A Quick Cash Flow Statement Lesson – A Look at How McDonald’s Real Payout Ratio Is 110%, Not 54% As First Appears

McDonald’s is one of those businesses that I love. The last time we talked about it was when I wrote the 25 Year Investment Case Study of McDonald’s, and showed how you could have turned $100,000 into anywhere between $1,839,033 and $5,547,089 depending on how you handled dividend reinvestment and the Chipotle split-off back in 2006, and the sorely lacking media coverage of McDonald’s results in February. No matter which way you look at it, despite periods of overvaluation and undervaluation, alternating with the underlying performance and the emotional moods of shareholders, McDonald’s has been a fantastic company. It makes its employees and shareholders a lot of money. It gives society something it wants, whether that be a plain salad with side of fresh fruit and a non-sweetened iced tea or a double cheeseburger with french fries and a Coca-Cola.

What makes McDonald’s unique is that it is a cash machine in harvest mode. It is one of the few businesses that are effectively returning more than 100% of the after-tax profits to the owners every year, even though it appears as if the payout ratio is 54%. That’s certainly the figure you see whenever you run a stock screen or calculate the total dividend distributions relative to net income. What it misses, however, is the Board of Director’s understanding that growth in the McDonald’s system will come from increases in food prices (providing a very nice inflation hedge), expansion into other categories (such as the direct assault on Starbucks with the introduction of cappuccinos and coffees several years ago), and, in rare cases, the acquisition and development of up-and-coming restaurant concepts (such as the Chipotle brand, which is now a stand-alone business, traded as its own stock). The only rational thing to do with the billions of dollars in surplus profit generated every twelve months is to give it back to the people who own the company. If you are a stockholder, that means you.

To see how this works, we need to look at the cash flow statement and then compare it to something in the 10K filing.

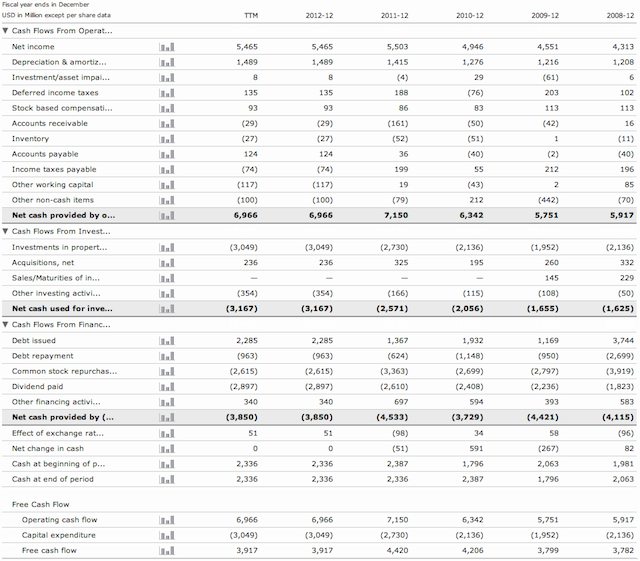

First, let’s take a look at the cash flow statement for the last five full fiscal years. We’ll ignore the trailing twelve months for now because the 1st quarter results aren’t yet finished so they are identical to the 2012 numbers.

Over the past five full years, McDonald’s has generated after-tax profits of $24.778 billion. During that same period, it sent $11.974 billion of that profit out to the owners in the form of cash dividends. If you hold your shares directly, your dividends were either reinvested for you or, alternatively, you received the cash through a direct deposit to your financial institution or a physical check in the mail. If you hold your shares in a brokerage account, you would have seen deposits from the McDonald’s Corporation appear within the brokerage account holding the stock.

What is interesting is that over that same period, McDonald’s spent $15.393 billion buying back its own stock. It has returning more money to the owners this way than it has through cash dividends. Before we can decide if the strategy has been successful, we need to see the actual reduction in shares, stripping out accounting considerations and rules. To get started, I’ll look at the 10K filing for the start of the period. I see this line on the cover page:

![]()

When I pull the most recent 10K, I see this line on the cover page:

![]()

That means that, temporarily ignoring the potential dilutive effects of stock options, we can see at first glance that McDonald’s had a net reduction of 148,851,621 shares outstanding. If it had not bought back stock, the $5.465 billion in profit last year would have needed to be split among 1,151,643,390 shares, not the lower 1,002,791,769 shares (it’s a bit more complicated because GAAP rules call for using the weighted average shares outstanding, but it’s not important now, I’m trying to explain the underlying economic concept).

That means profits per share for 2012 would have been $4.75, not the adjusted $5.45 that our analysis indicates is the owner’s cut (again, temporarily stripping out the weighted average share outstanding accounting rule and potential dilution, which in the case of McDonald’s, is minor). That means your profits are 70¢ higher for every share. As of today, McDonald’s trades at 18.6 times earnings, so those 70¢ are responsible for $13.02 of the $99.69 in current stock price. If, instead, McDonald’s had paid out that $15.393 billion, you would have received $13.37 in additional cash dividends. It’s nearly identical. Factor in tax efficiencies, and you are exactly as rich as you would have been had the repurchases been distributed as cash dividends, instead.

The more astute among you are probably wondering how McDonald’s spent a combined $27.367 billion on share repurchases and dividends, when net profits were only $24.778 billion. The answer: Profits may have been $24.778 billion over those five years, but the actual cash generated from operating activities was $32.126 billion due to various accounting adjustments. On top of this, the company issued additional net debt of $4.113 billion to take advantage of low interest rates, providing a source of funds, and raised $2.6 billion from other financing activities.

Long story short, management was playing with around $38.839 billion over those five years, not $24.778 billion. It returned $2.589 billion more to owners than the net earnings figure! The real payout ratio is more than 110% of profits, not the 54% that appears at first glance. Then, on top of this, it funded its capital expenditure needs of net $5.399 billion ($12.003 billion gross capital expenditures – $6.604 billion in depreciation charges; there would be some tax adjustments, but again, I’m trying to teach you the simplified, big idea concepts so you understand what is going on with the financial statements.)

The thing you should be picking up on right now is that McDonald’s real profits – the cash that could be taken out of the business if you owned it entirely without hurting the competitive position – are higher than the reported profits.

Normally a company with a payout ratio higher than 50% can be somewhat problematic for a long-term owner. In this case, that really isn’t applicable because McDonald’s entire financial structure is based upon franchisees providing the expansion capital, plus the food itself has a significant inflation hedge built into it due to the nature of the product, making it an exception to the rule. In addition, we didn’t even get into the interesting fact that if the United States continues to run massive budgetary deficits, McDonald’s profits could soar because it generates a vast majority of its sales and profits in currencies other than the U.S. dollar.

McDonald’s Is Not Cheap Right Now, But To a Long-Term Owner, That May Not Matter

It’s abundantly clear that McDonald’s shares are not cheap right now. They’d probably be a fair shake at around 15x reported earnings, which would provide you with a starting earnings yield of 6.67% or so. With respectable, but relatively modest, growth in profits per share, in a decade, you’d be looking at a 13.12% or greater earnings yield on cost. On top of that, you’d have received cash dividends for ten years, which could have been used to buy more shares of the businesses, accelerating that return, or even redeployed to make investments in completely non-related companies (for example, I recently used a McDonald’s dividend, pooled it with dividends from Microsoft, General Electric, and several other businesses, and used the cash to buy more shares of Wells Fargo & Company. It all comes down to your particular ownership strategy.)

McDonald’s is one of those companies for which I love to write a check whenever it is cheap or even decently priced.

If I were following a dollar cost averaging plan, though, and having cash taken out of my checking account regularly to buy shares of McDonald’s, then reinvesting those dividends through a DRIP account, I wouldn’t worry about the slight overvaluation. In 25 years, it shouldn’t matter. It should be a rounding error. I can’t guarantee that – the company could go broke and cause significant, permanent, and painful losses – but I think the odds are better than average.

On that note, McDonald’s is so shareholder friendly that they are one of the few companies that has a big red button directly on its website to become an owner! You click it, agree to have at least $50 per month taken out of a checking or savings account, and they will charge you very low fee of only $1 to $2 per transaction to buy the shares for you and stick them in an account registered to your name. They’ll even let you establish accounts for your children and grandchildren. As a percentage of principal, it would probably be advisable to at least put aside $250 per month so the fee represented less than 60 basis points but that’s just me.

Personally, I love owning McDonald’s. It’s on my list of companies that I am willing to write a check to acquire, augmenting my ownership position whenever the price is right. The restaurant shares sit on my balance sheet, producing cash. I love getting those direct deposits. I’m telling you, it’s no different than a video game or board game. Your job is to put together a collection of assets that throws off the most money, while providing sustainable long-term growth and safety of principal. That strategy results in “winning” life in a lot of ways, in the sense that it can exempt you from many of the problems that are a struggle for most people. You don’t have to worry about losing your home, or putting food on the table; you don’t have to worry about working for someone you don’t like or missing your kid’s school pays; you don’t have to think about medical bills or lose sleep over a downturn in the economy.

On a side note, it’s funny how life influences events. I wouldn’t have been thinking about McDonald’s, nor would this article have ever been posted, if Aaron hadn’t decided that was what he wanted for lunch and dropped off a chicken sandwich and iced tea for me at my desk. Needing a break from work, I started writing as I enjoyed it …

Update: Several years ago, I placed this post, along with thousands of others, in the private archives. The site had grown beyond the family and friends for whom it was originally intended into a thriving, niche community of like-minded people who were interested in a wide range of topics, including investing and mental models. I decided, after multiple requests, to release selected posts from those private archives if they had some sort of educational, academic, and/or entertainment value. This special project, which you can follow from this page, has been interesting as I revisited my thought processes about a specific company or industry, sometimes decades later. In this case, I release this post on 05/25/2019. I felt it provided some insight into how the reported earnings figures might be higher or lower than what a reasonable business person might consider the “true”, or “intrinsic”, earnings.

One major change that has occurred in the six years since this post was originally published: Aaron and I relocated to Newport Beach, California in order to have children through gestational surrogacy. Within a window of a couple of years around that relocation, we also sold our operating businesses and launched a fiduciary global asset management firm called Kennon-Green & Co.®, through which we manage money for other wealthy individuals and families. That means we are now financial advisors (or, rather asset managers operating under a investment advisory model as we are the ones making the capital allocation decisions rather than outsourcing those to fund managers or third-parties), which was not the case at the time this was written. Accordingly, let me reiterate something that should be perfectly clear: this post was not intended to be, and should not be construed as, investment advice. Also, for the sake of full disclosure, I’ll state outright that Aaron and I, as well as some of the clients of our firm, own shares of McDonald’s. We express no opinion as to whether or not you should buy it. Any company can do poorly or even go bankrupt. There is no guarantee that McDonald’s will generate a profit or make money for shareholders. We may buy or sell McDonald’s stock for ourselves or our clients in the future and have no obligation to update this post or any other historical writing. You should talk to your own qualified, professional advisors about what is right for your unique circumstances, goals, objectives, and risk tolerance.