Personal Thoughts on Passing Wealth to Children and Grandchildren

I’ve been thinking about the next 25 to 50 years; mapping out plans for my personal life, my family, the firm, and, to some degree, certain societal changes that I think are important and worthy of significant political and financial investment. Among the major decisions Aaron and I will need to make:

- How much wealth do we give each of our future kids (and, as a separate matter, our future grandchildren)?

- How do we structure that wealth? How can they access it? What are the conditions? What is the timing?

- How do we protect that wealth from others? This includes both intentional and non-intentional damage to the family fortunes. For example, what if, decades from now, one of our future children were married with children of their own? Then, God forbid, our child dies. The surviving spouse gets remarried and the assets aren’t properly structured. The surviving spouse then dies. It is possible the second spouse in this scenario ends up walking away with a major portion of Kennon-Green family capital along that particular branch of the family tree. This is not acceptable. (Fortunately, the scenario I just described is solved easily enough – it’s one of the more routine matters in the wealth management industry – but it’s important to try to work through nearly every disaster situation imaginable to identify weaknesses.)

- How do we maximize the compounding advantage? For example, through the use of intelligent tax strategies or other mechanisms, how can we add return above and beyond what otherwise might have been possible which, over long periods of time, can make an exponential difference in capital accumulation and preservation?

- How can we plan for a series of contingencies that are presently not knowable? For example, going back to an earlier point but taking a different approach, what if, God forbid, I were to pass away before the end of my life expectancy? What about Aaron? Both of us? One or more of the kids? Even though the probabilities of this are exceedingly small, I would very much prefer that we be the ones who provide a practical framework for the disposition of assets even in remote-contingency scenarios rather than defaulting to so-called “rules of construction” or intestate succession procedures crafted by one or more state legislatures. Furthermore, I would prefer nearly all of this be done with absolute discretion so that nearly nothing is public record. There are many reasons for this ranging from a desire for privacy for our heirs apparent to a defensive strategy in the event of a Black-Maned Lion Debacle. (Several months ago, I’d randomly question Aaron with outlandish scenarios – usually, at 3 a.m. as we were supposed to be asleep in bed, because I was turning over situations and potential outcomes in my mind – e.g., “If that were to occur, would you prefer for [x] or [y] to happen?”.)

What makes it somewhat tricky is that all of these things tend to involve inter-connected trade-offs. For example, certain trust strategies that can provide greater asset protection mean giving up more control and/or potentially paying higher taxes. Fortunately, we had already put a lot of thought into some of the basics as you might remember from the stream of trust fund posts a few years ago so we had a general idea of what our thoughts were on these matters. The process has re-ignited now that we are settling in California and ready to overhaul both our estate plans and long-term strategic plans, all of which now need to change by virtue of the fact we are relocating here for what we expect will be many, many years.

A Side Note on Working Through Complex Problems

When I work through something like this, I tend to begin by writing out a high-level overview of the matter. This allows me to organize the concepts into categories or blocks that I can then, later, mentally reorder as I create a roadmap for how to proceed in a logical, structured way designed to help minimize oversights. Usually these notes take two forms:

- Specifically identifying what I am trying to accomplish, who is going to benefit, and why I am doing it (the latter requiring me to be very clear about my my motivations and/or intentions); and

- Specifically identifying how and when I am going to accomplish it.

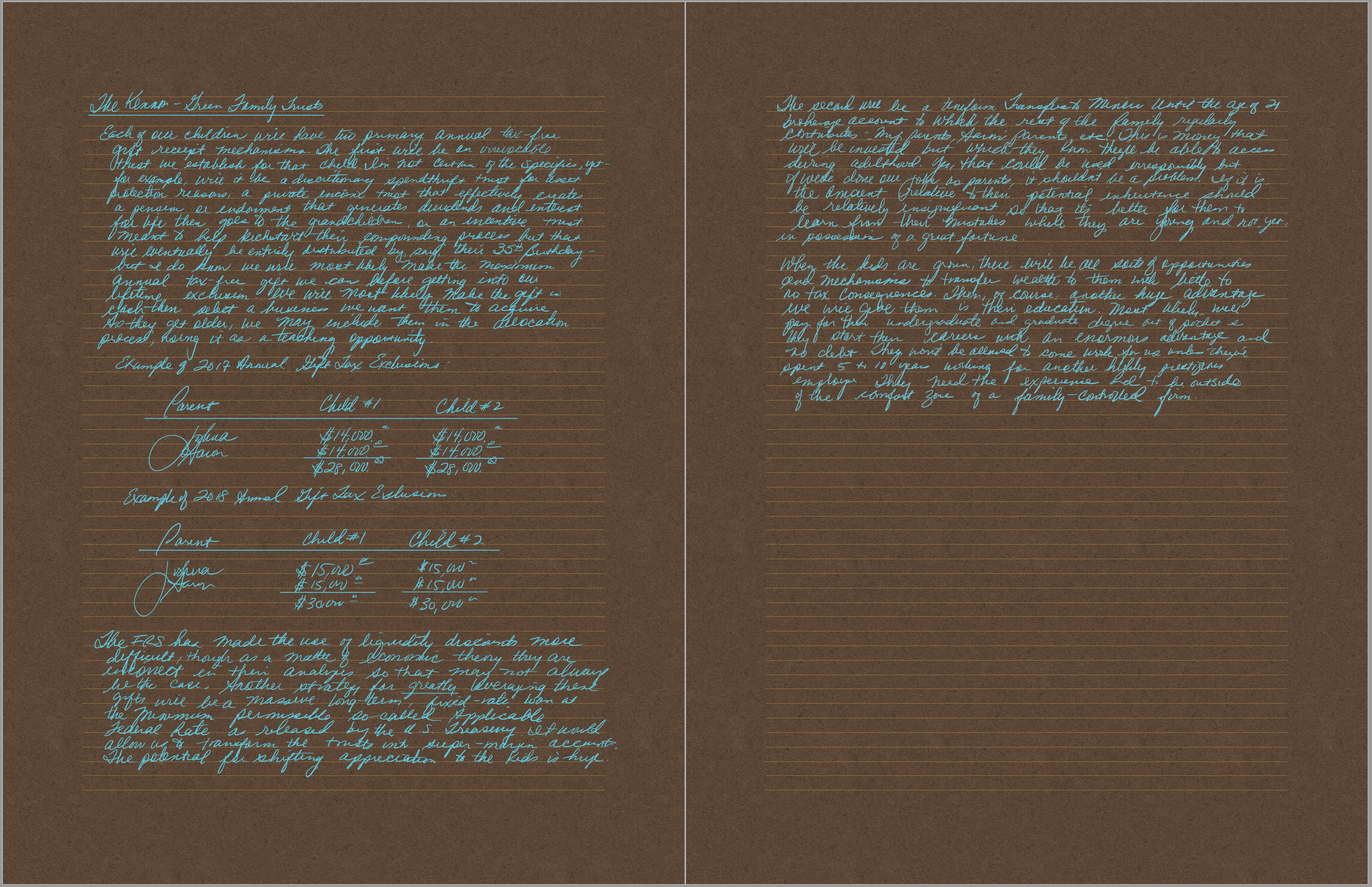

As a matter of policy, I tend to always begin with the first item. Everything else risks derailment if I am not crystal clear on what I am trying to accomplish and the reasons I am doing whatever it is I am doing. The latter stages are more brainstorming exercises that get refined into action plans; e.g., in regard to the portion of the plan that involves transferring wealth to our future kids and grandkids, my early-stage notes look like this:

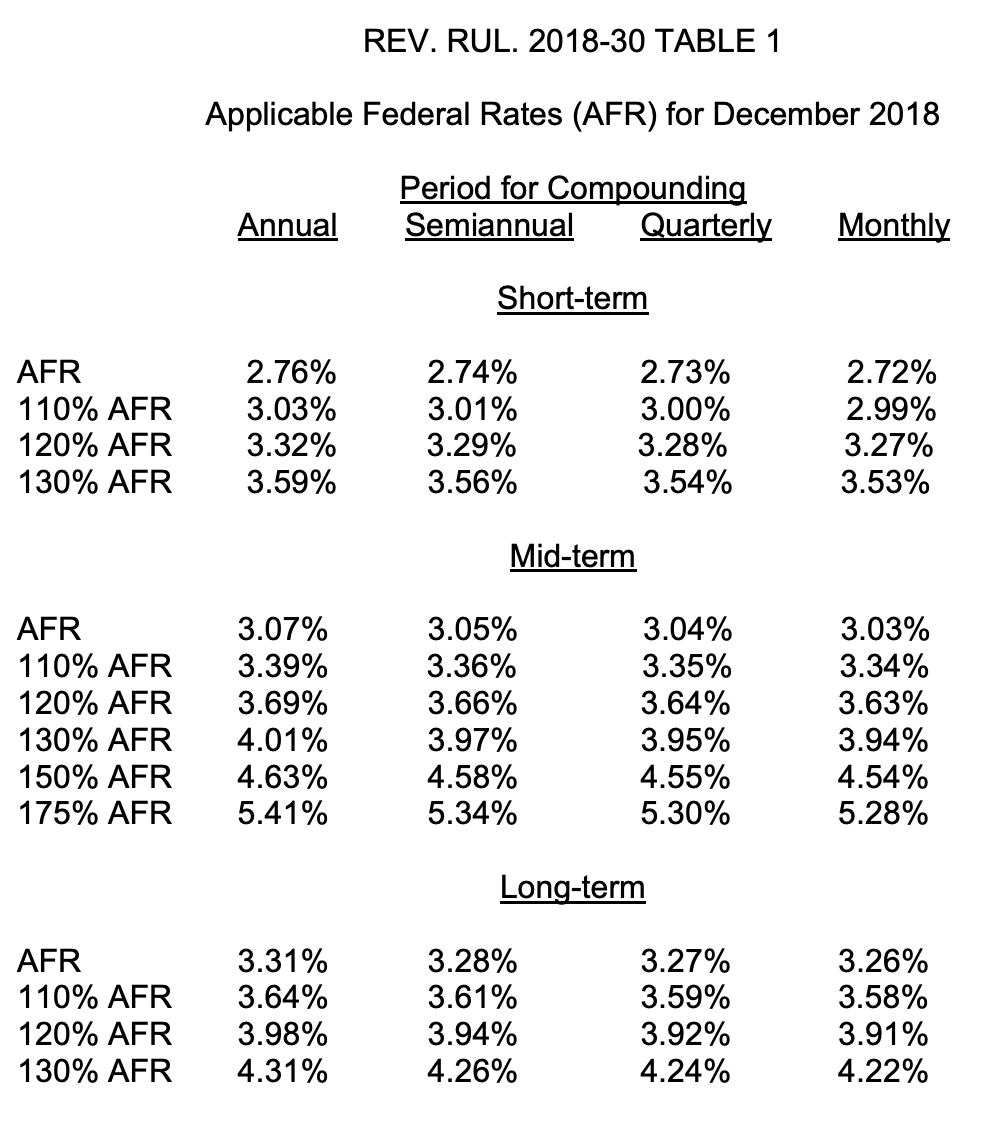

It was a way for me to begin the creative process; to find points from which I can branch out to other areas that I might want to explore. For example, in this situation, it caused me to think about how to exceed the annual gift tax exemptions without using the lifetime exemptions or, in some cases, after they have already been exceeded. There are ways to do that. One is to create a business entity capitalized by the various family members then underwrite a privately placed note to the entity itself, charging an interest-only loan at what is known as the “Applicable Federal Rate”. These rates, which are published by the IRS monthly as revenue rulings, are the minimum interest rates that can be charged between related parties without incurring potential gift taxes (I’m oversimplifying here but that’s the gist of it for the purposes of this discussion). For December 2018, here is what the fixed-rate charts look like (see below). Note that, for the AFRs, short-term refers to anything less than 3 years, Mid-term refers to loans made with maturities of 3 to 9 years, and Long-term refers to loans made that don’t mature for 9 years or more. These interest rates can be fixed at the AFR then in effect at the time the initial loan was made.

An illustration might help. Keep in mind there are countless ways someone might approach the task so this is by no means a blue print given that it would need to be tailored to the specific situation and what was trying to be achieved. That said, imagine you had a family with two parents and three kids. The family capitalizes a new limited liability company with $10,000.00 by issuing two voting classes of membership units.

- Class A membership units – 10 membership units outstanding @ $100.00 per membership unit = $1,000.00 initial capitalization.

- Each parent owns 5 of the membership units.

- Each membership unit is entitled to 25 votes.

- Each membership unit shares proportionately in gains and losses with both Class A and Class B membership units in the aggregate.

- Class B membership units – 90 membership units outstanding @ $100.00 per membership unit = $9,000.00 initial capitalization.

- Each of the three children owns 30 of the membership units

- Each membership unit is entitled to 1 vote.

- Each membership unit shares proportionately in gains and losses with both Class A and Class B membership units in the aggregate.

At this point, you have a situation where the parents control 73.53% of the voting power (the Class A membership units can cast 250 votes as a class, the Class B membership units can cast 90 votes as a class, for 340 votes total) but only 10.00% of the equity. This means that 90.00% of the gains and losses will go to the kids. This is by design for the next stage: the family now holds a vote that, for various reasons, should be unanimous. This vote authorizes the company to issue a privately-placed, 50-year bond to the parents. To demonstrate how extreme the leverage can be, let’s assume the bond in this illustration is $30,000,000.00. (In the real world, the parents may want to build in some protective measures for themselves. There are different ways this could be done but you’d have to be aware of the trade-offs. For example, you might put in a trigger that, upon default, the bond becomes convertible to equity at the option of the parents. On the other hand, you might want to avoid a so-called “demand loan” that allowed the parents to require immediate repayment at any time because that would then require that the AFR be reset semi-annually, losing the advantage of fixing in the interest rate for the next half-century at an incredibly low rate.) The interest rate is set at 3.31% per annum, the AFR for annual compounding in effect at the time.

What the family has now done is create a super-margin account for the children’s benefit. The company is going to owe the parents $993,000.00 in interest each year for the next 50 years on that borrowed capital but any returns above that rock-bottom cost of capital, 3.31%, are going to go to the equity ownership, of which the children hold 90% proportional interest through the Class B membership units. At maturity, the par value of the bond, $30,000,000.00, will need to be returned to the parents and/or their estate. (One interesting twist: the parents could give their Class A membership units to the kids as an inheritance, and the bond to a charitable organization to support their philanthropic goals while further lowering their tax bill. The kids would gain all of the equity and voting power. The charity would get the stream of interest income for years plus the bond maturity value.)

To demonstrate: let’s say that in first year, the $30,010,000.00 in initial capital – $30,000,000.00 from the bond, $1,000 from the Class A membership unit capitalization, and $9,000 from the Class B membership unit capitalization – earned 10.00%. The pre-tax gain would be $3,001,000.00. After paying $993,000.00 in interest expenses to the parents, there would be $2,008,000.00 remaining. This would be divided equally amount the 100 membership units outstanding, giving each a $20,080.00 pre-tax profit allocation. As a result:

- Parent 1 – Earns $596,900.00 from the company through two sources:

- $100,400.00 pre-tax profit allocation (5 Class A membership units x $20,080.00)

- $496,500.00 in interest income from his or her bond

- Parent 2 – Earns $596,900.00 from the company through two sources:

- $100,400.00 pre-tax profit allocation (5 Class A membership units x $20,080.00)

- $496,500.00 in interest income from his or her bond

- Child 1 – Earns $602,400.00 pre-tax profit allocation (30 Class B membership units x $20,080.00)

- Child 2 – Earns $602,400.00 pre-tax profit allocation (30 Class B membership units x $20,080.00)

- Child 3 – Earns $602,400.00 pre-tax profit allocation (30 Class B membership units x $20,080.00)

Remember that each of the children bought their 30 membership units (90 combined) for $100.00 each, or $3,000.00 per child ($9,000.00 combined). That means each of the kids just earned $602,400.00 pre-tax on a $3,000.00 investment. This shifted the realized gains, unrealized appreciation, and income out of the parents’ estate into the kids’ hands, by-passing the estate tax down the road. Over time, the consequences should be enormous. In essence, the parents are renting their capital to the children at rock-bottom rates, allowing them to arbitrage the difference between the return earned on those assets and the cost of capital. This allows for the $3,001,000.00 in gain to be divided so that $1,193,800.00 goes to the parents and $1,807,200.00 to the children. Over time, and especially if interest rates rise, estate tax limits decline, estate tax limits rise, and/or the returns on capital earned by the business are particularly good, the economic purchasing power moved from one generation to the other could be enormous. As the decades pass, it’s not hard to end up with mathematical scenarios where the kids walk away with hundreds of millions of dollars, not a penny of estate or gift taxes being paid on it. Again, I’m somewhat oversimplifying here – things like this can require a tri-party team of management (including outsourced asset management), attorneys, and tax accountants to evaluate the unique circumstances of a given family and/or individuals, as well as the ever-changing rules, regulations, and laws that must be navigated – but the music remains the same even if the lyrics change. That is the heart of the game if you are looking at it objectively – transferring purchasing power from one generation to another in a way that by-passes estate and gift taxes.

Writing this out just brought up a question in my mind. I need to find an answer. Imagine you held a large, concentrated position of highly appreciated stock in a business. You were fine selling it to diversify but, in the meantime, could you loan the stock to a child, maybe at the Applicable Federal Rate, and allow him or her to write covered calls against the borrowed shares, essentially shifting the investment gain to him or her so they could pocket the income? If the annualized premium income from the options exceeded the AFR by a material rate, that could add up quickly. Obviously, you’d need enough liquidity in the derivatives market of whichever particular security was involved but … I think an intelligent person could probably do something with that unless there is a loophole closed somewhere. Even then, is it really even a loophole given the economic reality of the transaction? I don’t think so. Huh. That is … interesting.

This is one of the things that makes capital allocation so enjoyable. Real estate investors, in particular, have lots of options not open to other investors. A family that held apartment buildings, office buildings, or industrial buildings could separate the ownership of the land from the building themselves, transfer the land into trusts for the kids and grandkids, then sign lease agreements with the trusts so the buildings were paying the ground rent. Wealthy families with the ability to redirect hundreds of thousands of dollars per year, per child could structure businesses in a way that allowed their older children to indirectly contribute up to $60,500.00 every year to a Roth IRA. When founding a particularly promising start-up, ownership can be given to the children at nearly zero cost, shifting the appreciation and income to their estate. I could go on but the point is, the number of potential tools available is legion. Some will work for certain families and certain times, some won’t. It all depends upon the individual circumstances at the time as well as what the parents want to achieve.

I’m now sidetracked. Time to get back to the main topic.

Deciding What We Will Do for Our Children and Grandchildren

While the plan is a work-in-progress, there are several things we do know for certain. This meant throwing out the assumptions we had growing up, and the things we were taught, and re-evaluating conditions as they are today. As a result:

- We intend to make significant investments in education – Effectively, there will be no practical limit to the resources we are willing to devote to each of the kid’s educations, including everything from music lessons and summer camps to international travel and paying for both their undergraduate and graduate degree(s) in order for them to emerge with a massive life advantage including being debt-free. Very few other capital outlays can put a glass floor beneath a family the way an education can. The United States, and much of the world, is now more of a meritocracy than it has been at any time in history with inherited wealth representing an ever-shrinking portion of wealth accumulation. Along with learning how to think critically, helping the kids develop their human capital so they can sell their labor in favorable conditions at significantly above-average rates, and to emerge from that development without the weight of student loans, is one of the biggest, and easiest, wins we can provide as parents. No other dollar we spend is going to have the same long-term positive influence.

- We intend to set them each up with a non-profit foundation – At least in the beginning for privacy and ease reasons, we may structure these as donor-advised funds, but we want the kids to understand that part of good citizenship means building the civilization to benefit others. By making them responsible for allocation decisions – Who is, or which causes are, worthy of getting money? How much do you give? How do you balance current needs with future compounding? – we can help them learn to think through complex questions, preparing them for adulthood. We may have them devote a portion of all of their income from allowances, labor, and investments to charitable giving, too, to create the habit of thinking beyond one’s self.

Going further, there are still questions we need to answer. Some have no right or wrong answers but are, rather, a matter of personal philosophy about what is the fairest way to behave; e.g., do we structure inheritances using English Per Stirpes (aka Strict Per Stirpes), Modern Per Stirpes (aka Per Capita with Representation), or Per Capita at Each Generation? Others involve trying to decide how comfortable we are with parting with capital prior to knowing the ultimate use of that capital; e.g., do we maximize the annual gift tax exemptions even though doing so means a good deal of money is transferred in the decades prior to really seeing how our children develop as people? (As a quick refresher, before dipping into the lifetime exclusion amounts, an individual can gift up to $15,000.00 per annum to another individual without paying gift taxes (as of 2018 with annual inflation adjustments made from time to time). In the case of a married couple, that means it is possible to gift $30,000.00 per annum, tax-free, to each child.) If we do, those irrevocable gifts might be structured in one of three ways:

-

- We establish an irrevocable trust into which we make the maximum tax-free gift each year, investing the capital for the child. The major question for me is whether or not they receive access to the principal or whether we structure it as an equitable lifetime interest in the income of the trust so that, effectively, they enjoy what amounts to a private annuity. We will probably continue these gifts for the entirety of our lifespans.

- We gift shares of a family holding company outright, maintaining effective managerial control but intending, over time, to turn it over to them as their own enterprise.

- We establish a UTMA, maturing at the age of 21, into which all other family members can contribute regularly, similar to the UTMAs that I worked on setting up for our nieces and nephews. That way, the kids have a decent chunk of change turned over to them upon reaching adulthood, while allowing us to see how they handle it; a sort of test case for much, much larger figures down the road.

One possibility is to have individual trusts, as well as larger so-called Dynasty Trusts, both working in conjunction, with the latter intended to be a sort of multi-generational family endowment. Properly done, this would put the principal beyond the reach of the kids and grandkids, but more importantly, any of their potential spouses, step-children, creditors, and/or any one else who might see them as a source of largesse.

Pitfalls in Wealth Transference to Avoid

The nice thing: the thought process about multi-generational wealth planning is made easier by knowing which things to avoid. In both life and business, knowing what not to do is often as helpful, if not more so, than knowing what should be done.

For example, the easiest way to rip a family apart, ensuring your children and grandchildren not only stop speaking, but hate each other with a seething passion, is to leave a smaller inheritance to the “successful” child(ren), increasing the amount that goes to less affluent child(ren). People want to delude themselves into thinking they, and their family, are somehow the exception but it remains among the most foolish ways to behave because in nearly every case, even if a person doesn’t think it will, it ends up breeding resentment, coming across as punishing success; that the child(ren) who did everything right are being discriminated against because they worked hard, they were responsible, and they planned their future. Sometimes even on a deeply subconscious level, money, rightly or wrongly, is seen as an expression of love or approval. It’s human nature. It’s primitive and deep. Plus, the capital that would have been split evenly could have gone to the successful child(ren)’s own child(ren), perhaps placed in trust. In this case, those grandkids are punished in real and tangible ways because their parents were successful.

Consider an anecdote shared by an estate planning attorney named Jeffrey Condon when he recounted an experience with a client:

Mr. and Mrs. Wayne have two children. Their son is a successful medical doctor. Their daughter and her husband are employed but have difficulty making ends meet.

After a great deal of thought, the Waynes decided that because their daughter had a greater financial need, they wanted to leave 75 percent of their money and property to her and only 25 percent to their doctor son.

“Mr. Condon,” said Mrs. Wayne with all confidence, “we believe this plan will achieve economic justice between our children. After all, our son doesn’t need the money, but our daughter does.”

Good plan, right? Wrong! They had forgotten to consider what their son would think.

“Mr. and Mrs. Wayne,” I responded, “unequal economic circumstances do not justify treating your children unequally. Sure, your daughter will be happy, but your son will be resentful. After both of you die, this plan may create a rift between your children—and they may never speak to each other again. And what’s more, this conflict may transcend to your grandchildren.”

The Waynes were very upset with my response. They were absolutely convinced their plan was right and nobody, not even the lawyer, was going to change their minds. And they let me know this in no uncertain terms.

“Mr. Condon, our children love each other,” said Mr. Wayne in a harsh, adamant tone. “They would never let money come between them. They would never let money get in the way of family loyalty. Besides, this is our money and we can do whatever we want.”

I could feel the Waynes’ resentment of me growing by the second. But having seen what happens between children who are left unequal inheritances, I just could not stop myself from further comment.

“You are correct, Mr. Wayne. It’s your money and you can do whatever you want. But let me put it this way. Pretend you are your son. In high school, you worked diligently to get good grades and were rewarded with a college scholarship. During college, you strived for high marks and worked part-time so you could enter medical school. Ultimately, you graduated college, graduated medical school, and became a successful doctor, bringing joy and honor to your parents.

“How would you feel, Mr. Wayne, if after achieving all this your parents left you less because you were successful? I’ll tell you how you would feel. You would be hurt and angry. You would feel your parents had punished your success. And if you talk with your son about your plan, he would tell you the same thing.”

The Waynes were unimpressed with my hypothetical situation. They stood up, said they would get back to me after talking it over with their son, and abruptly walked out of my office. I, however, knew they would not return. They would find another attorney who would not question their inheritance plan.

A few hours later, Mrs. Wayne called me. The tone of her voice was no longer bold. It was sad. She and her husband had spoken with their son about their plan and were vastly disillusioned with his response.

Her successful son, she told me, was enraged with the idea that he would inherit less. “How could you even think of doing this to me,” the son yelled at his mother. “I worked so hard for you. I studied when you asked me to study. I made something of my life. And now you want to punish my success.”

Most parents want to do the right thing for their children and make them happy. And, naturally, parents want to help the child who they feel needs more help. But the successful child’s argument is hard to refute. Why should his parents punish his success and reward his sister’s failure?

(In addition, the economic disparity between children may change. The successful child could experience a reversal of fortune due to ill health, bad investments, divorce, remarriage, or for any other reason. And the needier child may someday climb the ladder of success.)

Mr. and Mrs. Wayne’s perception of their “perfect and loving” children had been shattered. For the first time, they realized family love did not transcend the division of money. With their son’s shrill voice still resonating in their ears, the Waynes reconsidered. In their inheritance plan, they left their children equal inheritances.

After Mr. and Mrs. Wayne died, I had the opportunity to speak with their daughter. She told me she was still “needy” and could have used a larger inheritance. But she agreed with her parents’ plan. If she had inherited more just because she needed more, her brother, whom she loved dearly, would have never spoken to her again.

Put bluntly, if one of your kids starts a software company and is earning millions of dollars a year, and another works for a non-profit, the portion of the estate you are leaving to them should still be divided evenly. To do otherwise is to beg to have your family destroyed. It is a profoundly dumb way to behave and, should you decide to proceed despite all of the warnings and wisdom to the contrary, your family will reap the consequences of the folly you’ve sewn.

When might non-equal inheritances be justified? What extreme cases can make this defensible? Leaving aside the matter of so-called “incentive trusts”, which are designed to reward good behavior as well as major life accomplishments and are mentally seen as different because there is the matter of choice attached to the payout and the payout is open to all children creating an appearance of fairness, this is most pressing in situations where one or more of the kids is a total screwup. Then, I’ve only seen two things work:

- Putting their portion in a trust that doesn’t allow them to access the principal, only later disbursing the funds to their children (your grandchildren) or having it revert to the other siblings in the case of death, such as from a drug overdose. This means they will be able to pay for food and rent. You can even have it tied to a requirement they have to remain sober for a certain period of time before distributions start, again.; or

- Accepting that the family is irreparably torn and disinheriting the failure. This has the effect of concentrating the capital in the “successful” line of the family tree. This choice is drastic because people can, and do, change – what if someone were addicted to drugs for years in their youth but then got clean and lived a productive life? – but if the goal is preservation of the family’s wealth, it can be a coldly logical, if not arguably cruel and ruthless, choice.

Relatedly, Aaron and I have toyed with the idea of giving our children their inheritances during their lifetime so they know the bulk of our remaining estate goes to charity. I’m not sure where we’ll end up on that matter but it’s an intriguing idea.

The Relationship to Wealth Changing Over Time by Generation

Finally, I’ve noticed an interesting change in my own psychology over the past few years. For better or worse, Aaron and I have begun to understand the way older wealth behaves. We earned our capital and we are proud of that fact. I love finance as both a science and an art – my idea of happiness is a good reading chair, a pile of annual reports, and a cup of hot, black coffee surrounded by friends and family who are playing games, making dinner, or generally being nearby – and can talk about it endlessly with anyone who is even remotely interested. I’m passionate about it. I like complex problems. I like finding solutions. I like the joy of watching something you’ve nurtured grow. I approach the compounding machine Aaron and I have assembled, and, now, the compounding machines we are assembling for the private clients at our asset management firm, the same way a gardener might look at his garden. Still, when I think about our kids … I don’t necessarily want them talking about money with anyone else so people learn to like them for them, not their wealth. Even more surprising: I understand the temptation for them to date and marry within a social class of other people who will also be well educated and have trusts because it eliminates a source of stress; worry about whether the capital that we have worked so hard to attain and protected so fiercely is going to be threatened by an outsider. I understand wanting a house that isn’t publicly listed anywhere, bought through an anonymous trust or limited liability company and that isn’t visible from the street.

Thinking about how much information I used to have on this blog and my old About.com site it’s fair to say the level of disclosure I offered in my early twenties occasionally makes me me deeply uncomfortable when I run across it. Yet, when I was younger, it was precisely that sort of candor that I found helpful in my own journey. It’s a double-edged sword. Maybe this is one of the reasons I like working at Kennon-Green & Co. so much. There, I’m dealing with people who have their cards on the table and who are known to me. They are trusting us to treat their wealth with the same respect and care we use for our own. The structure creates a situation in which I feel I can be far more candid than I can be on a public blog if we are discussing topics. I believe that part of it, too, is the political environment. Aaron and I instinctively withdrew a couple of years ago to focus on preparing ourselves for what we believe was, and is, coming. (Early in my life, I did a case study similar to the Dolly Parton case study I shared, of RuPaul Charles. As I’ve updated it over the years, I remember him once talking about how cultures tend to go through periods of opening and closing, sort of like the mechanism of breathing, the rib cage expanding and contracting. So much of getting ahead is figuring out how to position yourself so you aren’t working against that transition from an open, curious, and loving environment to one that is insular, defensive, and cruel. You have to pick your moment; when your efforts can have outsized rewards that are exponentially higher for the same amount of work.)

Header image licensed from Adobe Stock