Let’s Talk About Investing in Oil Stocks

I’ve received a significant number of requests over the past few months asking that I discuss what is happening with oil, natural gas, pipeline, and refining companies; to explain how I look at the situation and the sorts of things Aaron and I discuss when we’re allocating our own capital or the capital of those who have entrusted their assets to us.

It’s a big topic with a lot of niche considerations but I want to take some time today to address the oil majors; the handful of mega-capitalization behemoths such as ExxonMobil, Chevron, Royal Dutch Shell, Total, ConocoPhillips / Phillips 66, and BP, with resources that rival entire governments and have a diversified operating structure, typically consisting of some combination of 1.) exploration and extraction, 2.) refining, 3.) chemicals, and 4.) distribution or retail sales rather than specializing in any one thing, allowing each to benefit from economies of scale and lower overall operating costs. This diversified business model arose in no small part due to the experience of John D. Rockefeller and his fellow oil tycoons around the world back in the 19th century when they witnessed firsthand how poor planning could turn an otherwise lucrative partnership or corporation into a money-losing, life-destroying nightmare. In 1866, by way of illustration, the price of a barrel of crude oil fluctuated in non-inflation adjusted terms from $0.10 to $10.00; an oscillation that is all but unthinkable today, making the recent movement in the commodity look cute in comparison.

By making sure they built empires that could survive all environments, and provide comfortably secure dividends for owners through “the cycle”, as it is sometimes called, they created these rare powerhouses that are among the biggest, oldest, and most widely held of the blue chips. They represent a good chunk of the underlying holdings of certain index funds, such as the S&P 500, and have a cherished place in the portfolio of nearly every pension, widow, and conservatively managed trust fund in the United States. They’re also an enduring favorite of many of the secret millionaires we so frequently discuss. When former Mobil secretary Phyllis Stone died, a local charity was shocked to discover her donation following the revealing of a $6,000,000 fortune she had built up consisting mostly of tens of thousands of ExxonMobil shares, acquired over the decades from her modest income. Perry “Bit” Whatley, a retired machinist, amassed nearly $2,000,000 due, in part, to his ExxonMobil stake, which ultimately led to a protracted legal fight after a family drama involving attempts to seize the portfolio. A barber named Earl Doren never made it through eighth grade but following a career in the United States military, he went into business for himself, working for more than forty years. Some of his clients were smart businessmen, to whom he listened. He ended up with a $1,800,000 fortune that he gifted to a charitable trust, which included a sizable ExxonMobil position. On and on the roster goes, all the way up to old money and royalty; the Queen of the Netherlands is a major shareholder in Royal Dutch Shell, making her family billionaires, as is Queen Elizabeth of England.

If you’re reading this and you have any investments, anywhere, the odds are good somehow, some of that money is being generated from one or more of the oil majors. You are big oil and your family is an oil family. It is the backbone of the global economy; the producers of hydrocarbons that make possible the manufacturing, production, and distribution of everything from paint to carpet, chemicals to electricity. Without it, modern civilization could not exist.

Oil Companies, and Thus Oil Stocks, Have Unique Characteristics That Make Their Business Model Different from Most Operating Companies

If you own a business, whether it be a retail store, a doughnut shop, a medical supply company, or a manufacturing plant, you are typically looking to increase sales and profits with each passing year; to examine this twelve-month period in the light of the former twelve-month period to see if things are improving. As seemingly arbitrary as it is, we use one trip around the nearest star as the line of demarcation for every period of measurement even though it doesn’t have any particular relevance to the actual cycles of most firms. When you go to sell shares of your business either to cash out or to get an infusion of capital to increase the speed at which you can grow the enterprise, investors will examine the recent results, determine what they think the future results will be based upon the financial statements and other variables, then offer you a multiple. “I see here, Mr. & Mrs. Smith, that your chocolate business generates $3,000,000 in after-tax profits every trip around that star, and has historically grown at 6% per annum. We’ll offer you $40,000,000 to acquire it.”

The oil majors aren’t like this. They have extraordinarily long cycles of identifying, sourcing, extracting, refining, producing, distributing, and selling their products and services, sometimes stretching for 30 to 50 years or longer. Their executives, operators, and shareholders cannot think in terms of quarters, but rather, they must look at the income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement through the lens of decades or generations. Part of this is logistical – you don’t wake up one morning and decide you need to find huge oil reserves, having them fall into your lap; you have to search, plan, and pay for them far in advance – part of it is a by-product of the fact that demand for the oil majors’ primary products, ranging from crude oil, jet fuel, gasoline, heating oil, motor oil, and more, ebbs and flows with the larger business cycle of economic expansion and contraction. You can have multi-year periods when you’re on the receiving end of torrents of earnings that drown you and your fellow owners in record-shattering profits only to be followed by the spigot getting shut off, mass layoffs, and forced curtailing of planned projects to save on the capital expenditures as you want to reserve as much cash as you can.

The oil majors are not just oil companies. They are so much more. Most are integrated with refining businesses that then turn the raw materials into higher-margin substances, such as jet fuel or engine oil. They own huge chemical companies (ExxonMobil, by way of example, would be one of the largest stand-alone chemical businesses in the world if it were forced to divest its subsidiary). They own transportation businesses. They own franchise operations (gas stations and convenience stores).

In practical terms, for existing and potential owners, it means you’re missing the big picture if you try and look at the current price-to-earnings ratio, earnings yield, price-to-sales ratio, or many of the other popular metrics in any given year. It’s entirely possible for your oil major stock to be significantly overvalued at 10x earnings and significantly undervalued at 20x earnings based on where we are in the cycle (the former is known as a “peak earnings value trap“).

Take, for example, the old Standard Oil of California, or as most people know it these days, Chevron. It has fallen from a high of $129.53 in the past 52 weeks to $71.45 as of this moment. Yet, if you knew for certain that the price of crude was going to stay below $40.00 per barrel for the next five or ten years, you could objectively state that it is significantly overpriced. In fact, if you knew for certain that the price of crude was going to stay below $40.00 per barrel for the next five or ten years, you could objectively state that the entire oil sector in the S&P 500 is the most overvalued sector in the index by a wide margin.1

For the oil majors (as opposed to the pure plays, which are a different story), that’s not the whole picture. It is entirely possible for a trader or hedge fund manager to say oil stocks are overpriced at the moment, calling for them to decline and a long-term investor to say that oil stocks are undervalued at the moment, preaching you should use your funds to load up on them. That seems almost nonsensical; a paradox. Nevertheless, it’s true when you understand one fundamental fact: When you buy a share of the oil majors outright, paying for it in cash and locking it away, you are being paid to absorb volatility over multi-year periods.

Read that last paragraph, again. Think about it for a few minutes. Let it sink in so it becomes a permanent part of your investment file.

Got it? Now, let’s examine how it works.

Long-Term Investors in the Oil Majors Are Being Paid to Absorb Volatility Over Multi-Year Periods

In recent weeks, there have been several discussions in the comments about the highly-respected work of Dr. Jeremy Siegel at the Wharton School of Business. It seems only appropriate he would come up in the conversation today because a decade ago, he released one of my favorite books, which over nearly 300 pages provided an examination of the original S&P 500 components from February 28th, 1957 through December 31st, 2003; as if a buy-and-hold investor came in, acquired all of the stocks, and then sat on his or her behind. Dr. Siegel and his research assistants performed exhaustive calculations, tracing the compound annual growth rate of every component through mergers, spin-offs, split-offs, bankruptcies, buyouts, and more. For those of you who haven’t read it, the appendices alone are worth the price. Pick up a copy the first chance you get and read it cover-to-cover. It’s called The Future for Investors: Why the Tried and the True Triumph Over the Bold and the New.

Toward the end, he discusses the dominance of oil. In the original S&P 500 index of 1957, 9 out of the largest 20 firms were oil companies. Relatively, the oil sector has shrunk significantly in the meantime. Yet, for the almost half-century his study encompassed, he found that when he traced the results of those top twenty largest firms, the highest performing five businesses at the end of the period all came from the oil sector. In fact, 7 of the top 10 highest performing among the former largest component weightings came from the oil sector. The oil majors, as a group, outperformed the S&P 500 as a whole by 2% to 3% per annum for nearly half a century. (Don’t scoff at that. To put it into perspective, if you could earn an extra 3% over 50 years, you’d end up with triple the terminal net worth. It’s life changing.)

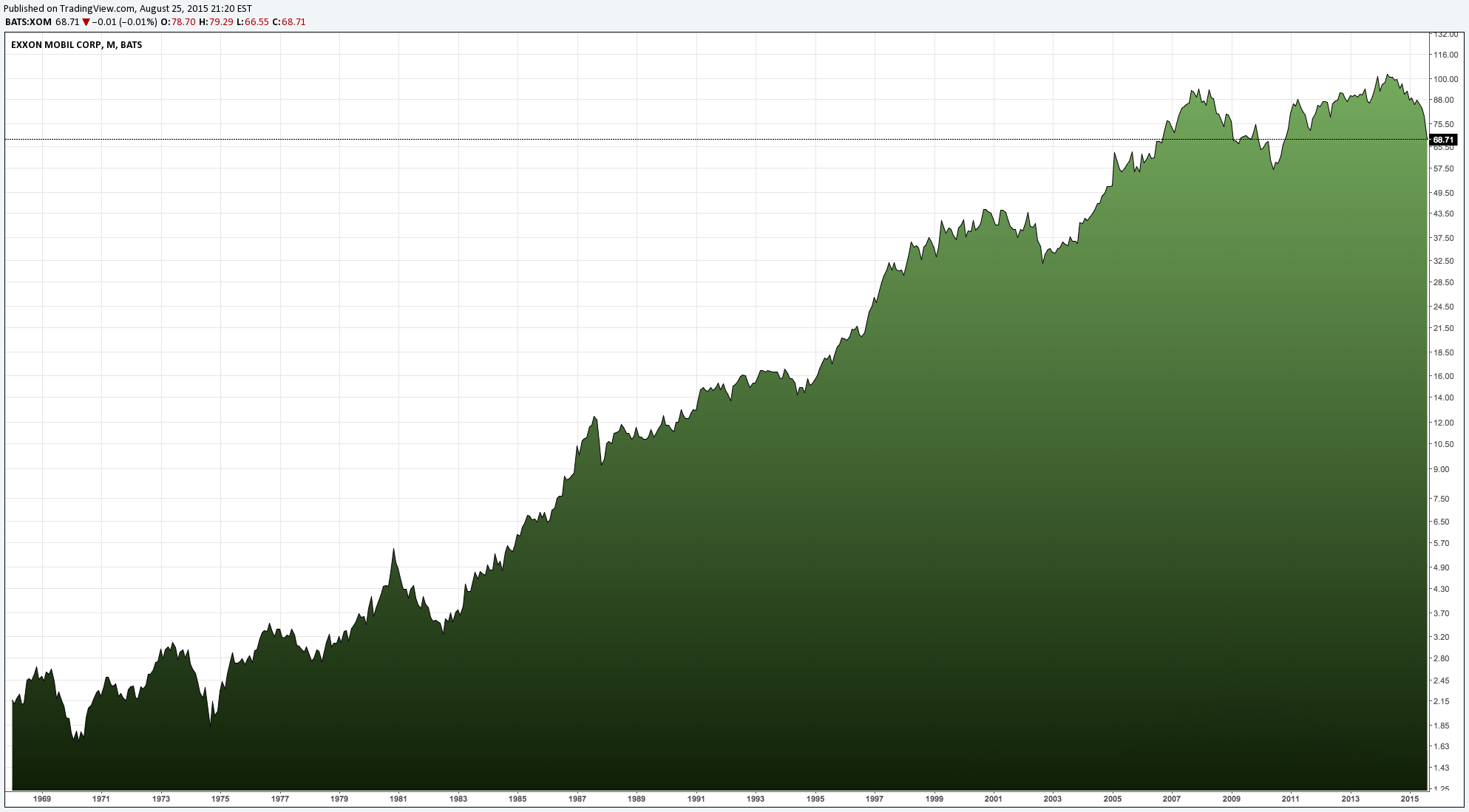

How could this happen? Oil shares are notorious for these boom-and-bust cycles; for skyrocketing then collapsing or going sideways for 5, 7, 10 years at a time. Indeed, when I did my 25-year case study of Chevron, I noted how the stock never seemed to trade outside of a range of $40 per share to $120 per share if you picked up the newspaper and weren’t paying close attention. How can it be that an owner of these massive corporations ended up not only matching the S&P 500, but substantially exceeding it over the same period to the point the ending differential in wealth was staggering? Take a look at the logarithmically-adjusted chart for ExxonMobil (it treats a rise from $10 per share to $100 per share the same as a rise from $100 per share to $1,000 per share since it represents the same mathematical gain and helps avoid skew toward larger numbers). The chart covers all of the past data I can easily access from a publicly created tool you yourself can replicate so it encompasses a slightly different period (the late 1960’s-today) than Dr. Siegel’s research did but the results are comparable because the same powers are at work.

What do you notice? There are many times when you’d buy ExxonMobil and watch it fall 20%, 30%, 50%, then take 3-5 years just to get you back to breakeven on a share basis alone. It does not appear to be a recipe for getting rich, let alone trouncing the indices but, somehow, someway, there’s a more than 30-fold rise in stock price. That doesn’t even include dividends or reinvested dividends, which are often a major part of the total return of big oil. What strange magic is at work? How could such a thing occur when you spend most of your time sitting on big losses or going sideways?

The answer can be found in the difference between long-term investors who buy through the cycle, absorbing the volatility, and short-term traders who make money flipping the stock for short gains. Shorter-term investors (5 years or less) tend to buy or sell the stock based on what they think earnings are going to be or whether the stock will rise or fall. Longer-term owners look at the premier energy company on planet Earth and conclude that, when the shares are attractive, as long as they hold for several decades (and sometimes accept paper losses that last longer than entire Presidential administrations), the odds are good they will eventually emerge wealthier due to a combination of:

- The mathematics of increasing dividends reinvested at a time of declining stock prices. As the stock price falls, your dividends buy more shares. As the company raises the dividends, your dividends buy more shares. Working together, you get this effect that starts to make a huge difference once you get 15, 20, 25+ years out in the future.

- Share repurchases authorized by stockholders and overseen by the board of directors that increase the absolute equity ownership per share as outstanding share count declines

- The ability of the oil majors to use market wipe-outs to buy up their competitors’ assets for pennies on the dollar after the weaker competitors have to beg for mercy in bankruptcy court or who have to acquiesce given their inability to remain independent when cash is tight, unable to fight off non-desired suitors; an ability that arises from the integrated, multi-stream earnings model

Let’s look at ExxonMobil to illustrate how these work. We’ll start with the first two – reinvested dividends and share repurchases – then move on to the last point in a moment.

How the Major Oil Stocks Accelerate Returns with Reinvested Dividends and Share Repurchases

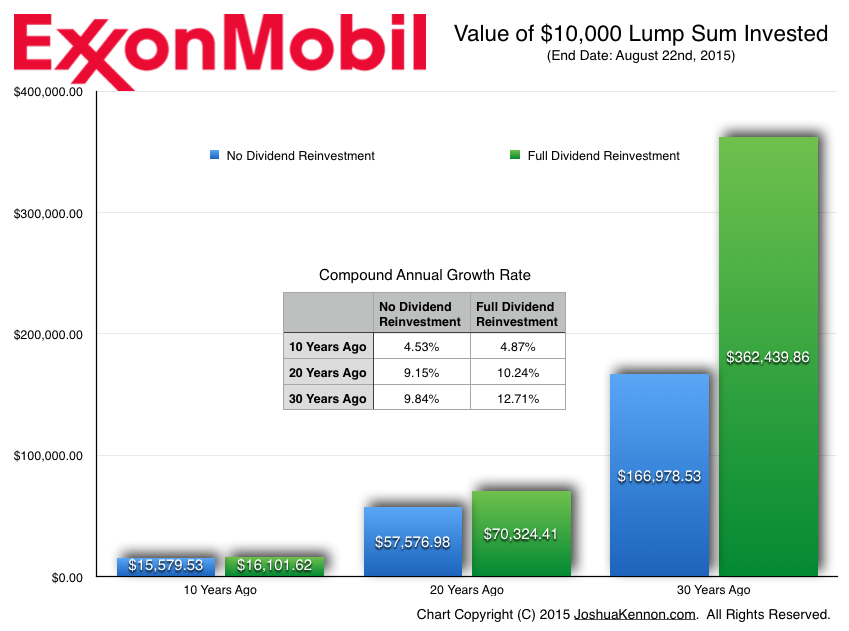

Keep in mind that since we are in the middle of an oil crash, the figures are far less attractive in terms of terminal value than they were last year, when they would have been nearly 50% higher due to the share price reaching almost $105. It’s the nature of the oil majors.

Note: The “No Dividend Reinvestment” figure shown in the chart is for total return (share appreciation/depreciation + dividends). Figures do not reflect taxes or inflation.

Even with the huge drop in ExxonMobil’s shares as we begin another crude oil crash – this one the worst since the legendary collapse of 1986, which took everyone from wildcatters to bankers by surprise and devastated the lives of millions of people – the full dividend reinvestment portfolio of ExxonMobil over the past 30 years has compounded at 12.71% compared to 10.61% for the S&P 500. That 2.10% differential might not sound like much but there’s a big difference between a $362,439.86 ending figure and the S&P’s $195,978.90 ending figure. It’s $166,460.96, or 84.94% more money. (Again, the number was much more impressive last year, underscoring the nature of the industry.) Generally speaking, you should not buy ExxonMobil unless you plan on making it a generational holding; one that is passed down through the family tree for you, your children, and your grandchildren to enjoy the stream of ever-increasing dividends while management figures out how to increase profits from all divisions.

The same pattern plays out over and over again. When Dr. Siegel looked at at the 1957-2003 original component S&P 500 returns, he found that:

- Royal Dutch Petroleum (now Royal Dutch Shell) compounded at 13.64%

- Shell Oil (now Royal Dutch Shell) compounded at 13.14%

- Socony Mobil Oil > Mobil (1966) > Now ExxonMobil compounded at 13.13%

- Standard Oil of Indiana > Amoco (1985) > Now BP (1998) compounded at 12.83%

- Standard Oil of New Jersey > Exxon (1972) > ExxonMobil (1999) compounded at 12.55%

- Gulf Oil > Gulf – Chevron (1984) > ChevronTexaco (2001) > Chevron compounded at 12.14%

- Standard Oil of California > Chevron (1984) > ChevronTexaco > Chevron compounded at 11.62%

- Texas Co. > Texaco (1959) > ChevronTexaco (2001) > Chevron compounded at 10.93%

- Phillips Petroleum > ConocoPhillips (2002) compounded at 10.76%

The only relative failure among the initial bunch was Rockefeller’s old Marathon Oil, which wasn’t even publicly traded on its own for a long time but was, instead, a subsidiary of U.S. Steel, drug down by the performance of the low-profit, high-capital steel industry.

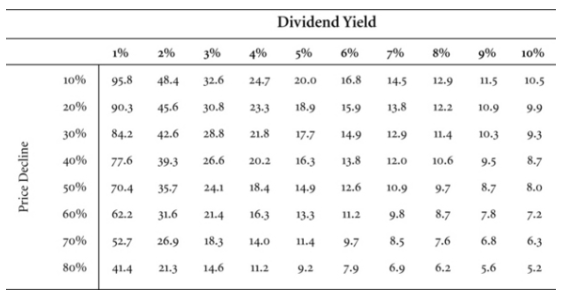

The secret is partially found in the higher-than-average dividend yields. Dr. Siegel produced two charts to explain the math to those who hadn’t run the numbers themselves (on pages 150 and 151 of the aforementioned book) demonstrating how reinvesting dividends in falling stocks of fundamentally good businesses could lead to lower breakeven points and outsized results down the line when the industry recovered; a perfect explanation for the boom-and-bust nature of big oil, refining, and chemicals. He calls this the “Return Accelerator” and explains, “Dividend-paying stocks do well through market cycles, since investors who reinvested dividends accumulate more shares during bear markets. Table 10.2 shows how many years it takes after a stock declines for investors to achieve the same return they would have received had the stock price not declined. These tables assumes the firm maintains its dividend. The investor recoups the price loss because the lower price allows dividend-reinvesting investors to accumulate more shares than they would have accumulated had the stock never declined. The value of these extra shares eventually surpasses the magnitude of the price decline, making the investors better off. As can be seen, the greater the dividend yield, the shorter the time needed for investors to recover their losses. Surprisingly, the table also shows that the greater the decline in price, the shorter the period of time needed to break even, since reinvested dividends accumulate at an even faster rate.”

TABLE 10.2: YEARS TO BREAK EVEN AFTER PRICE DECLINES

Source: Jeremy Siegel Table 10.2, Page 150, The Future for Investors: Why the Tried and the True Triumph Over the Bold and the New

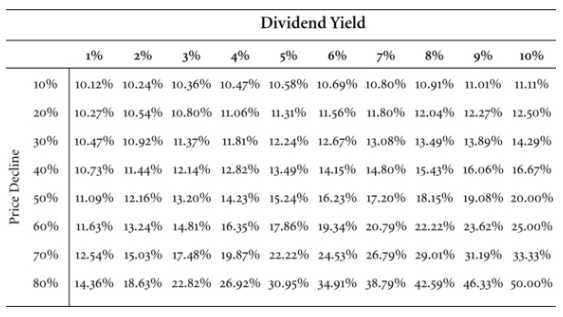

He continues later, saying, “Table 10.3 illustrates the return accelerator. It shows the return investors would earn if the price of the stock returns to its original level after the number of years indicated in Table 10.2. We noted above that if a stock had a 5 percent dividend yield and declined by 50 percent, it would achieve the same return in 14.9 years as a stock that had not declined at all. If after 14.9 years, the stock that fell 50 percent recovers to its original price, the annual return on the stock over those 14.9 years would rise to 15.24 percent, a return that is 50 percent greater than what the stock would have been had the stock not fallen in price.”

TABLE 10.3: ANNUAL RETURN WHEN PRICE RECOVERS

Source: Jeremy Siegel Table 10.3, Page 151, The Future for Investors: Why the Tried and the True Triumph Over the Bold and the New

In other words: The more painful the busts, the longer they last, the higher the eventual compounding return. You’re being paid to absorb volatility.

Firms that intelligently repurchase shares achieve the same effect as Siegel goes on to explain in the subsequent passages on buy backs. For ExxonMobil, this is a major part of the strategy, though there have been some less-than-ideal allocation practices in the past with most repurchases coming during boom periods to the dismay of certain financial journalists and analysts. Exxon was steeped in the Rockefeller culture and conservatism (up through the 1980s, the legendary old-time religion of the patriarch remained in the board room, which opened meetings with a prayer). It prioritizes the safety of the dividend over the amount of the dividend, having lower payout rates than its European counterparts. Instead, when times are good, it takes the earnings and repurchases unfathomable amounts of stock, destroying it to reduce the outstanding tally. Pull a recent ValueLine report on the firm and you’ll see that in 1999, there were 6.954 billion shares outstanding. This year, the oil giant is expected to have reduced that to 4.17 billion shares outstanding. That’s 2.784 billion shares gone. Each share bought in 1999 now represents 40% more ownership of the actual business. Spreading dividend distributions over fewer shares is one of the reasons it has been able to hike the dividend rate per share from $0.84 back in 1999 to $2.92 per share today. (The year I was born, the dividend was a split-adjusted $0.376 per share. Had you never reinvested any of your dividends, nor bought another share, you’d have watched your per share income rise 7.77 fold.)

Take it all together and the picture starts to emerge, fully alive and brilliant. You see how, especially in tax-sheltered accounts, it might be viewed by wealthy and experienced investors as a wise decision to buy firms like Royal Dutch Shell or ExxonMobil at the time the stock is collapsing, plowing the dividends back in on themselves, accumulating year after year despite seeing tons of red ink on your account statements. You start to understand how 40% unrealized losses brought on by an oil crash don’t mean much in the face of 4%, 5%, 6%, 10%+ (in the case of the 1930s and 1980s) cash dividend yields as you amass more shares with the rich payouts.

How the Major Oil Companies Strengthen Their Competitive Positions and Future Cash Flows During Oil and/or Stock Market Collapses

Meanwhile, the oil majors lay the groundwork for significant profitability increases down the road during crashes. The economies of scale they possess due to their enormous balance sheets and technical expertise allow them to drill or extract oil and natural gas at a fraction of the price their smaller competitors can under most circumstances. That means they can remain profitable for longer as the price of energy collapses. Their less profitable counterparts get into trouble, especially if they are in debt. Many go bankrupt and/or find themselves severely distressed, allowing the giants to come in and buy up their assets, debt, and in some cases, equity, for a mere fraction of what it would have commanded prior to the decline. They sail through the nightmare relatively unharmed (take a look at what has been happening at ExxonMobil and Royal Dutch Shell over the past year – with refining margins so high, it’s been softening the blow from the oil free fall).

Indeed, during the last major collapse caused by the Great Recession of 2008-2009, ExxonMobil geared up and acquired XTO Energy in 2010, paying $36 billion for the deal to close (it issued 416 million shares of stock and took on $11 billion in debt but, in exchange, became the largest natural gas producer in the United States). ExxonMobil then used the XTO subsidiary as a vehicle to acquire additional natural gas companies and acreage, tripling its size; e.g., see the 17,800 bought from LINN Energy almost a year ago. All of the newly issued shares have been repurchased and cancelled, undoing the dilution owners experienced, effectively converting it to a nearly all-cash deal (minus a necessary adjustment for the market price differential that occurred as the stock fluctuated in the interim, whereas it would have been a fixed amount in cash) but giving the old XTO owners the ability to defer capital gains taxes. Royal Dutch Shell announced recently it was acquiring BG Group for a whopping $70 billion, which will make it the world’s largest supplier of liquefied natural gas.

Twenty or thirty years from now, the price of these commodities will in all likelihood be considerably higher in nominal terms, the acquisition costs long paid in full. The stockholders of big oil will be collecting much larger dividend checks per share than they are now, perhaps not realizing that the nexus of those funds date back to this period. Those who watched their Royal Dutch Shell Class B shares go from $84.98 to $49.72 will have probably done extraordinarily well, their higher returns compensation for the volatility absorption they were willing to tolerate. And it will be deserved. A not-insignificant percentage of investors simply cannot function or remain calm when they see a huge, negative 41.5% next to their individual stockholding (one of the major benefits, and drawbacks, of index fund investing is it hides the underlying components from the inexperienced investor; he or she may have no idea that they’ve experienced identically proportionate losses to what they would have in a directly held portfolio of individual securities, allowing them to sleep better as night as bizarre as it sounds).

Strategies to Invest in the Stock of the Oil Majors

If you want to become an owner of the oil majors, here is what you might want to consider doing.

First, decide the valuation methodology you will use to acquire shares:

- Buy significant blocks when the businesses are being sold at prices that are objectively cheap on an absolute level compared to some sort of fundamental figure or figures such as ratios-to-book value, ratios-to-proven reserves, or sustainable-dividend yields (the stock simply falling [x]% is insufficient). For example, a handful of times, ExxonMobil has yielded more than 8% to 10%. When and if that day arrives, again, pay close attention. It is a few-times-in-a-century outlier. or

- Regularly dollar cost average into shares regardless of stock market or oil industry conditions, trusting that over 25+ years, it will work out for you. ExxonMobil, since we used it several times in this discussion, has the single best direct stock purchase plan I’ve ever seen. Almost everything is free; they pay practically all of your expenses and will allow you to have as little as $50 a month withdrawn from a checking or savings account to buy more stock. They want long-term, multi-decade, multi-generational owners.

Second, decide how you will construct the portion of your portfolio that resides in oil stocks:

- Buy one, specific firm or

- Create a basket that represents your own personal oil conglomerate, stuffing it with ExxonMobil, BP, Royal Dutch Shell, Chevron, Total, ConocoPhillips, Phillips 66, and a few other holdings, treating the basket itself as if it were one stock so an event like the BP oil spill doesn’t have too large of an effect on the overall portion (e.g., when BP blew out, oil prices went through the roof, increasing profits at competitors). You can weight them equally or you can create some sort of ratio that favors your preferred core holdings; e.g., 20% ExxonMobil, 20% Royal Dutch Shell, 10% Chevron, 10% BP, 10% Total, 10% ConocoPhillips, 10% Phillips 66%, 2.5% to four other firms.

Third, decide how you will treat subsequent allocations. Will you:

- Rebalance each of the holdings in accordance with their original weight once a year?

- Reinvest dividends into the firm that paid them or pool them at the bottom of the portfolio in cash then include those amounts in the annual rebalances and/or spread them evenly across all firms?

- Extract dividends to fund other investments a la the Rockefeller family trust funds, which for generations (up until recently in a fight over environmental causes) used their extensive energy investments to acquire a wide range of additional assets, including funding Apple and Gilead Sciences in the early days of those enterprises?

- Hold spin-offs?

- Sell spin-offs and reinvest in the parent company?

- What will you do if, as is prone to happen from time to time, one or more of your oil giants reduces or eliminates the dividend?

Next, stick with it for a quarter-century at least. Mentally make peace with the fact that you’re going to see jaw-dropping, horrific losses on paper from time to time and repeat to yourself, “I am being paid to absorb volatility others do not want on their balance sheet”. Make sure you won’t ever be forced to sell out early – don’t borrow on margin under any condition, don’t dip into your emergency cash reserves so you might have to liquidate at an inopportune time if disaster strikes. Then go on with the rest of your life.

You could very well buy a share of ExxonMobil (or whatever other oil giant you prefer, so insert name here) only to watch it sit at $0.60 on the dollar for the next seven years. That’s how this industry works. It’s during these times you accumulate more ownership as they go about gobbling up the world’s reserves from weakened competitors. (You’ll learn to take delight in the fact they reduce their own oil output when crude prices collapse but refining margins are high, buying other companies’ oil on the open market to feed into the refineries so they can keep their own reserves for the day when sky-high prices return.)

These aren’t empty words, it’s the way we handle our own capital. On Friday of last week, Aaron and I added some ExxonMobil to our portfolios through a couple of pension accounts that won’t begin payouts until 2042 at the earliest. Earlier this week, we substantially increased the stake to the point it is our fourth largest holding. There is a very real probability it falls to $50, $40 a share or less. If it does, we will dry our eyes with the 4.1%+ tax-free initial yield we managed to grab in the midst of the chaos; a yield that is all but certain to rise over time. Meanwhile, we take a more balanced, less concentrated approach for the accounts under our control; accounts that the people close to us will use to support themselves in old age with more equal amounts of ExxonMobil, Chevron, Royal Dutch Shell, BP, and Total shoved into their retirement and brokerage portfolios.

Some Final Thoughts on Investing in Shares of the Oil Majors

Are shares of the oil majors right for you? It depends on your timeframe and psychology profile. This is one of those areas where raw intelligence doesn’t seem to do much good. You’ll find drop-outs who went to work in the oil field but get the industry; understand its dynamics, when to buy, and how to hang on for dear life as if those equity certificates were the most precious thing in the world, enjoying a stream of checks for the rest of their time on this mortal plane and frequently amassing hundreds of thousands, or even millions of dollars in surplus wealth despite the volatility. On the other hand, you’ll have an otherwise brilliant person who falls apart at watching their $150,000 stake go to $60,000, hit the “sell” button, and swear off “playing the stock market”, as idiotic as that phrase is in this context, transferring the probable future payoffs to someone else with a stronger stomach and understanding of the economic cycle as it pertains to the real business model of the oil majors. (If you need to get a refresher course on how the world merely repeats itself – there is nothing new under the sun – go pull up past historical stories on crude collapses. The entire year 1986 New York Times archives is particularly useful as you could block out the date and almost exactly replay the current situation we are going through at the moment.)

One way you can alleviate this is to design the entire portfolio intelligently. There are certain industries, and companies, that do extraordinarily well when energy prices collapse; the oil majors’ pain is their gain. Consider that in the overall construction. Look to consumer staples like Coca-Cola and Hershey, which sail through booms and busts with equal aplomb. Hold some minimum level of liquid cash along with fixed income securities of short or medium-term duration to provide a buffer in the event of painful deflation. And above all, if you don’t understand what you are doing: Walk away. It’s easier for people who live near something like the Joliet refinery in Illinois to buy shares of ExxonMobil because they can see it. They watch the people walk into the plant every day. They see the products leave it. It’s real. They can reach out and put their hand against the fence or talk to the men and women drawing a paycheck. Never buy an ownership stake in something you do not fully understand or with which you are not fully comfortable.

As for the other areas of oil investment and speculation – the pure play exploration companies, the companies leasing equipment to producers, drilling rights, royalty unit trusts – it is not a place for beginners nor intermediate investors. It is totally unnecessary to becoming financially independent and you run a real risk of losing a substantial portion, if not all, of what you lay out to more experienced capital allocators who understand the industries. The only exception I think passes muster would be something like a directly-held, individually-built, equal-weight portfolio of some kind where diversification was in the hundreds (or more) of individual securities. It’s a very different thing to buy ExxonMobil or Chevron regularly, through boom and busts, than it is to buy Tidewater at $80.00 back at the high of 2007 only to watch it fall as low as $14.35 this year. It’s not a Hershey. It’s not a Clorox. It’s not a Colgate-Palmolive. It looks like a $10,000 investment with dividends reinvested over the past 30 years in that particular firm is now worth $16,417.81 for a pre-tax, pre-inflation compound annual growth rate of 1.67%. I’d have to check and see if there are any spin-offs or weird situations distorting the numbers but it’s a business on which one speculates, not makes long-term commitments. (In comparison, the same $10,000 lump sum invested in been-around-since-the-1800s Colgate-Palmolive 30 years ago with dividends reinvested is now worth $796,117.37, or 15.70% compounded annually. Give me dish soap and toothpaste any day. Johnson & Johnson? That comes to $639,929.85, or 14.86% compounded annually. Even General Electric, which makes the stuff for the oil and natural gas industry? That came to $231,169.85, or 11.03% compounded despite the worst meltdown since the Great Depression, which saw the legendary blue chip cut its dividend due to mismanagement of the banking operations.)

The last paragraph reminds me of a story that was relayed to me. Many, many years ago, I was visiting with a successful analyst at a white-shoe wealth management firm. This firm had a lot of extremely rich clients. All of the partners were rich, too. The analyst told me about a long-term client for whom they had accumulated a lot of riches; crushed the market over the decades their relationship endured despite occasional periods of underperformance due to the nature of their strategy, which involved seeking out deep value. During one particular era, when technology stocks were going through the roof, the investment committee of this firm looked over the client portfolio and for something like 2 or 3 years, didn’t have hardly a single buy or sell order executed, but rather kept him in highly appreciated positions of business like Johnson & Johnson, the deferred taxes effectively leveraging the compounding rate without much additional risk. One day, he called them agitated. “What the hell am I paying you for if you’re going to ignore me? For years I’ve watched all my friends buying these technology stocks and make a killing and you aren’t doing anything. You know how much money that 1.5% per year I pay you is on an account balance as large as mine?! I’m making you rich!”

The partner who took the call, and who had known this person for a long time if I remember correctly, said something along the lines of, “You’re paying us to make you money – and we have made you a lot of money over the years. Right now, we believe the best course of action is to do nothing; to keep you from your own worst instincts and stop you from making a mistake by selling these wonderful businesses we acquired at opportune times when they were being given away. Even more importantly, we want to keep you from then taking the cash you raise and plowing them into garbage that happens to be en vogue at the moment; companies with no real earnings, no real business models, and no hope of survival. You pay us for our advice. Our advice: Go play golf.”

That philosophy is perfectly suited to a position in the oil majors should you decide to become an owner. That can be hard. Go back up to the top of this post and enlarge the chart of ExxonMobil then think about whether or not you could sit there, owning the stock between 1969 and 1976 having made seemingly no progress were it not for the additional shares you held from the dividend reinvestment. Strap yourself in and be prepared for a wait that may last a significant part of the rest of your life. If that’s appealing to you, great. If not, nobody says you have to add more diversification by picking up a few of them. It is your money, after all. Do what makes you most comfortable within the bounds of prudence.

Footnotes

1 Complicating it further is you reach a point at which oil stocks fall so far they no longer trade as proportional ownership in a productive business based upon earnings alone. They either function as 1.) a mechanism for competitors to come in and buy the proven reserves (the commodity itself, with the business having no value), or 2.) a stock option or other derivative that exploits the operating leverage inherent in the business model and thus should be valued using some sort of Black Scholes approach; a speculation mechanism that can lead to speculator gains or losses. Both of those are far beyond the discussion we are having now and wildly inappropriate for nearly everyone reading this.

2 Some reinvestment calculations are from the Quandl data set and generated by a tool created by PK, a software engineer living in Silicon Valley. I haven’t verified the end figures by hand because it’s late and I need to move on to other things. They look roughly approximate enough, in my experience and in light of the past case studies I’ve done, to say they’re correct but I can’t personally vouch for the results. Be aware of that.