The Thorne Miniatures at the Art Institute of Chicago Are Incredible

Narcissa Niblack Thorne was born in 1882. She fell in love with her childhood sweetheart, James Ward, and they married. He was the heir to the Montgomery Ward fortune, one of the biggest in the world at the time thanks to a chain of department stores that were once as ubiquitous as Target or J.C. Penney. A graduate of art school, the Chicago socialite wasn’t content to sit around and make small talk all of her life. She began designing and orchestrating these incredible one-foot-to-one-inch scale historical replicas of different architectural, interior design, and furniture styles throughout history to serve as models of how homes and spaces had changed over the years. She was meticulous and insisted upon accuracy (e.g., the wood, down to the grain direction, of the tiny furniture had to be made in exactly the same way as the model piece upon which it was based.)

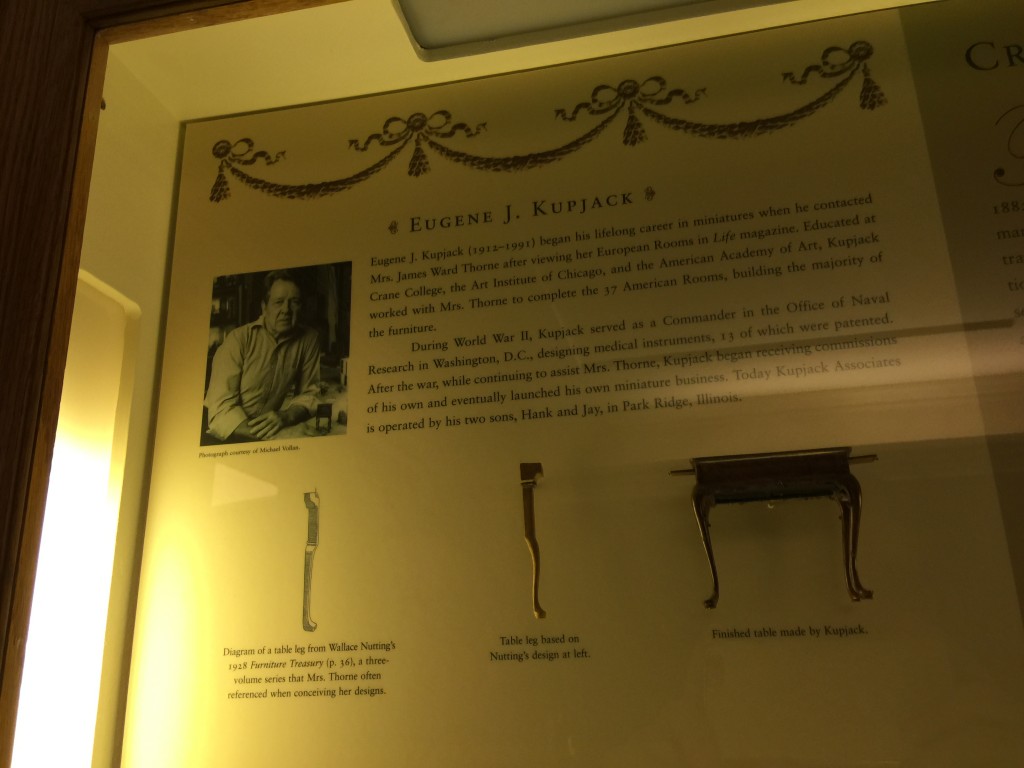

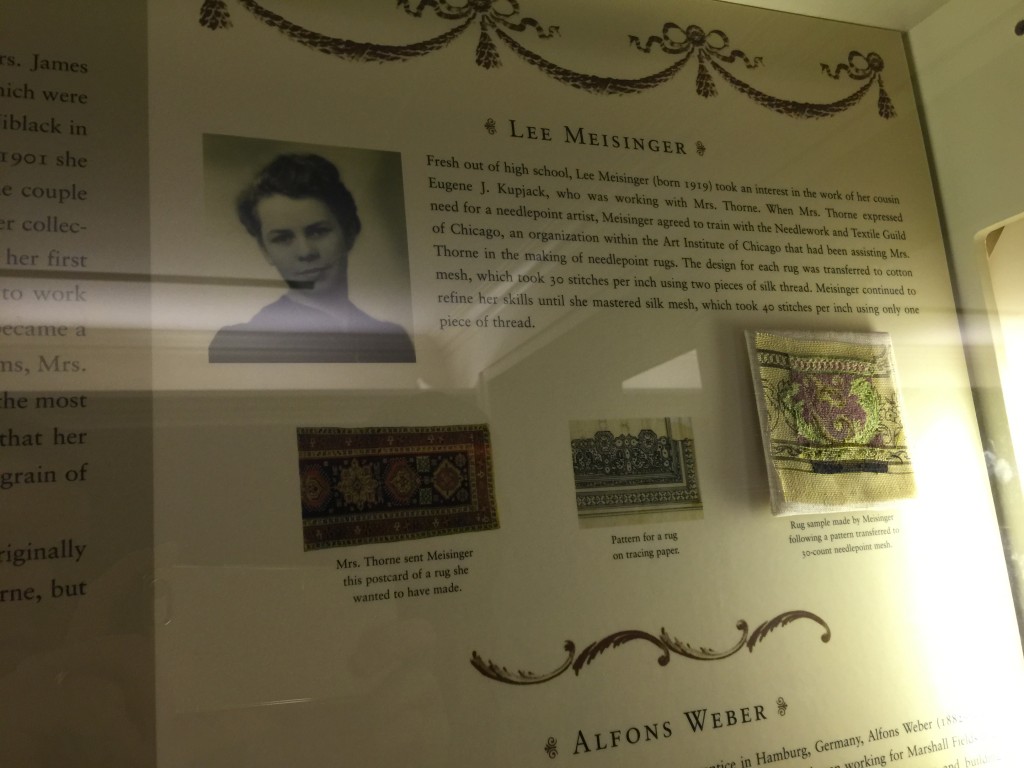

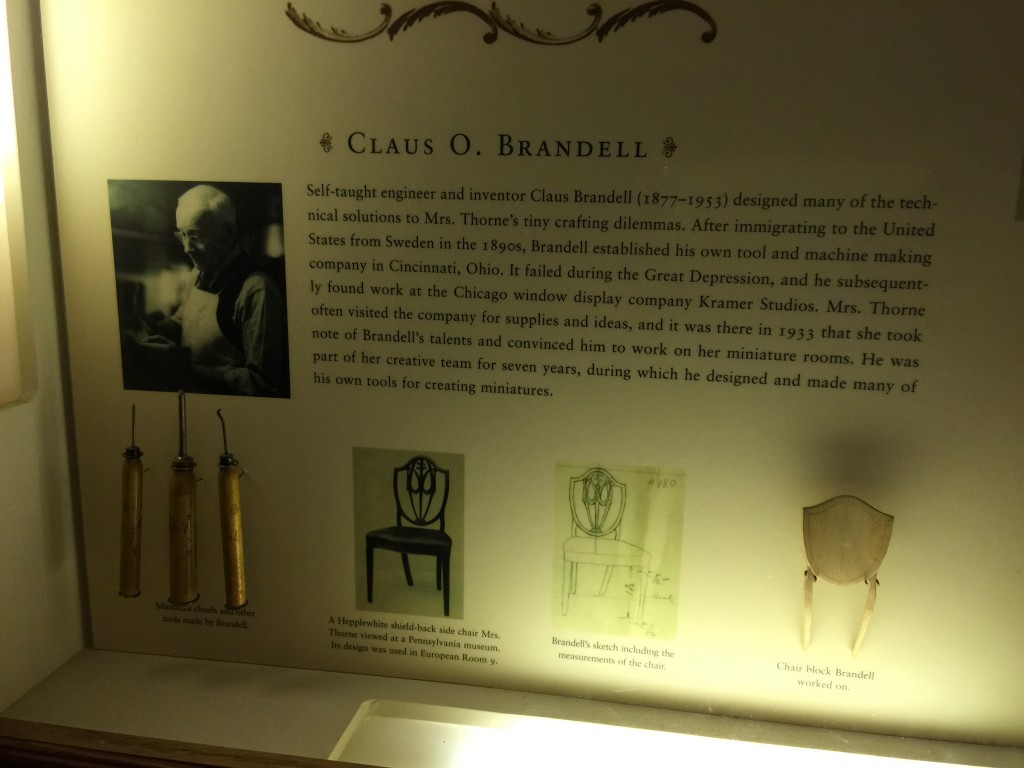

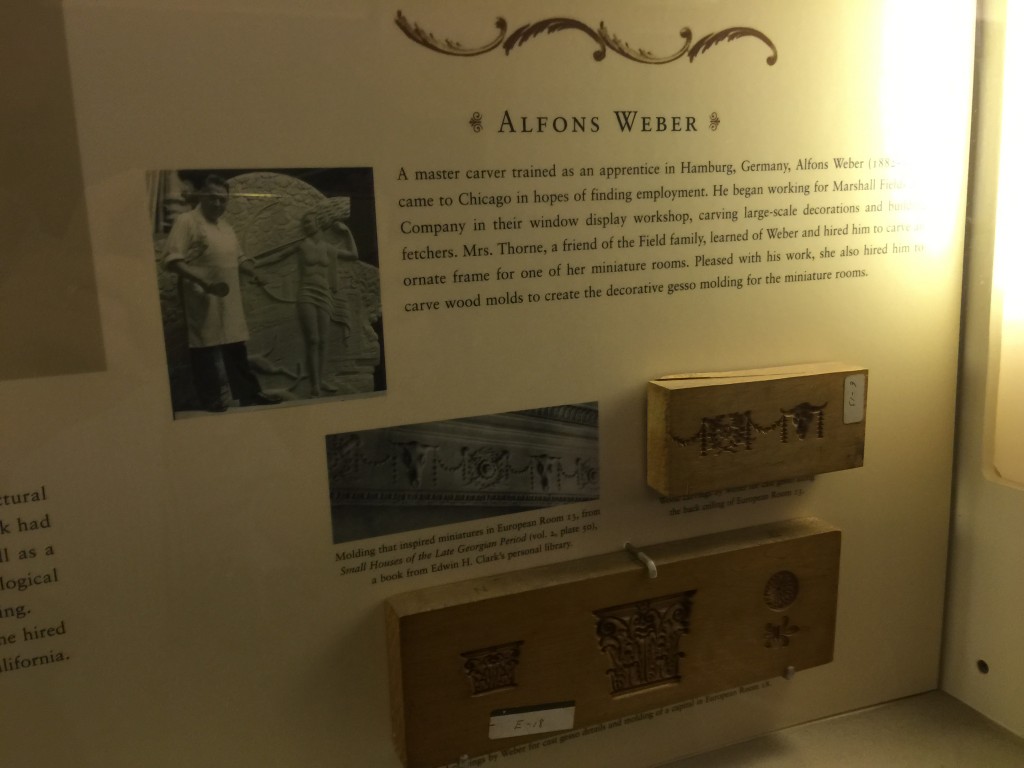

When the Great Depression threw the United States into abject poverty, some of the most skilled artisans in the nation were out of work so she hired them to produce furniture and accent pieces for her project (this turned out to be an interesting case of the economy fundamentally altering art – later, when things had returned to normal, Thorne had to abandon the miniature rooms because she couldn’t find enough people to help her construct her visions). When possible, if she couldn’t find someone to do the work she wanted, she had them educated, going so far as to send one sister-of-a-contributor worker to school to learn a specific style of needlepoint so the woman could product intricate, tiny historical rugs!

Thorne would show off her miniatures at charity events, raising money for non-profit causes. Shortly before she died in 1966, she closed her studio, donated her body of work, and they toured the country in the decades that followed. While she could have made quite a bit of money selling tickets a la P.T. Barnum, she and her family covered the expense of production, kept the craftsman employed during the worst economic collapse in 600 years, and now, her legacy draws in patrons for one of the world’s great museums, helping protect everything from Korean pottery from the Joseon era to famous oil paintings.

After dinner at Tocco last night, we are meeting up with Jimmy to go see the Art Institute of Chicago’s permanent display of Thorne’s miniatures, which he knew I’d enjoy. According to Wikipedia, there are roughly 100 Thorne miniature rooms known to exist in the world, with the Art Institute of Chicago holding 68 of them, the Phoenix Art Museum holding 20, the Knoxville Museum of Art holding nine, the Indianapolis Children’s Museum holding two, and the Kaye Miniature Museum in Los Angeles holding one. The entry on her also states that there is a bar she auctioned off for charity in the 1950’s held at the Museum of Miniature Houses in Carmel, Indiana.

Some of you might remember that I have an irrational, completely not-fully-explainable, totally baffling emotional reaction that can only be described as euphoria when I see perfect miniatures (buildings in particular – like the scale model of the U.S. Capitol Building at Disneyland). It’s like I lose control and get flooded with endorphins to the point I experience pure, unrestrained ecstasy. I gave up trying to figure it out a long time ago but I think it’s the attention to detail and skill required to pull it off; the same reason I am passionate, on a visceral level, about things like Ruffoni cookware, Creed fragrances, Brioni clothes, or Bosendorfer pianos. In a world of mass-produced, cheap, bottom-dollar disposable products – furniture, coats, shoes, toys – knowing there are still men and women who have a craft that took a lifetime to learn, and can create something of lasting value fills me with a combination of admiration, hope, joy, and inspiration. (One of my life goals is to visit Minimundus in Germany, though I’ll probably need to be sedated to avoid total overload.) I was so overcome when I saw the Thorne miniatures for the first time, I reflexively punched Jimmy in disbelief. He joked he was bruised and battered, nursing his arm. It’s as if I lose myself temporarily. I could have probably spent the entire day in the museum if left to myself.

It was a cold, windy, rainy day in Chicago. We made our way toward the Chicago Institute of Art, umbrellas in hand.

Neoclassical architecture … you had me at hello, Art Institute of Chicago. (Though it’s funny I didn’t realize I have such a powerful subconscious association with lions at the entrance of an old building because it seemed wrong it wasn’t the New York Library.)

The Thorne Miniature Gallery was designed to be viewed chronologically (though I didn’t put the pictures in that order). You walk through it to see the evolution of living spaces over the past several centuries.

First, here is a picture for scale so you can understand how the Thorne miniatures are displayed at the Art Institute of Chicago. They constructed the space specifically for the installment and they are arranged chronologically so you work your way around to see how the styles of homes throughout the world have changed over the past 300-500 years.

Let’s get close to one of them … this is the English Reception Room of the Jacobean Period, 1625-55, created circa 1937. Interior measurements 16.25″ x 24.5″ x 19.25″ (41.3 x 62.2 x 48.9 cm). Scale: 1 inch = 1 foot. According to the Chicago Art Institute’s scholarship, “Mrs. Thorne drew on two lavish rooms at Wilton, the magnificent house designed for Philip Herbert, fourth Earl of Pembroke.”

The attention Thorne put into these historically-accurate reproductions makes me feel good about humanity; that there are people out there, with diverse and niche-enough interests, to record, consolidate, produce, store, protect, and display these for posterity is one of the redeeming features of mankind.

Here’s a view of the same English Bedchamber of the Jacobean or Stuart Period 1603-88 but from another perspective so you can see the light streaming in from the windows …

This one reminded both Aaron and me of Tales of Vesperia. Georgian Period English Entrance Hall Circa 1775

English Dining Room of the Georgian Period 1770-90 made circa 1937 … look at the detail through the window.

When her husband died in 1946, the entry on her at Wikipedia says she was left with a fortune north of $2 million to support her. Adjusted for inflation, we’d be talking somewhere between $24 and $30 million using a reasonable approximation; money from her investments generating passive income so she could continue living comfortably and pursue her passion.

Here are some quick pictures of the information of the people who worked with Thorne on her miniatures (click the images to enlarge so you can read about them) …

These were some of my personal images but if you want to see the Art Institute of Chicago’s high-quality, perfect-condition pictures of each Thorne miniature – and there are many, many more – along with information on the details of the particular project, check out the installment page from the museum itself.