Get ready to add yet another secret millionaire to your case study files. Ronald Read passed away last June at 92 years old. The Brattleboro, Vermont man, who had no college education and drove a Toyota Yaris, always made a point of living below his means. He spent many years working as a gas station attendant and the rest of his career a janitor for his local J.C. Penney department store.

Read was a near perfect archetype of the academic research done by men like the late Dr. Thomas J. Stanley at the University of Georgia and Wharton professor, Dr. Jeremy J. Siegel. Like the super-majority of Americans who are in the top 1% of wealth, Ronald was stealthy about it, keeping his money a secret from even his own children and friends. They knew he enjoyed investing but were reportedly shocked to discover upon his death that he had a safe deposit box with a stack of stock certificates five inches thick.

This was in addition to the nearly dozen-and-a-half direct stock purchase plans in which he was enrolled via electronic registration to take advantage of the lower costs they offered now that stock certificates are expensive to order out in physical form. Read also had a modest brokerage account which contained a relatively small percentage of his portfolio.

The estate, with the help of Wells Fargo & Company, is adding up his holdings and trying to ascertain the extent of his fortune but at last count, they know he owned at least 95 businesses representing $8,000,000 in market value. Assuming a 3% dividend yield on the weighted assets, he was probably pulling down $20,000+ a month in dividend income before taxes on top of the roughly $12 an hour job he held.

His largest stock positions were:

- Wells Fargo & Company = $510,900

- Procter & Gamble = $364,008

- Colgate-Palmolive = $252,104

- American Express = $199,034

- J.M. Smucker = $189,722

- Johnson & Johnson = $183,881

- VF Corp. = $152,208

- McCormick = $145,055

- Raytheon = $142,970

- United Technologies = $140,880

How did Ronald Read get so rich?

Ronald Read, a janitor at J.C. Penney, left behind a portfolio of at least 95 companies with a market value of $8,000,000+. He would research stocks at the public library, acquire ownership stakes, and then sit on them for decade, even if some of them went bankrupt along the way, trusting compounding and diversification coupled with low (in some case, non-existent) costs would work its magic. He then left most of it to charity.

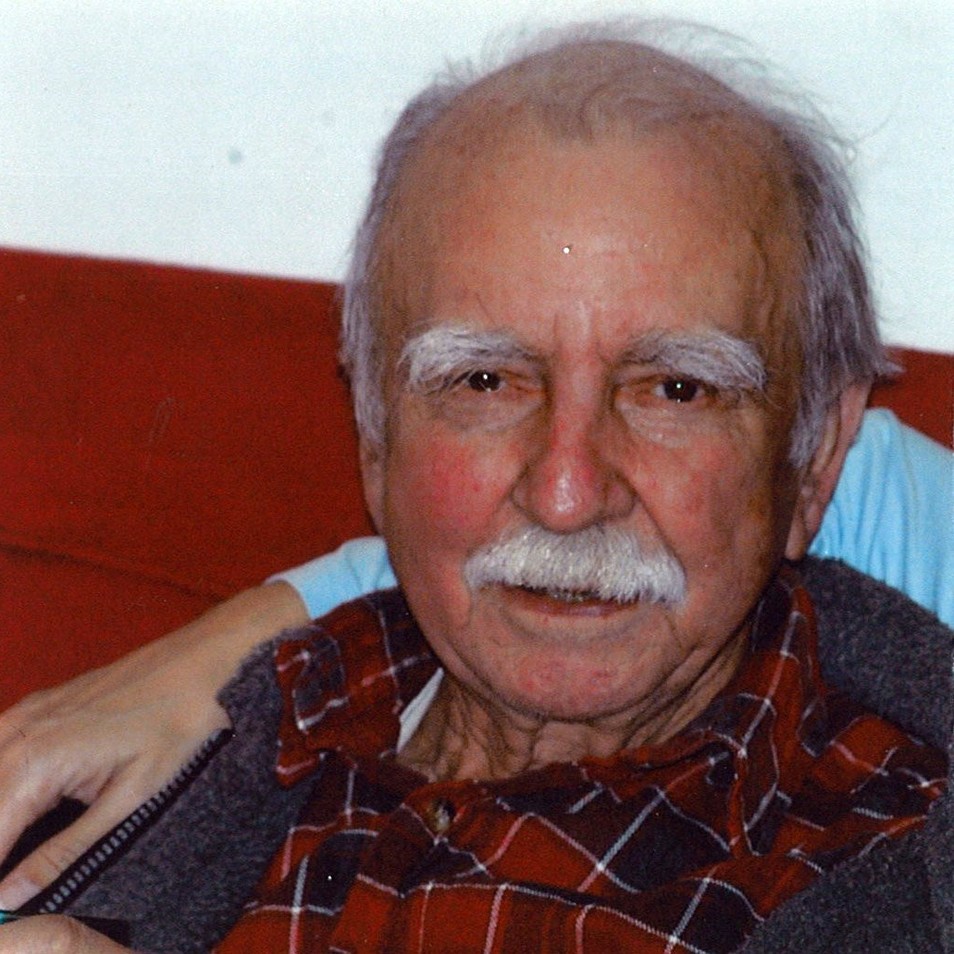

Image from Estate of Ronald Read

- He started small. According to The Wall Street Journal, the trades go back to the 1950’s and began modestly. They provide one illustration. On January 13th, 1959, when he would have been around 37 years old, he bought 39 shares of Pacific Gas & Electric for $2,380; a trade with an inflation-adjusted total of $19,200 or so in today’s purchasing power equivalent.

- He spent the last 60+/- years quietly, patiently, and regularly accumulating equity in some of the most successful businesses in the world, across a wide range of industries. He owned railroads, banks, credit card companies, industrial conglomerates, dish soap and toothpaste empires, packaged foods giants; you name it. Multiple times, he would have seen his portfolio value decline by 50% or more on paper but he just plugged away at it with discipline, acquiring more ownership of productive assets despite multiple wars, inflation, deflation, numerous changes in the tax code, the threat of nuclear annihilation; didn’t matter.

- He only bought ownership in businesses he knew and understood through first hand experience.

- He only bought ownership in businesses that paid him a dividend so he could physically see the check arrive in the mail, which he would then deposit and use to buy more shares, the goal being growing his stream of monthly passive income.

- He was like the super-rich Vanguard clients John Bogle discusses who buy individual stocks and never sell a damn thing. He largely eschewed turnover, with multi-decade holding periods. This guy was a true buy-and-hold investor. He understood the danger of activity, the advantage of deferred taxes, and the wealth-destroying nature of high fees.

- He grasped the math of diversification because he’d continue to hang onto his shares even if a business went into total bankruptcy; e.g., he held a stake in Lehman Brothers, which was wiped out in the Great Recession of 2008-2009. He relied on an intelligently constructed, diversified, representative list of common stocks that was arranged in such the inevitable losses were swamped by the growth and income of the other holdings.

I find the media’s response to Ronald Read’s death fascinating. Two examples:

First, in the original WSJ article, he is referred to as a “stock picker”, when he hardly resembled anything of the sort. He was a broad, buy-anything-of-permanent-value equity accumulator and stocks were merely a mechanism. Stock picker largely implies, and is almost exclusively used in the context of, people who buy shares of some hot business at one price to turn around and sell at a higher price. That was not Read’s method of operation. He wanted ownership, and to live off the money his assets pumped out regardless of subsequent stock performance.

Second, in a follow-up WSJ blog piece called Should You Invest Like Ronald Read?, he is called a simple-living Vermonter who enjoyed – and I quote – “playing the stock market”. Again, he wasn’t playing anything. This was not a guy sitting around staring at stock charts and trying to figure out an exit point. He appears, by all accounts, to have been totally agnostic to share price movement. He just wanted to grow his stream of income with each passing year, both through reinvestment and organic growth of the absolute dividend rates the firms themselves provided.

Perhaps I’m mistaken but I feel like that sort of loaded, misleading language gives the wrong impression to those who want to build a conservative, long-term portfolio.

Equally as interesting is that his life seems to make some people upset. Reading the comments around the Internet, you’d think that Read’s habit of not spending money by doing things such as wearing old clothes (why buy something knew if you can use a safety pin?) was a personal affront or failure of some kind. One person going by the name Thomas Nadeau wrote:

What a sad story of a life lived for a tomorrow that never came. This article makes his life sound laudable and virtuous when this should be a cautionary tale…

I think that is a gross oversimplification. Yes, I’ve warned you multiple times that your goal is not to die with the highest net worth possible, but rather to maximize the utility of your net worth to give you the life you want. Money is a tool. Nothing more. Nothing less. It has to be factored into trade-off decisions and measured against time, emotional costs, and all sorts of other variables that matter to you, personally. That said, by all accounts, it looked like Ronald Read was doing exactly what he wanted. He seemed to enjoy his life. He loved the process of investing. He liked watching his money grow. He didn’t need a lot of stuff to make him happy. He was living that advice. Those criticizing him without looking at the details which paint a picture as to his motivations are falling into a cognitive error. Believing that everyone wants and needs the same things you do to be happy is a mental model found under the theory of the mind group.

In fact, like many members of the top 1% or 2% of net worth who amass much larger-than-average estates, Read appears to have been motivated, in part, by altruism. He gifted nearly all of his money back to society, leaving legacies for a local hospital as well as the public library he regularly visited to research investments.