Economic Reality Isn’t Always Reflected on Your Account Statements

There is an account I handle as a favor for someone I know. This account has a very unique mandate. It holds a handful of stocks, has practically zero turnover, and once a new position is acquired, the dividends must be automatically reinvested into that business, cost-free, until disposition. The entire portfolio is held within a Roth IRA and this person is still more than 40 years away from retirement. Even if he or she never contributes another penny, the account balance at present, with average rates of return, will be worth several million dollars by the time they reach senior citizen age and are ready to begin making withdrawals.

The expense ratio in most years is 0.00%. After the initial positions were established quite awhile ago using a lump sum that was transferred into the account, annual costs are non-existent as I refuse to charge them a fee or any sort of management contract. It is passive investing of the highest order. They had me build them a ghost ship, in effect, that would run itself. The holdings are well-balanced across the economy, global in scale, and would survive another Great Depression even if several of the firms on the roster were wiped out entirely.

Watching the ghost ship sail over time, with me periodically deciding which positions get added, has proven interesting. The thing that strikes me is just how non-intentionally deceptive brokerage house accounting records are. They provide a completely distorted view of what is actually happening with one’s portfolio, overstating the importance of capital gains.

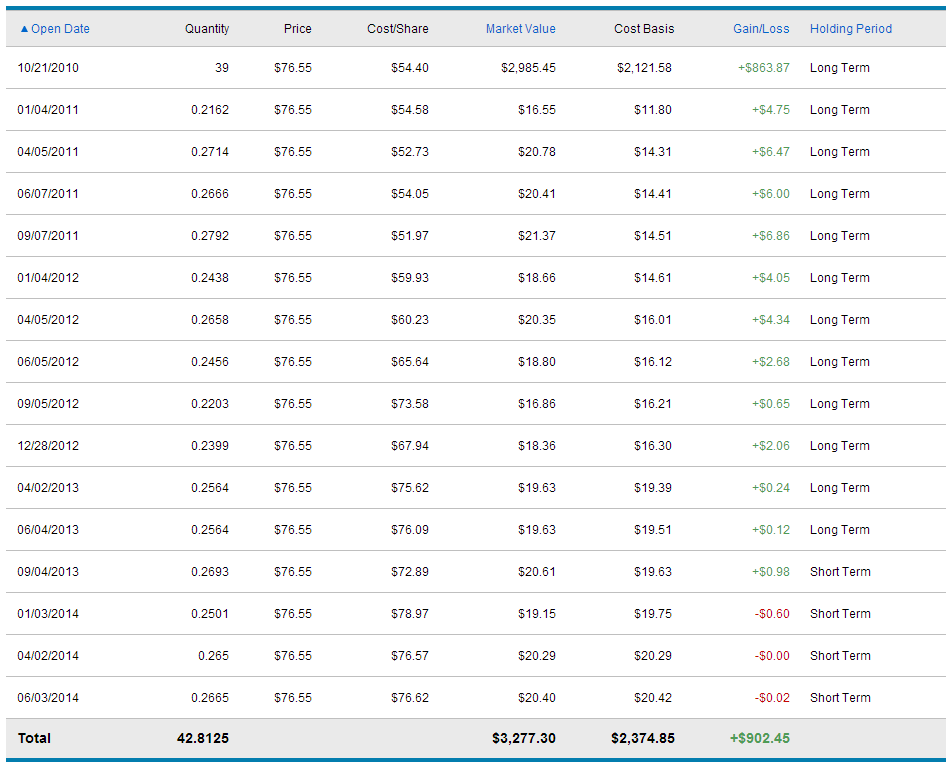

To demonstrate, let’s look at a relatively small position in this account. On October 21, 2010, I used $2,121.58 of this person’s savings to purchase 39 shares of Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. Since that day, Wal-Mart has made 15 cash dividend deposits into their account, which the broker reinvested for free. The combination of additional shares and the board of directors hiking the dividend rates has resulted in the quarterly dividend deposit growing from $11.80 to $20.42 over the 3 years and 8 months that followed.

As as result of dividend hikes and reinvested dividends, you can see that every single dividend received has been larger than the last one. The first was for $11.80, the next for $14.31, the next for $14.41, etc., until, a little more than 3 1/2 years later, the quarterly payout has nearly doubled to $20.42. That’s what you want – a stream of checks that grows on its own without a lot of effort from you.

In that short amount of time, the share count has increased 3.8125 shares, or 9.78%. Meanwhile, Wal-Mart has been buying back a lot of stock so each share outstanding represents more ownership than it did previously, which was partially responsible for the stock appreciating to $76.55.

Given how the brokerage firm calculates return for the investor, this makes it appear as if the profit is $902.45, or 38.00%. But that is not the whole story. That is a rough estimation of the tax basis for capital gains (which, in this case, isn’t even useful since it’s in a Roth IRA).

The real situation is that the account holder is $1,155.72, or 54.33%, richer than he or she was thanks to Wal-Mart. The initial outlay of $2,121.58 turned into $3,277.30 from the following sources:

- $863.87 came from capital gains on the original investment of 39 shares

- $241.51 came from dividends on the original investment of 39 shares

- $11.76 came from dividends on reinvested dividends

- $38.58 came from capital gains on reinvested dividends

While the differential may not seem like much in absolute dollars given the small amount of money in this illustration, in terms of percentage, it is breathtaking. Imagine if we were talking about a $100,000 investment or a $1,000,000 investment. Even worse, this is only a few years into an ownership position. By the time you saw 20 or 30 years, the gulf would be so large that it would completely distort the real world implications of holding the stake.

Why does this happen? The brokers aren’t being dishonest. It has to do with the tax code. The brokerage firm shows dividends as income in the period received so those who hold their shares in plain vanilla accounts can pay their bill to the IRS. From that moment, the dividends are treated no differently than any other source of freshly deposited money for accounting purposes. I know of no brokerage house that accurately tracks total return over time on the month-to-month statements, though a few have tried to move in that direction; e.g., Charles Schwab provides a quarterly portfolio review that gets you there in a round-about way.

Thus, you have a bizarre disconnect between economic reality and accounting figures shown on the brokerage statement. The economic reality is that an owner of Wal-Mart grew his or her money at 54.33%. The accounting figures on the statement make it appear to be only 38.00%. Personally, I have a sneaking suspicion this is how you get the mental disconnect between actual investment experience and perceived investment experience. It’s the reason people don’t understand you could have quadrupled your money with a company like Eastman Kodak despite the stock getting wiped out in bankruptcy.

To fix this, you have to keep records of your own and not rely on the statement in isolation, tracking every dividend check and allocation decision either in a spreadsheet or accounting software. Personally, given my fluency with numbers, I opt to run my household level accounts on a modified form of GAAP using QuickBooks Pro. Every dividend paying company is entered and deposits tracked not only by the issuing company but by sector and industry on the income statement, looking something like this:

This presentation allows me to watch both the trends in cash generation as well as historical sources of dividend income that funded the balance sheet growth. Others of you would be wise to build something like I did for the souvenir shares of Walt Disney I pick up from time to time, watching the dividends received on each lot acquired. (Today is the 59th birthday of Disneyland, by the way.)

I think the brokerage industry needs to find a way to fix this. A lot of people, for better or worse, treat their account statement as their accounting records despite the flaws. For retirees, it can get even more deranged, though still perfectly reasonable once you understand why it is happening. Case in point: While it is nothing special to any of you who are familiar with finance, new investors can often be surprised that in an environment where interest rates have fallen and you are buying a secondary issue bond, you’re going to often pay more than par value so the yield-to-maturity is comparable with new issues at the time. This creates a situation where you are collecting far more interest income than you otherwise should be as the coupon is the same, but you have a built-in loss on the bond so it works out to the appropriate result in the end. You could have an account statement, in certain circumstances, showing a ton of capital losses while you were actually making a positive return. To the non-financially sophisticated, the sea of red can cause panic.

The whole situation could be avoided if I could take over the brokers for a day, or maybe the SEC, and somehow standardize account reporting requirements. This isn’t a hard thing to fix.

Update: I restored this post on 05/05/2019 as part of a project meant to bring back some of the private archives that I feel have educational, academic, and/or entertainment value. However, on May 16, 2019 as part of that same project, I restored another post called An Example of Real World Value Investing Through the Lens of Dr. Pepper Snapple Group, to which I wrote an update detailing the subsequent experience of shareholders. It is a perfect example of why it is a mistake to attempt to use cost basis accounting from a brokerage statement to track investment performance. The summary version is that a single share of stock bought for $47.46 turned into $142.63 of wealth in a relatively short period of time. This was a fantastic return. Strangely, because of how the accounting was structured for a merger with Keurig, the single-serve coffee giant, the stockholder’s brokerage statement would now show an unrealized loss of 38.7%. It seems counter-intuitive that a person could have generated large gains while showing large losses yet that is precisely what happened. I cannot emphasize this point enough. The unrealized gains and losses on your statement are only part of the story and often can be misleading. You must measure actual economic results in the form of total return.