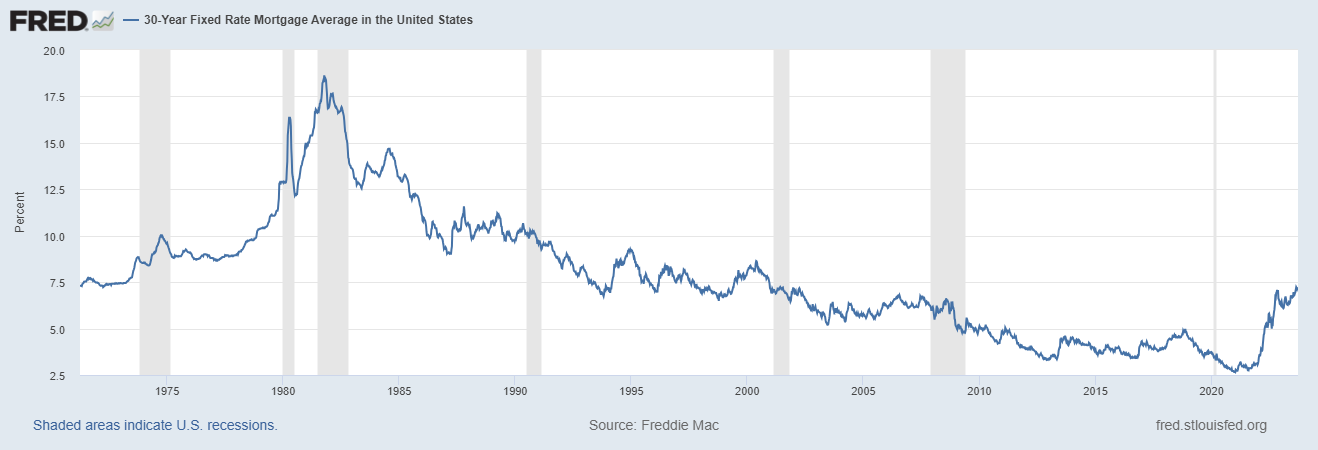

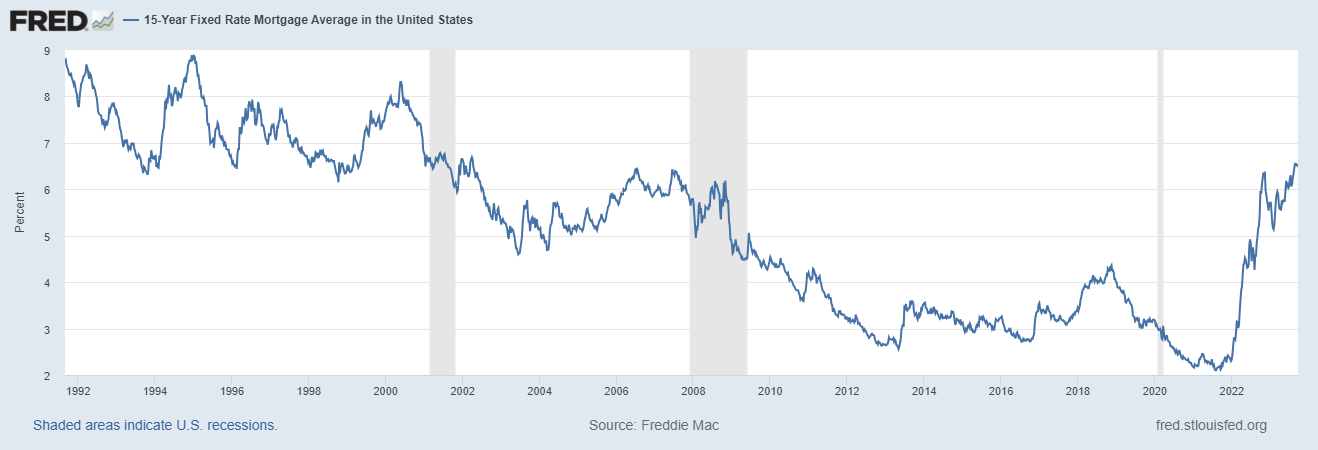

Consider housing. There is a lot of talk about these “high” mortgage rates being temporary. Yet, folks don’t seem to remember that in the past, if you got a rate of 5%, that was incredibly cheap; something that hadn’t happened in a long time. Combined with tax deductibility and an ordinary inflation rate of 3% to 3.5% or so, many families effectively achieved a near-neutral, or even negative, real rate on the debt. Even without appreciation, the opportunity cost relative to renting was attractive. Down payments were modest relative to median income. Home prices overall were modest relative to median wages.

Take a look at the historical average 30-year fixed-rate mortgage in the United States using the maximum data points the Fed makes easily available.

Now the same thing, using the maximum data points the Fed make easily available, for the average 15-year fixed-rate mortgage.

Unless we face a national disaster on scale with the Great Recession, September 11th, or 1929-1933, the odds of rates ever going back to what folks have grown used to over the past decade are remote. Even if they do return to that territory, policymakers seem to have learned their lesson and aren’t likely to keep them artificially depressed for any longer than reasonably necessary.

The challenge? Stay with me here. We’re going to have to get into some numbers.

Interest Rates Will Be a Major Driver of Residential Real Estate for a Long Time

A Look at Owner-Occupied Housing Statistics Including Mortgage Data for the United States

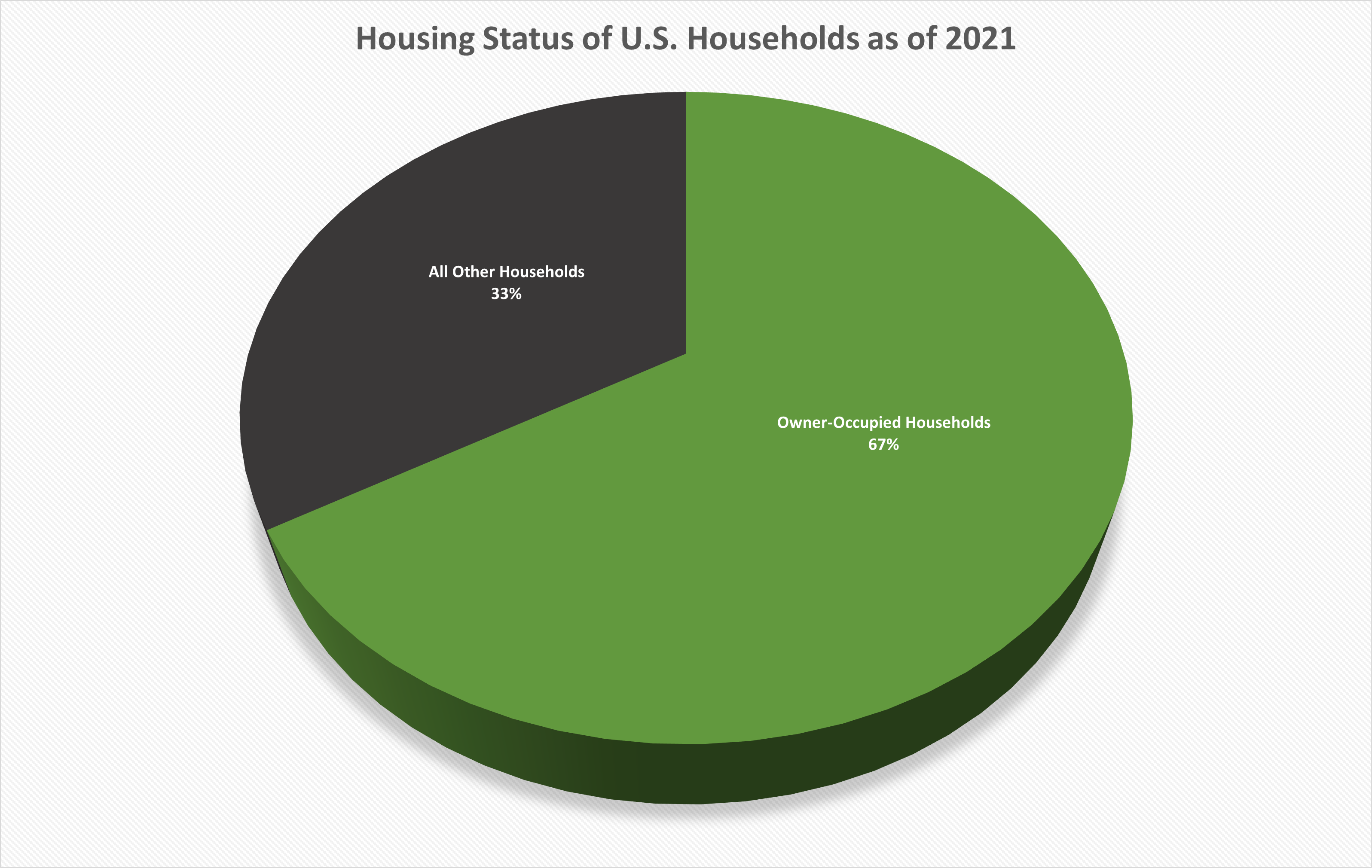

First, let’s start with the fact that as of our most recent data set, the United States estimated that there were 124,010,992 households in the country as of 2021 [Source].

Let’s go back and look at the most recent data set from the American Housing Survey (AHS) from the U.S. Department of Commerce via the Census. (If you enjoy looking through data sets yourself, I’ll make the spreadsheet available for download here: [Source XLSX]) That way, you can run your own analysis and see even more details than the ones we are going to discuss. In addition, beyond the scope of what I write about in this post, you might also want to check out the National Mortgage Database (NMDB) Aggregate Statistics by the Federal Hosing Finance Agency. It’s a great source of data, too.

In 2021, there were 82,513,000 owner-occupied housing units in the United States. This meant that for every 100 households in the United States, approximately 66.5 of those households lived in a house that they owned themselves. A literal super-majority. To make this somewhat easier to follow if you are busy, I’ll create a couple of pie charts rounded to the nearest whole percentage point as a visual aid.

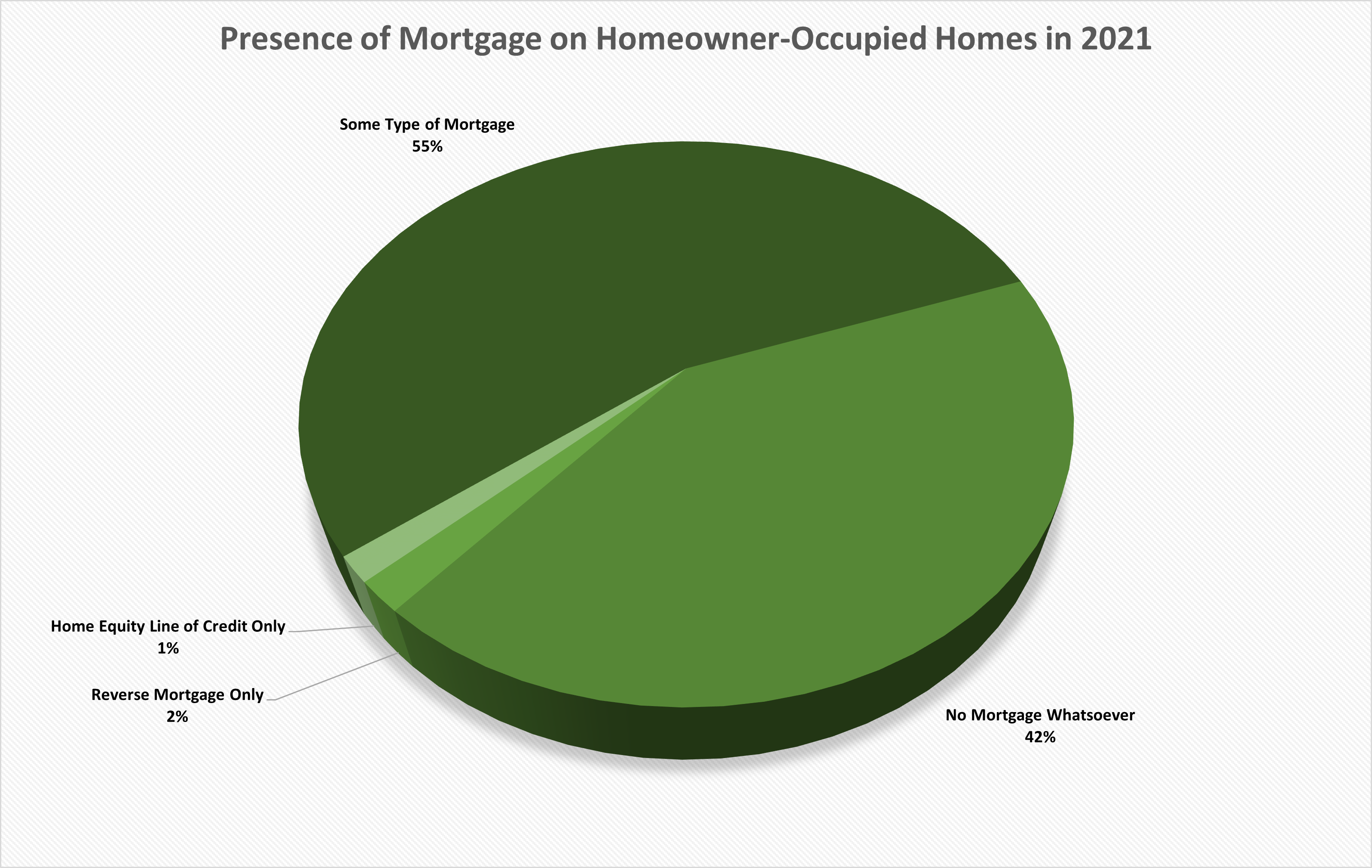

So we know a super-majority of American households live in an owner-occupied home. What is the financial situation of those owner-occupied homeowners? If we dig into the mortgage statistics on the properties, we find that of those 82,513,000 owner-occupied housing units in the United States:

- 34,540,000 had no mortgage whatsoever

- 1,474,000 had a reverse-mortgage only, meaning it was an appreciated and/or paid-off property that (most likely an elderly) person or couple used to finance the final years or decades of their living costs while retaining their residence.

- 1,232,000 households had paid off their house entirely except they established a home equity line of credit to access liquidity at a low rate with potential tax deductibility

That is …

Before we move on, I want you to consider what this means. It means that 27.85 out of every 100 American households live in an owner-occupied home that has no mortgage against it whatsoever. It’s free and clear. (In some states, like California, that number is higher if you look at other data sets.)

If we add in the other categories I just mentioned, it gets us up to 30 out of 100 American households that either own their house outright or have either a home equity line of credit only against a paid-off house or a reverse mortgage to extract equity from a previously paid-in-full home.

Follow me so far? Okay, good.

This means only 45,267,000 out of the 82,513,000 owner-occupied housing units had what we might think of as a true mortgage. That is only 54.86 out of every 100 owner-occupied houses. That is 36.5 out of every 100 American households.

What does their situation look like?

- 43,672,000 of those remaining 45,267,000 mortgages were fixed-rate, self-amortizing loans

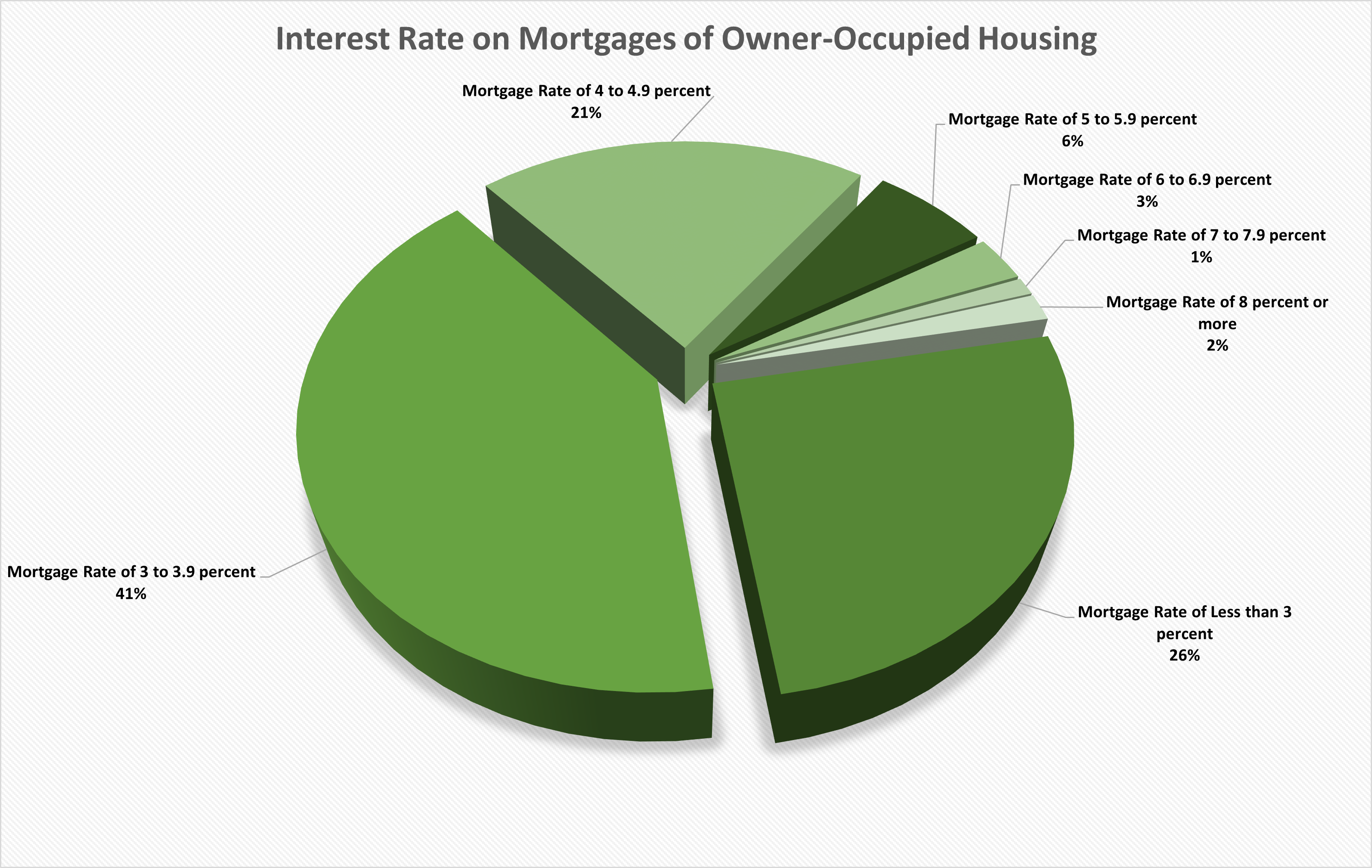

If we look at all mortgages across the board, we discover that:

- The median interest rate is 3.5%

- The average average (mean) interest rate is 3.7%.

If you dig a little deeper and examine the make-up of those numbers, you discover an astonishing 11,653,000 of households are paying a rate of less than 3%. Net of inflation and tax deductions, the real cost of borrowing is significantly negative. From a purely financial (rather than emotional) perspective, it is foolish to pay off debt with a negative cost. The money should be parked in U.S. Treasurys yielding roughly 5.5% and blue chip stocks with a special emphasis on companies that boast strong balance sheets and dividend yields in excess of 3% per annum, preferably those that have a long history of hiking the dividend rate (while keeping the payout ratio relatively stable) at a pace in excess of inflation indicating pricing power in the underlying enterprise. Doing nothing differently, a household with the same income, and same expenses, who followed that path has a greatly improved probability of materially higher wealth at the end of twenty or thirty years. This is especially true during periods when stocks are declining and becoming cheaper relative to long-term earnings. Note that if you don’t need the money, and are willing to deal with the potentially large sacrifice in future wealth, paying off a mortgage under these conditions can still make sense if it brings more emotional joy than the money would provide you because, at the end of the day and as I have always said, money is a tool. That’s it. It exists to serve you to build the life you want.

Visually, here is what it looks like. To make it easier to read, I’ll expand the pie chart a bit.

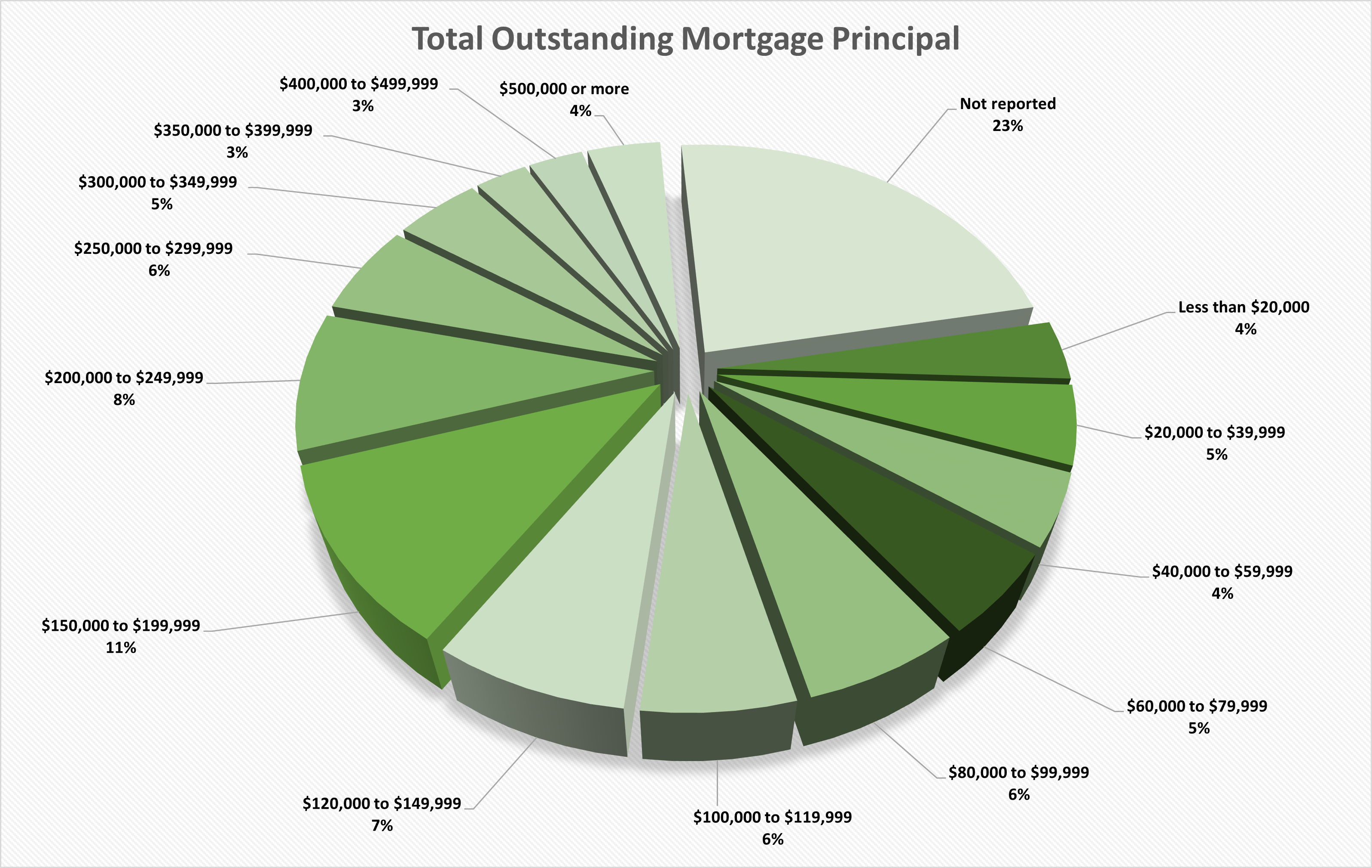

That’s not all. Not only do a staggering number of people own their houses outright, and those that do not have the best interest rates in history locked in at long-term fixed-rate terms, but the actual debt itself is very, very small relative to the typical America’s household income and/or net worth. Leaving aside the portion of mortgages for which data is not available, the median mortgage balance for those with a mortgage is only $150,000.

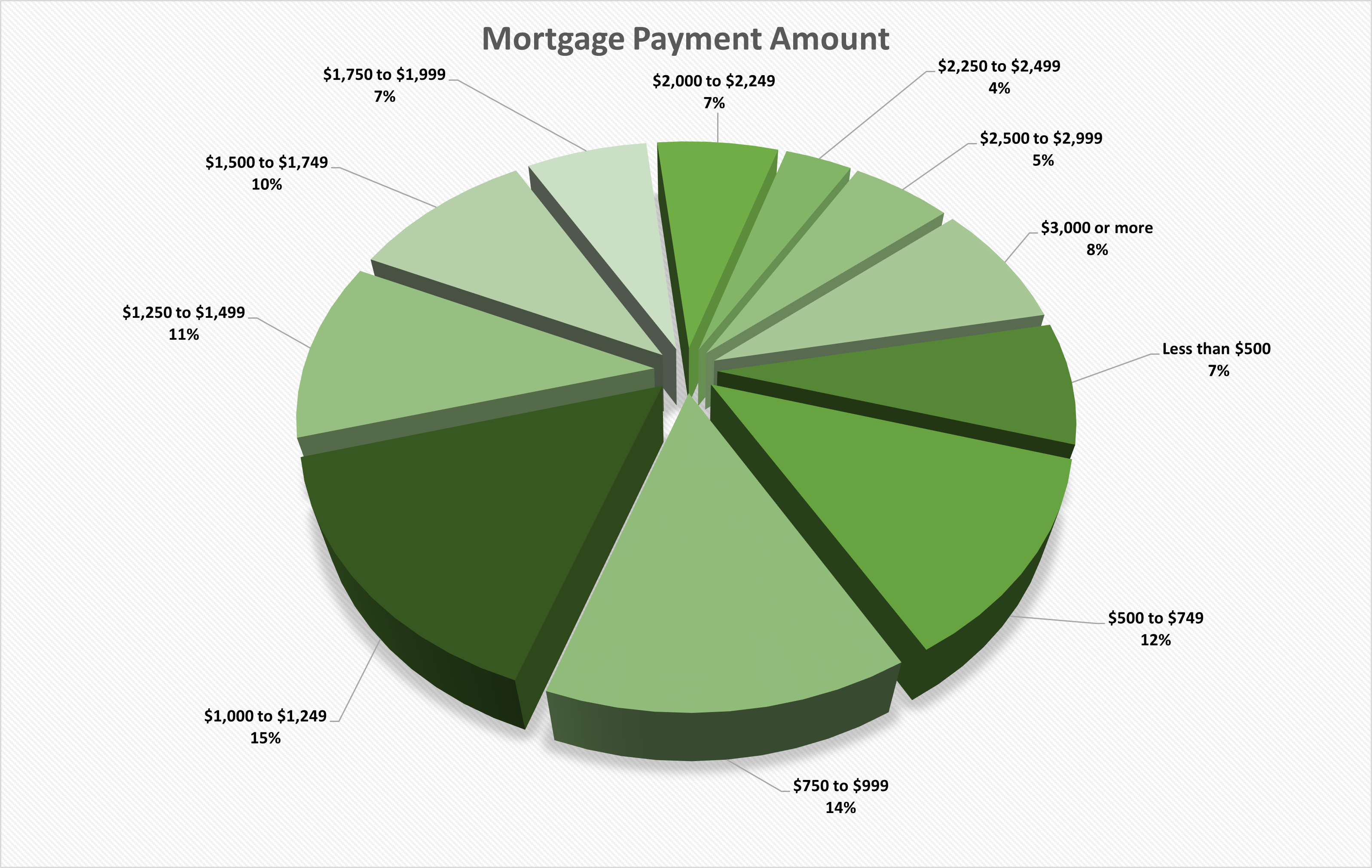

We’re not done, yet. The median monthly payment for those who have a payment at all is only $1,275. Even more astonishing, 15,124,000 of the owner-occupied households that have mortgages have a payment of less than $999.

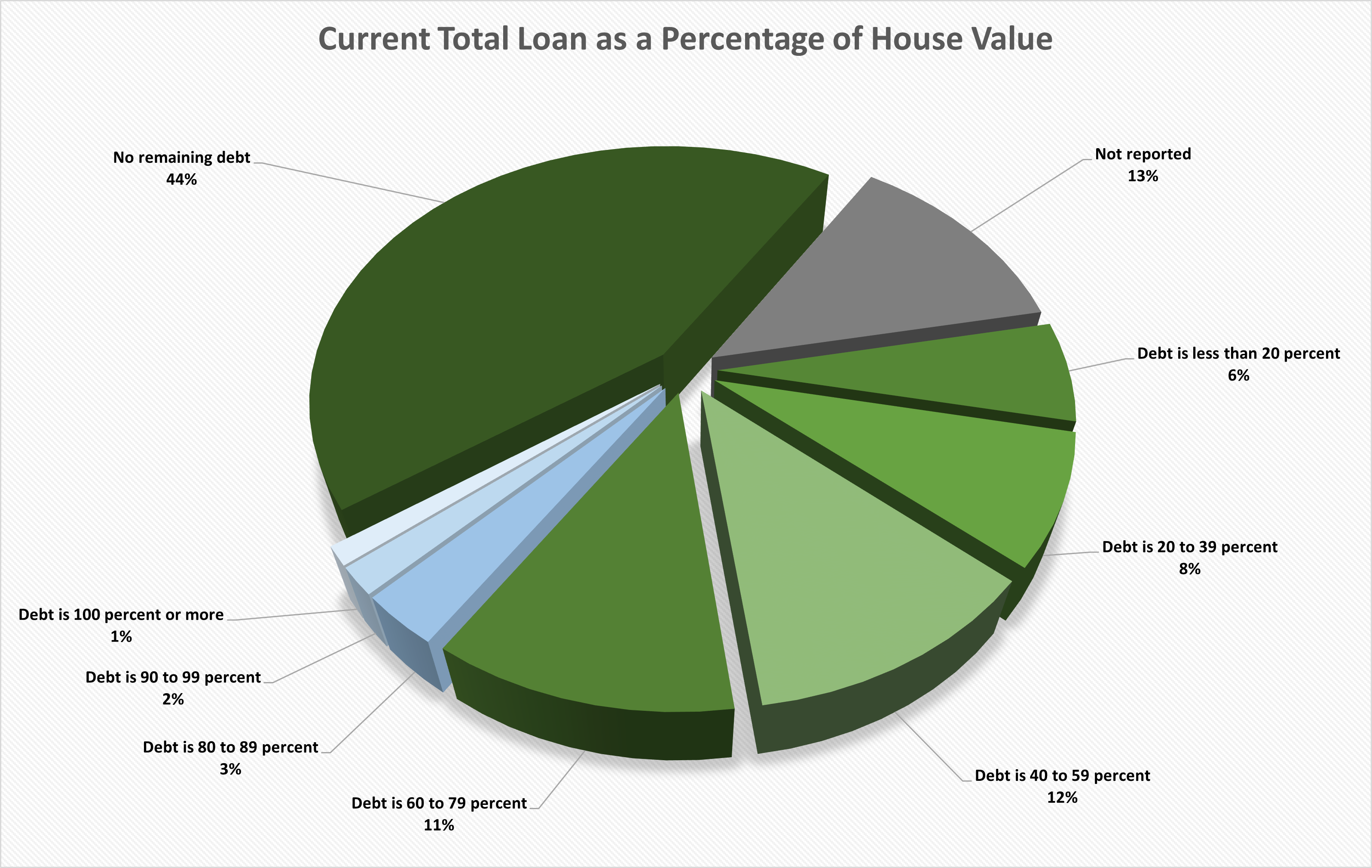

There’s one more, thing, too. These houses have enormous equity backing them. When we look at the debt as a percentage of the property value as of 2021, we find the following. I’ve shaded houses that are paid in full, or which have at least 20% equity, in green and houses with less than 20% equity in blue. (Note in the chart below that the “No remaining debt” is slightly higher than the paid in full values from earlier because some homeowners are in the final month, or months, of wiping out their mortgages and others use a home equity line of credit they wipe out from time to time so for all intents and purposes, the “real” paid-off figure is higher than the original numbers showing no mortgage.)

To recap, we’ve learned:

- A super-majority of Americans live in owner-occupied houses.

- A massive portion of those owner-occupied houses are owned outright with no mortgage debt at all against them.

- Those who do have a mortgage debt are almost all locked into long-term, fixed-rate mortgages.

- The interest rates on those mortgages are the cheapest in history and below the rate of long-term inflation. With tax deductibility, it represents a negative cost of debt for many homeowners.

- The absolute amount of the mortgage debt is low.

- The payments are absurdly low.

- The equity cushion built into the housing market is enormous.

What are the implications of this data?

- Housing prices could collapse and most people would still be above water.

- Even if they weren’t above water, they could still easily afford the payment so it wouldn’t matter as the opportunity cost of moving (either buying a new house with a higher mortgage double or triple what they are paying, or renting) is much higher.

- The biggest threat to people being able to afford their home is either widespread joblessness from a severe recession or rising property tax assessments that swamp the ability of homeowners to pay, especially fixed-income retirees.

- Many sellers are going to be existing homeowners who sell their appreciated home and, armed with liquidity, make all-cash offers, pushing out younger families that need or prefer to use a mortgage.

- A massive part of the U.S. population is effectively locked into the strongest “golden handcuffs” I’ve ever seen in any data set in American history. This will absolutely influence whether or not people can relocate for work, start businesses, and “right-size” their home for optimal allocation among the population (retirees trading down with young families getting larger and larger homes to have more kids). The reverberations of this might be ringing for an entire generation. Anyone under 40 years old who didn’t inherit money should be enraged. This was a policy choice. This damages American society and reduces the flexibility and dynamic nature of its economy. I don’t think it’s hyperbole to say that the Federal reserve has created something akin to a caste system or a landed aristocracy that divided the nation into winners and losers based on the generation into which they were born. In other words, this was generational warfare rather than class warfare.

The most efficient ways to fix, or at least alleviate, this are:

- Mass building, including smaller single family homes, rowhouses and townhouses, and large apartment complexes. Supply and demand ultimately exert an even greater force on real estate than even interest rates. If you doubled the number of housing units tomorrow, housing prices would implode. It’s that simple. No politicians or economist could stop it. There’s a lot you could do to encourage this, some of which would be distasteful to voters in the short-term. For example, you could set the tax rate to 0% for any developer project that involved constructing single family homes below a certain size (akin to what was built post-1950s) and meeting certain conditions that were sold to actual individuals and families who would receive subsidized mortgages in exchange for staying there for at least five years. This should go a long way, too, to reducing the pressure on apartment rents.

- Set the tax rate for large-scale Wall Street-run investment funds buying single family homes to double or triple the rate that applies to stocks, bonds, etc. to disincentive the financialization of the housing market. Better yet, ban it entirely as a matter of public policy. Note I’m not talking about wealthy people owning multiple investment properties. I’m talking about multi-billion dollar hedge funds going to folks, raising capital, using computer algorithms to mass purchase houses, and creating monopoly-like conditions in certain areas to create rent-seeking/wealth-extracting conditions.

- Homeowners with no mortgage cashing out, moving into smaller condos as they retire (presumably adding the surplus savings from the sale to their investment portfolio to increase their retirement income) and adding some inventory to the housing market for younger families.

- Real estate taxes getting so bad it forces people to lose their home. There will be political pressure to stop this but that sort of “do good” pressure is precisely what led us into this mess in the first place as the Federal Reserve manipulated the markets following the Great Recession.

What will not work, and what will make the situation far worse based on decades of irrefutable evidence are policies such as rent control or other artificial caps on costs. For example, California is largely facing the situation it is with non-affordable housing for most of its workers because of the constitutional amendment that essentially caps the rate of increase on property taxes so it does not truly reflect market price. That might have saved a bunch of senior citizens in the 1970s and the 1980s but the long-term cost to Americans, including those who would shortly be senior citizens a few years later, was far too great. There is no reasonable chance I see of California lowering its income taxes and significantly increasing its property taxes, which should be how things are funded if the goal were to eventually make the system work better for more people. There are too many vested interests and politicians will never collectively have the wherewithal to prioritize better long-term outcomes over short-term pain on a scale so large. Only in war do you see societies respond with that kind of discipline and conviction.

We also have to recognize the fact that this one issue – housing affordability, which is the end-result of the interest rate suppression of the Federal Reserve – is among the primary reasons so many voters, particularly younger voters, are miserable. There is a general sense it is impossible to get ahead; that they were born too late. Of course, things will get better someday, the question is will it get better in time for those generations or will they be “lost”, for lack of a better term.

Additionally, one risk to the housing market at the moment is the state of the commercial space. Commercial real estate looks to be a time bomb on the balance sheets of a lot of regional banks unless the Fed lowers rates next year. It’s possible the country escapes without that bomb detonating. However, it is worrying to the point I think anyone who needs commercial space is probably going to be able to get a far better deal a year or two from now than they can today. The numbers just don’t line up for a lot of landlords. If those losses materialize, and if the banks have to absorb them, it could mean they lack the surplus capital necessary to continue funding a lot of other loans as they heal the damage, pulling even more liquidity out of the residential mortgage market. That could mean that it creates a feedback loop where mortgage rates rise even further and faster; a sort of catalyst reaction that then entrenches these factors more deeply into society and creates bigger problems. That is far from a guarantee but I would argue anyone who is being responsible must factor it into potential long-term scenario analysis if thinking about their own family’s situation.

We Haven’t Even Discussed Other Topics Such as the Consequences for the Value vs. Growth Approach to Investing or Changes in Risk Behavior

Another massive ramification of the change to a normalized interest rate environment is that the forces which caused so-called “growth” stocks to do so well over the past decade – namely, Wall Street applying a valuation model that caused future earnings to be weighted far more heavily than present earnings – naturally reverse. Stated plainly, old-school value stocks such as strong companies with large dividend payouts that have the ability to survive in periods of inflation by passing on costs that consumers essentially choose, or must, accept, are likely to do far, far better in the coming years than they have in the recent past. There are no guarantees, of course, but all historical evidence I can find indicates this is likely to the point society might see an adjustment in multiples with technology companies becoming more affordable long-term and blue chip enterprises getting a bit more expensive.

At some point in the future if rates rise a bit more, it may also become much more popular to buy intermediate and longer-term corporate bonds within tax-sheltered accounts; a trade that has been, for all intents and purposes, severely restrained since I was younger. For example, when I went off to college decades ago, inflation expectations were fairly low and yet you could buy really high-quality corporate bonds at around 8% yields with maturities of 20+ years. I can foresee several scenarios in which this could be enormously advantageous to certain types of retirees, especially when practicing “asset placement” strategies where the highly-taxed corporate bonds are held within the retirement plan accounts and the dividend stocks, Treasurys, and municipal bonds are held in taxable brokerage accounts, essentially arbitraging the tax code. It really expands the number of available tools, so to speak, to build a compounding machine. I’m excited about it.

A big area where things are likely to be much different than they have been is the role of risk. Folks are going to figure out pretty quickly that risk can lead to wipeout. The low interest rate environment of the past made it easy for a tremendous amount of sin and folly to go unpunished. When rates are higher, it is required to be more prudent. Furthermore, the gap between prudence and imprudence grows wider. For example, folks borrowing a lot of money send more out the door to their lenders while people who are net savers suddenly start piling up real cash from their surplus. Psychologically, it seems easier for a lot of folks to be patient and wait for good opportunities if they are earning 4% or 5% on their money instead of nothing. This effectively raises the hurdle rate they demand.

This has been a long time coming. I welcome the return of sanity to monetary policy. I just hope the Fed has the discipline and conviction to see it through to the end rather than reduce rates too soon, or too far.