In honor of the new energy portfolio I’m setting up for my family, I thought I’d do a 25 year case study of an investment in Chevron common stock. The point is to illustrate how the biggest, most boring companies on the planet are not, in fact, so boring when you look at the remarkable things they achieve for civilization and the huge returns they earn for shareholders.

Imagine you wake up back in time, 25 years ago. It is April 23, 1988. You have a pile of $100,000 in cash and have to make an investment decision. You decide to buy an ownership stake in Chevron, the oil giant. Chevron was the product of the consolidation of three of the original “Seven Sisters” that, together, controlled 85% of the world’s oil production (the three under its corporate umbrella were Gulf Oil, Standard Oil of California, and Texaco).

When the stock exchange opened that morning shares of Chevron were available for $46.00 each. You were able to buy 2,173 shares and paid a small commission. You locked the stock certificates in a bank vault and ignored them, cashing your dividend checks every quarter.

Chevron owns everything from oil wells to refineries. It is one of the largest oil giants on the planet, well known to virtually everyone, and about as high profile as you can get in the energy industry. Anyone, from school teachers to widows, doctors to accountants, could have bought shares at any time in the past quarter century without much trouble and without much risk given the enormous stable base of earnings and assets underlying the enterprise.

How did your decision turn out when you arrive back at the present day? During this period, oil prices went from $10 to $130 or so, all the way back down, again. It was volatile, to say the least.

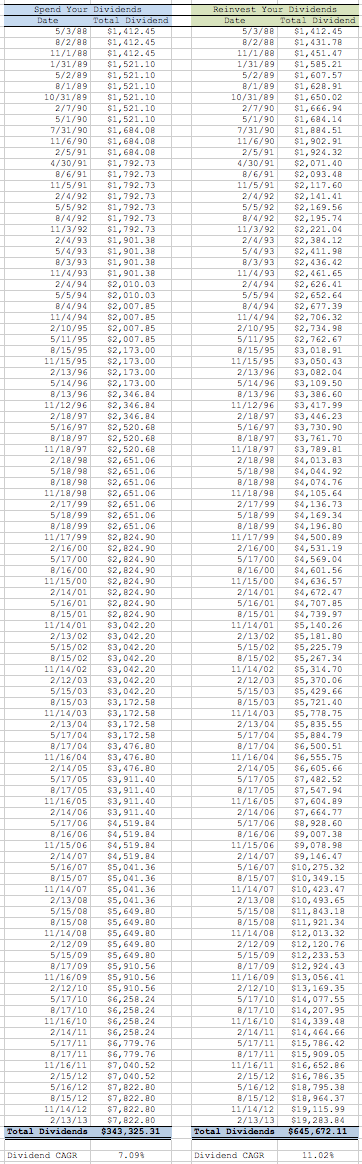

Let’s look at two scenarios. In the first, you spend all of your dividends along the way. In the second, you reinvest all of your dividends.

Chevron Case Study Scenario 1: Spending Your Dividends

When you go to open you safe deposit box, you find:

- The bank vault holds $1,021,049.24 of Chevron stock (8,692 shares at $117.47 per share)

- You would have cashed dividend checks worth $343,325.31 over the years – money that was deposited into your checking account to spend on vacations, furniture, clothes, education, gifts to family and friends, charitable donations, debt reduction, new cars, real estate, other investments, or whatever else you desired.

- Grand total: $1,364,374.55* for a compound annual growth rate of 11.02%

That’s not even the best part. Chevron now pays an annual dividend of $3.60 per share in cash. You own 8,692 shares, so you can expect, going forward, an annual income of $31,291.20 from your ownership of the enterprise. That money shows up each year, even if you never get out of bed in the morning. When you pass away, you could put the stock in a trust fund for your children and grandchildren, and that money would still gush in for them to use, paying for college or living expenses.

Chevron Case Study Scenario 2: Reinvesting Your Dividends

For now, we will assume that you made the investment in some sort of tax shelter, because it would be almost impossible for me to run dozens of scenarios under multiple Federal, state, and local tax laws; a project more appropriate for a professor of finance with a team of graduate students at his command.

Every quarter, when your Chevron dividends arrived, your money was plowed back into more shares of Chevron at the closing price on the dividend day. When you go to open the safe deposit box, you find:

- The bank vault holds $2,536,577.24 of Chevron stock (21,593.4046 shares at $117.47 per share)

- Grand total: $2,536,577.24 for a compound annual growth rate of 13.81%

Even better, your 21,593.4046 shares of Chevron stock each are entitled to a $3.60 dividend this year. That means your annual income from the investment will be $77,736.26.

Analyzing the Difference Between Not Reinvesting Your Dividends and Reinvesting Your Dividends in Chevron

If you didn’t reinvest your dividends, you were mailed $343,325.31 in cash over the years that you got to enjoy.

[mainbodyad]If you did reinvest your dividends, your dividends were used to buy more stock, with those new shares also generating dividends, creating a virtuous cycle of wealth building. Over the 25 years, you actually collected $645,672.11 in cash dividends. Of that, $343,325.31 came from the dividends on your initial $100,000.00 investment, while $302,346.80 came from dividends on dividends on dividends et cetera. That $645,672.11 was used to buy you an extra 12,901.4046 shares of Chevron stock, which have a market value of $1,515,528.00. Backing out the $343,325.31 you would have gotten to enjoy had you spent them, we can calculate that $1,172,202.69 of extra wealth came from your decision to reinvest the dividends, rather than spend them.

In other words, you had a choice. Depending on what your policy was when it came to your Chevron investment, you experienced one of the following two outcomes:

- In the first scenario, you put $100,000 to work for you, got to spend $343,325.25 along the way, and now have $1,021,049.24 sitting in a bank vault. Your annual cash dividend income is $31,291.20. Your money compounded at 11.02%.

- In the second scenario, you put $100,000 to work for you, spent nothing along the way, and have $2,536,577.24 sitting in a bank vault. Your annual cash dividend income is $77,736.26. Your money compounded at 13.81%.

Here is what the rough breakdown of the quarterly dividend income stream looked like in both scenarios.

The stock price fluctuated wildly during some periods in this chart. Yet, the investor who focused on the checks he was receiving, reading the annual report every year and making sure that the trend line was going up over time, at the very minimum keeping pace with inflation or, even better, exceeding it, did just fine. He thought like a private business owner and was rewarded commensurately.

As an interesting note: Had you not reinvested your dividends, you would have received your initial $100,000 investment back by 05/17/2000. After that, any shares of stock you owned, and any additional dividend income was “free money” in a sense. (From the economic perspective, it wasn’t because you have to factor in inflation and the compensation to which you would be entitled for risking your capital in the first place, but to the laymen, you got your hundred grand back and now you still own the stock and continue to collect dividends.)

If you had decided to reinvest your dividends, your cash dividend income would have paid back your initial $100,000 investment by 05/18/1998.

As I’ve repeatedly told you, there is no right or wrong answer. Neither scenario is inherently better than the other. They are different, with different benefits and different opportunity costs. It is further complicated because under the first scenario, you might have taken the dividends and invest them in another business, which would then need to be calculated as a side-by-side comparison based on its performance relative to Chevron to determine whether it was a wise capital allocation decision. Likewise, an investor who passed away earlier than expected would have gotten much more utility out of the first scenario, as would an investor in an alternate universe where Chevron went bankrupt as the cash dividends would have provided a substantial return just like they did in the case of the Kodak bankruptcy.

In any event, this is what winning looks like. Tiger blood. Charlie Sheen.

Life with Chevron is good.

Investors ignore businesses like Chevron every day. They are boring. They never look like they do anything. Had you opened the newspaper, it never would have looked like the stock moved beyond the $40 to $120 range as the board of directors seems fairly consistent about splitting the stock whenever it gets too high in nominal value. The dividend yield always looked good, but not excessively rich, making up for in growth what it didn’t offer in yield. It was the perfect dividend growth stock.

[mainbodyad]And even more interesting? The market crashes were the times that made you the most money in the second scenario because your reinvested dividends bought more shares when the stock price was depressed. The global economic collapse of 2008-2009 created a lot of additional wealth for you as the stock fell substantially, allowing you to gobble up shares at very attractive valuations. For a dividend growth investor reinvesting his or her dividends, stock crashes are wonderful, stock booms are bad.

I have not, yet, but I do plan on adding shares to the new KGEP plan sometime.

* Footnote: Interestingly, from an economic perspective, this is somewhat deceptive. It simultaneously understates, and overstates, your returns. On one hand, you spent your cash dividend income along the way. Your dividend payments in the past had far more purchasing power than they do today, making them more valuable than they appear. After all, every $1.00 in dividend income you received in 1988 is the same as $1.91 of dividend income today. On the other hand, $1,013,226.44 in ending market value is the inflation-adjusted equivalent of $520,027.33 in 1988 terms. You would also have some tax considerations, depending on how you held the stock and whether or not you had any tax shelters. Regardless, you still did very well. Chevron was the gift that kept on giving during these 25 years as people heated their homes, put gas in their cars, and fuel in their jets.