The Red Ring Problem – Getting Rich Too Late in Life

This article deals with people who want to be rich. Not just financially independent or reasonably well-off, but actually rich relative to the average American; the folks who want to be able to write a check for a Lexus or live in a nice house, in a neighborhood with great schools, without worrying about it, while watching their net worth climb year after year, decade after decade. The strategy involved for that type of success is slightly different in that it requires you to often build off a foundation that I call your primary economic engine. But I’m getting ahead of myself …

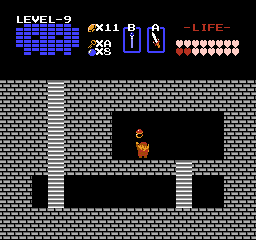

Sometime around 1988, I was in kindergarten. At the time, my favorite video game was The Legend of Zelda. Revealing a quirk in my personality, the challenge of taking something, in this case an adventurer named Link, and building it up to where it was powerful, wealthy, and able to press into new territory, could hold my attention for weeks; months, even. In my heart, I’m a builder. It’s one of the underlying motivations in everything I do. I couldn’t stand that every time you relaunched Mario Brothers, you had to begin at the beginning. To me, it defeated the entire purpose.

The red ring problem, as I call it, is when financial success comes too late in life to enjoy.

One afternoon, as my parents took a nap, I was playing my dad’s saved game slot when I came upon the red ring deep in the recesses of Death Mountain, the final dungeon and home of series antagonist Ganondorf Dragmire, or Ganon, the Prince of Darkness, as he is now known in North America. For those not up to date with Zelda lore, the red ring was a legendary artifact that was the most powerful defense item in the game. It cut damage to ¼ ordinary power.

The problem? By the time you could access the red ring, the game was nearly over. There was only one enemy of importance against which it could be used, and that was Ganon himself. Though it made that final home stretch a lot more comfortable, you couldn’t help but think, “I wish I had this much earlier.”

That general sentiment is a central theme that runs through many of the questions and letters I receive from readers. The “red ring problem”, as I call it, can be summed up as follows:

What is the point of saving money or investing money if I’m only going to get to enjoy it when I’m too old to care?

It is a legitimate concern. Everyone needs an underlying economic engine that provides investment cash for them to grow their passive income.

To Avoid the Red Ring Problem, You Need an Economic Engine

For Ray Kroc, the economic engine was McDonald’s. For Dave Thomas, the economic engine was Wendy’s. For Walt Disney, the economic engine was The Walt Disney Company. For Warren Buffett, the economic engine was Buffett Partners and, later, Berkshire Hathaway. For J.K. Rowling, the economic engine was Harry Potter. For Franke Previte, the economic engines were the songs “Time of My Life” and “Hungry Eyes”. For Miller Gorrie, the economic engine was Brasfield & Gorrie, which was made possible by a block of IBM shares.

[mainbodyad]You cannot think that earning $30,000 per year, raising four kids, and putting a few hundred dollars a month into stocks is going to get you into your dream house or free from financial stress by the time you’re 35 years old. It just isn’t going to happen. You need an engine to drive you there faster. In my case, I used a combination synthetic equity, the creation of intellectual property, and my first e-commerce businesses as the catalysts. Then, at some point after a few years, the cycle became self-sustaining despite the standard of living upgrades I permitted myself to enjoy.1

For highly skilled workers, such as a heart surgeon in a reasonably sized city, the economic engine is the price that he can charge for a unit of time. As long as he is willing to work, he can earn tens of thousands of dollars per month for his family. For all intents and purposes, he can not only fund his retirement accounts, drive a Mercedes, live in a nice home, and take vacations, but he could build a very good collection of assets that generate torrents of cash on their own.

Depending upon how frugally our doctor is willing to live, he could find decent real estate properties, such as storage units, pay cash for them, and target a 10% return on his money. Suddenly, he’s not only a full time doctor, but he’s earning $60,000 a year from a $500,000 storage unit collection he owns off a nearby highway. As long as he avoided doing something stupid, he should end up very, very rich relative to the average American without anyone knowing. It would not be unreasonable for a well-paid surgeon who began young enough, stuck with it for 40 years, and was reasonably good at managing his assets, to reach a point where his holdings threw off more than $100,000 per month before taxes. The best part? He would have done it while wearing cashmere sweaters, flying first class, and spending weekends in Paris along the way.

Some people don’t need an economic engine because they don’t mind the red ring problem. These are your Millionaire Next Door types; the folks who live comfortably but don’t want expensive things. For them, as long as they have no debt, plenty of cash in the bank, a quiet, enjoyable life, friends, family, and a job they love, they are ecstatic. The purpose of watching their net worth expand is the fun of seeing something grow, much like gardening or collecting, while knowing the money will eventually be a blessing to others in the form of inheritances and charitable donations. This is a perfectly admirable, respectable, and to-be-emulated way of living for most of the population.

What Counts as an Economic Engine?

I think a good definition of an economic engine is any asset or skill you acquire that allows you to earn surplus investment cash equal to at least what the median American household earns, which is between $48,000 and $50,000 according to the latest government figures. That is, if you own an ice cream parlor that makes $50,000 pre-tax, and you saved and reinvested all of that into other assets that threw off cash, it is the equivalent of having a median American household saving 100% of its earnings. That’s a major tipping point.

Figure out what your economic engine is. Don’t wipe yourself out trying to get it, either. That is a mistake I see a lot of people make. When Aaron and I started our first business, we kicked in something like $3,500 between the two of us. We didn’t go to the bank, put our entire lives in hawk, sign over our investments as collateral, and risk everything we had.

This is another way of reminding you to avoid wipe-out risk. If you need to take on high levels of risk to be successful, you’re not being smart enough. Whatever economic engine you build or acquire, do it in a way you’ll survive if the stock exchange were shut down for a few years and the economy went into a prolonged depression. I’ve heard horror stories of well-meaning men and women who mortgaged their homes to launch Beanie Baby retail stores. There is nothing worse to have not only failed, but to then have that failure take out your past successes. Isolate your projects so if once collapses, the others aren’t harmed. In engineering, these backup systems are known as redundancy. You need to build redundancy into your financial life over and over and over.

1. There is a notable exception to this rule. If you begin young enough, as I explained in a recent article, you could reach your mid-thirties with a $250,000+ portfolio of high-quality, blue chip stocks. This could then serve as a source of cash dividends, equity, or backup liquidity to accelerate whatever other projects you had going on in your life. Stocks are merely one mechanism for building wealth. They are a way to inventory profits and take advantage of opportunities to become a partial owner in businesses run by other people. In our case, we consider investing in stocks an important part of our strategy. I would not be content if I were a teacher, with no other source of income, buying $100 worth of General Electric every month. That is because I don’t want to be merely financially successful. I enjoy being rich.