Borders Group: The Single Dumbest Investment We Ever Made

Due to our disciplined value investing philosophy, coupled with our insistence upon diversification of income and assets, we haven’t experienced a lot of big losses. When we do, we try and study what went wrong so we can understand if there was a structural problem or a blind spot in our mental cognition that should be avoided in the future. We never want to have to “return to Go” in Monopoly terms. That is just intelligent portfolio management.

Due to our disciplined value investing philosophy, coupled with our insistence upon diversification of income and assets, we haven’t experienced a lot of big losses. When we do, we try and study what went wrong so we can understand if there was a structural problem or a blind spot in our mental cognition that should be avoided in the future. We never want to have to “return to Go” in Monopoly terms. That is just intelligent portfolio management.

On the whole, we’ve done almost everything right. There were a few mis-steps along the way, but they were all small relative to total capital. In our regular portfolio, the single biggest loss in percentage terms was our position in Borders Group, the nation’s second largest book retailer. I’d love to blame someone else but the bottom line is, the error was and is completely and totally mine. The screw-up was royally huge. I just didn’t move fast enough, or rather, sat around “sucking my thumb” as Charlie Munger would say.

What is particularly frustrating is that the underlying thesis of the investment wasn’t the problem, I just didn’t factor in macroeconomic and technological forces that were working against us, even though I knew of their existence. I saw a horse and buggy manufacturer that was cheap and was tempted. Even now, looking back at the data, we could have made a ton of money. But we didn’t. That is why Benjamin Graham insisted on buying stocks like underwriting insurance – you never know when one of your positions is going to self-destruct. It will happen from time to time. But it shouldn’t derail your long-term compounding.

(It reminds me of a story an insurance executive once told Warren Buffett. He got so tired of his subordinates saying, “We would have had a great year … except for.” that this executive said he was going to create a new subsidiary called the “Except For Insurance Group” and just put all of that year’s losses in it so that way, they could say, “Our main insurance business made huge profits, but our Except For division is terrible, as usual.”)

The History of Our Borders Group Investment

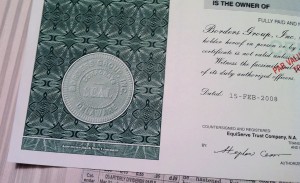

Between 2001 and 2006, Borders Group had undertaken a massive share repurchase program and bought back a net 22.63 million of its shares, reducing the total shares outstanding from 81.2 million shares to 58.57 million shares. That meant every share now represented 38.63% more equity in the company than it did before the stock repurchase program.

Between 2001 and 2006, Borders Group had undertaken a massive share repurchase program and bought back a net 22.63 million of its shares, reducing the total shares outstanding from 81.2 million shares to 58.57 million shares. That meant every share now represented 38.63% more equity in the company than it did before the stock repurchase program.

During the same period, sales grew from $3.388 billion to $4.114 billion. But the company had experienced the unfortunate side effect of “operating leverage”, which means a business has high fixed expense level under which everything is a loss and over which most sales drop to the bottom line as profit. As a result, profit had declined from $109.3 million to $22.6 million.

Shortly thereafter, Borders Group brought in George Jones, an executive from the highly successful Target retail chain. He began to drastically reduce inventory, free up working capital, shore up short-term cash needs and, later in 2007 and 2008 when the recession was looming on the horizon, shut off all capital expenditures far earlier than any other company we followed. He knew his stuff. The man “got” retail – and even my father was impressed with him (remember my dad helped build a seven-figure sporting goods store from the ground up decades ago with no starting capital or connections so he understands the retail game better than most people).

Furthermore, Jones negotiated far more favorable terms with vendors and ended the Borders Group deal with Amazon.com. Why, after all, should Borders be giving sales to Amazon? People should buy from it, be able to pick up in local stores, etc. They began developing a revamped Borders retail site.

We figured that if Borders could do nothing but get back to its previous net income level, the reduced share count would more than offset the debt incurred to repurchase the shares and earnings per share, or EPS, would skyrocket. At the time, Borders stock had fallen from $25 per share to $13.50.

We figured that if Borders could do nothing but get back to its previous net income level, the reduced share count would more than offset the debt incurred to repurchase the shares and earnings per share, or EPS, would skyrocket. At the time, Borders stock had fallen from $25 per share to $13.50.

We began buying, paying as high as $16.50 or so, but mostly picking up shares at $13 and below both for the operating companies and the personal accounts of various family members. We were, in effect, betting on the ability of George Jones to turn around Borders to be merely as successful as it was a few years prior. All we needed was mediocre performance and we figured we’d get a decent bump out of the share price for a nice double-digit return.

Plus, the valuation had reached such a low level that the entire Borders Group was being valued for less than a handful of European stores the company had sold a few years prior along with a contract it had that gave it the right to sell the Paperchase subsidiary. In effect, the market was valuing the main Borders chain of stores at $0. We didn’t need much to go right – just something – and we’d make money.

Oh, and there was one more piece of icing on the cake: One of the biggest hedge funds in the United States had a major position and wanted to find a way to sell the business, putting it on the auction block.

Disaster Strikes Borders Group

And then, with one fell swoop, everything outside of Borders Group went wrong, causing the company to enter a near-death spiral that slashed book value from $1+ billion to $250 million as losses mounted everywhere. I mean, the entire world fell apart.

- Apple iPhone was released, further cementing the iTunes music delivery store and turning CD sales, which had been a big part of the Borders Group business, into a money losing black hole. The music sections had to be taken out of the stores.

- The credit crisis hit, money couldn’t be had, and Borders needed to refinance $40 million in debt in under a year at a time when no one could borrow money because AIG was collapsing, Lehman Brothers was melting down, Bear Sterns was imploding, and the financial world was coming to an end. This made the markets believe that Borders Group was looming on bankruptcy.

- Amazon.com released the Kindle, allowing customers to take wireless delivery of books on a hand held device, further cutting into profits to the point that the operating leverage threshold was reached.

- Mall traffic dried up, taking with it Borders Group’s smaller subsidiary, Waldenbooks, which was liquidated.

- The United States then entered the greatest economic down turn since the Great Depression, unemployment doubled, and discretionary spending shut off overnight, almost taking down the main Borders business. Barnes & Noble indicated it had no interest in a takeover of the firm, leaving it to fend for itself as the entire world tried to batten down the hatches for the hurricane that was raging around everyone.

We Finally Throw In the Towel on Borders Group

In 2009, we sold virtually all of our shares in the firm, some for as little as $0.54 per share. I’ll save you the trouble of getting out your calculator: That is a loss of 96.73%. This created a tax loss asset on the balance sheets, though, so the real loss was 62.88% after backing out the money we saved in Federal and state income taxes due to the write-off.

In 2009, we sold virtually all of our shares in the firm, some for as little as $0.54 per share. I’ll save you the trouble of getting out your calculator: That is a loss of 96.73%. This created a tax loss asset on the balance sheets, though, so the real loss was 62.88% after backing out the money we saved in Federal and state income taxes due to the write-off.

As we discussed what went wrong so we could study and learn from the experience, my mother (who owned shares in the particular private business through which I acquired much of the Borders stake) stopped us all, shrugged her shoulders and said: “Our idea was good, things just went wrong because Borders was hit with the greatest recession since the Great Depression. We’ll make it back. It isn’t a big deal.”

The lesson we learned can thus be summed up as:

- A bad business that requires a lot of capital, earns a low return on book value and faces technological obsolescence cannot be redeemed simply because it is cheap. We would have been better off paying a fair price for a good business like Wal-Mart, which we also owned at the time.

- We had acquired shares too quickly, not giving the market enough time to give us a more favorable price. This led to shares being concentrated more heavily in some our of accounts than others, making the losses uneven.

- Sometimes even talented management, like Jones, cannot overcome macroeconomic forces.

Even more important than any of that, though, we learned that:

- Our business model is the right one. Even as the Borders losses hit the balance sheet, the profits from trading bank stocks (particularly the safer banks, Wells Fargo and U.S. Bancorp) were rapidly increasing and our operating companies were generating more cash to fill the hole.

The good news is, the Borders Group position wasn’t huge. We managed to escape with manageable losses that weren’t a big part of our net worth. In fact, as I mentioned, the actual net loss was much lower because we received write-offs, deductions and tax-loss carry-forward assets from the IRS. But given the percentage drop, I consider it the worst investment mistake we’ve ever made. I was 25 or 26 years old and had bought hundreds of stocks since I first began as a kid. Nothing had even come close to that kind of percentage wipe out.

To this day, when I walk into Borders and take out my American Express card to buy books, it takes every ounce of my self control not to look at the cashier and say, “You know, I could have bought every single item in this store with the money I put into you guys. Every single item. So how about you throw this one in for free?”

But how can I complain when the mistake was, and is, 100%, totally, completely and obviously mine? A man has to own his mistakes. I screwed up on this one and watched a lot of beautiful investment capital just melt away in front of my eyes. However, in the long-run, it is a blip on our record. Why? Because we think about avoiding wipe-out risk all the time. We work to protect our assets by segregating investments, lowering our exposure, having trademarks and copyrights guarded by a great law firm, avoiding leverage, and living a comfortable, but moderate lifestyle so that we don’t have a lot of “silly needs” as Charlie Munger says.

In fact, if I had never written this case study, we could have buried the entire Borders investments in the footnotes of history because it will be dwarfed by the businesses through the long-term power of compounding. Sort of like Buffett did when he bought into that gas station and lost a ton of money in his twenties. No one would have known. But if it helps even one of you learn, we feel we owe it to share as a way of saying thanks for the intellectual generosity of those value investors who have come before us.