I Can’t Seem to Stop Myself from Buying Nestlé

I spent the past few days updating some of my own internal case studies, spreadsheets, and other documents, as well as wrapping up a few things that needed to be crossed off the agenda for the private businesses. I ended up putting together a collection of visual references covering some of the long-term holdings I keep for my household, among them Nestlé SA following my post on Monday. After looking at it, I realized I was being a complete fool by not buying more so I placed a second order on Tuesday and threw more shares into the portfolio.

Few times in a lifetime will one find a business like this. Few times in a lifetime can one say with relative certainty that it is at least trading at or below fair value, which appears to be the case at the moment. Given that I neither care about market fluctuations, nor the currency variability between the U.S. Dollar and the Swiss Franc, nor the fact the dividend is paid only once per year, my reluctance to buy more makes no sense. If the stock market collapses tomorrow, I’m willing to bet that I’ll still be happy over the next 25+ years at the prices I paid this week. Nestlé may not make sense for everyone, but for my particular situation, I should be locking more in the proverbial vault.

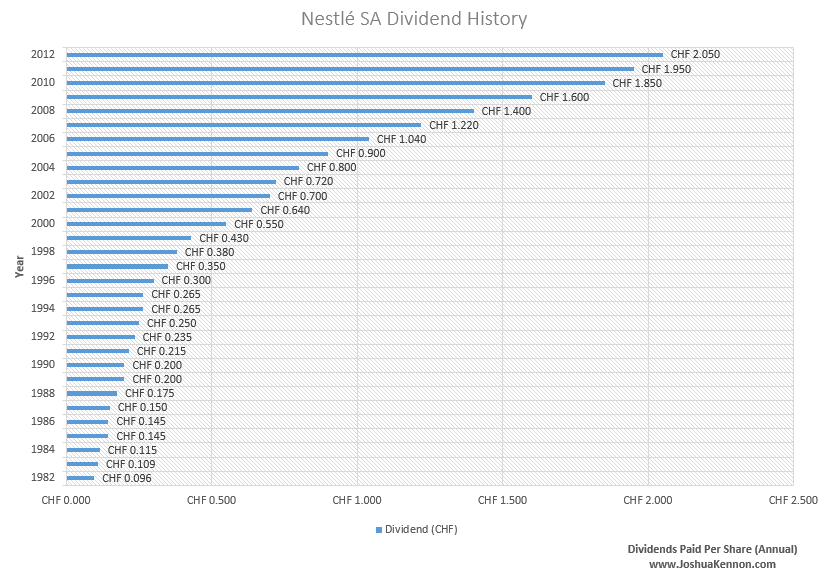

The ability of the firm to generate surplus returns on capital employed is just staggering. It shows up in the earnings and dividend record. One metric will illustrate this: When I was born, a single share of Nestlé paid its owners an annual cash dividend of CHF 0.096. As profits grew, so too did the money mailed out from those profits in the form of cash dividends to owners. For the next 30 years, the average compounding rate for the dividend was a bit more than 10.7% per annum, thanks to the food and beverage company’s ability to raise prices, launch new products, buy back its own shares, and fund acquisitions. This meant by the end of the period, your most recent dividend had reached CHF 2.05. Over the entire 30 year period, your annual payouts had grown by 2,135% without reinvesting a single one of those dividend checks (had you done so, your income would have been even more impressive and compounded at a much faster rate).

While you waited for this magical compounding machine to grow, you received cumulative cash of CHF 19.445 for every share you owned. That is money you could have spent, given away, invested elsewhere, or put into savings. As long as you never got rid of your ownership stake, as time passed, you were sent more and more money, the checks growing at a rate far in excess of inflation.

Look at it visually. This chart encompasses multiple wars, several recessions, the 1987 crash, the dot-com bubble, the savings & loan crisis, the Asian currency crisis, the September 11th terrorist attacks, the real estate bubble, the greatest economic collapse since the Great Depression, countless changes in the tax code, wildly different interest rate environments, and five U.S. Presidents serving nine terms. How can you care what the stock price does in a given year as long as your initial purchase price was attractive? All you have to do is sit down, be quiet, and collect your checks. That’s a wonderful first world problem to have.

It was an ordinary occurrence nearly every year on that chart to watch your shares of Nestlé rise or fall by 30% or more as buyers and sellers negotiated among themselves for what they were willing to pay for a piece of the company at any given moment. To the long-term owner, it meant nothing unless you wanted to take the opportunity to buy or sell more ownership. Profits kept rising, and the dividends rose alongside those earnings.

Once you had your hands on this ownership stake, you didn’t have to do anymore work beyond examining the annual report each year to determine if the business was still one you wanted to own; that you still believed had excellent economics; that you still thought would be earning more money in the future, while earning a fair return on capital in the present. You were free to go about your life without giving much thought to the firm as there were talented full-time managers running the place.

During those 30 years, you would have almost never seen this chart anywhere on television, in newspapers, discussed on the radio, or printed outside of the company’s own financial reports. The news focuses on what is happening at the moment – it almost never looks out and asks the question, “How does this matter to a long-term owner?”.

Even today, look up analyst coverage and news stories on the enterprise. Everyone’s talking about the next quarter, or year. Yet, everyone acknowledges that for the next generation the firm is probably a fantastic holding. Investment portfolios aren’t managed that way, anymore. People just want to know whether shares will be up or down relative to the S&P 500 this time next year. I don’t have a clue whether Nestlé will beat the index in the coming four quarters, but, again, I am willing to play what I see as highly favorable probabilities that it should make me a very nice return in the coming quarter-of-a-century.

I want more Nestlé. I will have more Nestlé. My current analysis may indicate a hypothesis that it could compound at only 7% to 12% long-term, but few things in life are that stable in terms of the internal profits and losses (again, the stock market won’t be that calm – the price of Nestlé shares is likely to fluctuate wildly, just like all other equities and there are always risk with any stockholding – while presently unthinkable, a company like Nestlé can go bankrupt, causing meaningful losses. That’s the nature of the world and the price an investor must pay for the potential returns generated by equities.). I have enough, other, high returning cash generators that I can indulge my desire to plant a few oak trees that, while they may grow more slowly, might very well pay off in a major way during my own retirement as well as when my future children and grandchildren inherit at least part of the estate.

I have to fund the pensions in a few months, as well as make some tax payments for the companies, but I think I’ll be able to keep constantly nibbling at the stock, picking up shares here and there as cash is generated by the other assets. I should be buying, not talking; writing checks, not posts on my blog.