An Accounting Homework Assignment for Those of You Who Want to Learn to Analyze Businesses

I get a lot of requests for real-world examples or homework assignments that have to do with some of the more important investing concepts. This morning is your lucky day if you’re fairly new to the finance game and want to give diving into SEC filings or annual reports a try. Here’s a (fairly) easy introduction to how things can appear better, or worse, than they really are. Ready? Let’s go.

The scented McCormick annual report – one of those small, happy things to which I look forward every year – showed up a week or two ago and Aaron brought it to me the moment he realized what it was. This year, the ink has been infused with the fragrance of Shawarma spice blend from the Middle East, made up of cumin, black pepper, clove, cinnamon, paprika, turmeric, ginger, coriander, and garlic. It took me awhile to get through the numbers because it’s such a wonderful sensory experience that I find myself distracted, pressing my face into the paper and breathing deeply.

Before I say what I’m about to say, and give you the assignment I’m about to give you, understand the underlying economic engine of McCormick is incredible. (That is one of the reasons I’m going to pick on it. It can take it.) The spice king is easily one of the top 100 highest quality compounding engines in the publicly traded markets anywhere in the world today. Very little has changed in its advantages over the three different centuries in which it has conducted operations. If you forced me to hold 10% of my family’s net worth in it for the rest of my life, I wouldn’t lose a moment’s sleep given the probabilities of long-term success and the inherent advantages it has that put it exponentially ahead of its second biggest competitor.

Case in point: Its earnings quality is good (accruals relative to net income are in-line with peers and overall nothing crazy so there isn’t a lot of aggressive accounting happening from what I can tell). Its operating earnings after interest expense but before income taxes relative to average tangible capital employed comes in at ~25%, putting it in the “excellent business” category. If we were to enter a sustained period of inflation, it should be able to survive it with purchasing power intact far better than other businesses like the steel mills I mentioned the other day in one of my About.com articles, because they require a lot less invested in property, plant, and equipment for every dollar generated for owners. (That may not seem like it matters in the world in which we now find ourselves but over a 25-50 year period, it translates into a major advantage; an ace in the back pocket that provides one more source of long-term protection even if your shares are down 50% in market value at any given moment.)

Shares of McCormick sit in my own, personal, retirement accounts, and I have ownership shoved in practically every single retirement account I control for family and friends. Like Nestle, it is one of those deceptive businesses in that it never seems to cause excitement in the short-run. One year, five years go by and the stock is still just there, doing its thing. Yet, you look back 10, 15, 25 years and you suddenly have these huge compounding advantages that cause you to wonder, “Where did all of this originate?” It’s the magic of doing a little bit better than average for long stretches of time.

None of that has changed. I’m crazy about the place. I have no intention of selling my shares and will almost assuredly be a net purchaser of McCormick stock for the remainder of my lifetime, present known factors considered. I will also, at some point, likely add them to the custodianships I established for my nieces and nephews so they become owners, too.

All of that out of the way … there is something that bugs me about McCormick. I am not a fan of how they have been using their share repurchase plans over the past few years or, rather, how they brag about share repurchases that don’t translate into meaningful reductions in outstanding share count despite management constantly talking about record buy backs. To explain what I mean, we’re going to have to delve into some figures. Here is a simplified summary I put together showering the after-tax profit, dividends, and buybacks over the past 36 months. The last row is the sum of the dividends and buybacks, or the total amount returned to owners in one form or another.

| Description | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 36 Month Total |

| Net Income | $437,900,000 | $389,000,000 | $407,800,000 | $1,234,700,000 |

| Dividends | ($192,400,000) | ($179,900,000) | ($164,700,000) | ($537,000,000) |

| Buy Backs | ($244,300,000) | ($177,400,000) | ($132,200,000) | ($553,900,000) |

| Total Returned to Owners (Dividends + Buybacks) | ($436,700,000) | ($357,300,000) | ($296,900,000) | ($1,090,900,000) |

Now, let’s look at the average diluted shares outstanding over this same period.

| Description | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 |

| Average Diluted Shares Outstanding | 131,000,000 | 133,600,000 | 134,300,000 |

Huh. Okay.

This puts the total reduction over the past 36 months at 3,300,000 shares, or a mere 2.46% of the starting total. To state it in sort of a non-technical term (that wouldn’t work under all conditions so be careful about extrapolating it to other situations), for every 1 share outstanding McCormick actually destroyed, net of all other factors, it appears as if it spent $167.85 of owner money at a time when the stock price was between $49.90 and $77.10 (we’ll see later, this actually isn’t the case but we’re not to that point in the discussion, yet. For example, they could have had an equity issuance to raise money so even though share count didn’t fall, there was a ton of cashing sitting around from the proceeds; they could have issued stock options, which means they’ll collect the exercise premium; they could have had convertible debentures, which would have resulted in the reduction of liabilities and interest expense, offsetting these numbers; we don’t know, we have to investigate). On a firm-wide basis, the market capitalization ranged from a low of $6,620,732,000 to a high of $9,945,900,000. Even if all of the stock buy backs had been repurchased in 2014 at the absolute highest market capitalization during the time frame – an impossible worst-case scenario which we obviously know isn’t true given the annual totals – the reduction in shares outstanding should have been at least 5.57%, or twice the 2.46% that actually occurred.

Something is going on and we need to get to the bottom of it. Where is the missing money or source of the additional shares? Unlike a firm such as AutoZone 10 years ago, it wasn’t buying back stock so aggressively that there was a distortion in the weighted average share count (read: The GAAP formula wasn’t lagging the actual share count by a large enough margin to explain such a huge disconnect.) Somehow, McCormick was printing new stock certificates at a rate that had a material impact on the pace of net reductions; that rendered a large part of the headline buy backs moot. This could be fine – and have a perfectly acceptable, even desirable, explanation1 – but management should not be boasting about spending almost half a billion in buybacks if a relatively small amount of that translated into greater ownership percentages on a per share basis absent some mitigating circumstance.

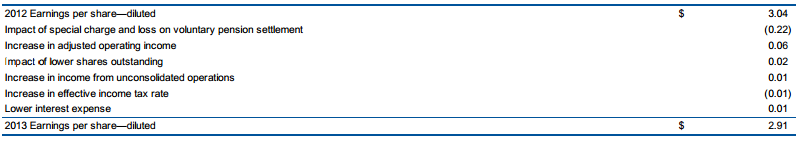

Pulling up the Consolidated Statement of Shareholders’ Equity we see that a mystery is a foot because the total buy backs don’t match up with the actual shares repurchased and retired. We also see buried in the numbers net share reductions are having a relatively small absolute effect on the year-to-year changes in diluted EPS. Here is 2012-2013:

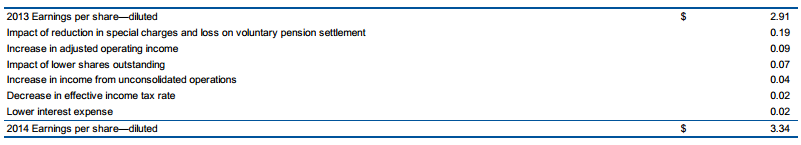

Here is 2013-2014:

Confronting this mathematical puzzle, your inner security analyst should should have been triggered. Skepticism should have risen from the very depths of your soul. Something isn’t right. Allow me to re-enact how the scene played out at my desk the first time I saw it …

Could it be that they completed a major merger or acquisition, buying out a competitor and using a tax-strategy pioneered on a large scale roughly a decade ago when Procter & Gamble announced they were buying Gillette? That deal involved paying for the acquisition with stock so the owners enjoyed a tax-free exchange, then specifically, ruthlessly, purposely buying back an equivalent amount of shares in the subsequent years, often through the open market, to offset the dilution and give the corporation itself the advantages of a cash transaction.

We investigate. Buried in the annual report, we find that the only acquisition during this period was in 2013. McCormick purchased Wuhan Asia-Pacific Condiments Co. Ltd., a privately held Chinese business, paying $144.8 million. This was achieved using $142.3 million in cash, net of closing adjustments, plus the assumption of $2.5 million in debt. The money was raised using funds on hand plus proceeds from newly issued debt. (McCormick has a habit of buying businesses, temporarily levering up ever-so-slightly, then paying off that debt quickly to bring the metric it watches – a non-GAAP figure that takes total debt relative to adjusted earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization – back into the historical range management believes is prudent, 1.5 to 1.8. This is among the reasons it has one of the stronger balance sheets in its industry.)

Alright, so no. No major acquisition paid for with stock.

Were there any convertible debentures or other odd security issuances, such as warrants, tied to a capitalization structure change?

No. Nothing like that.

This leaves only a handful of possibilities. Your homework:

- Go to this page and download the 2014 McCormick annual report (it includes the 10-K)

- Identify where all of these new shares that offset the share buy backs originated

- Identify how much, if anything, McCormick was paid for those shares being issued

- Determine whether this situation has any meaningful influence on the intrinsic value calculation

- State the lesson. What moral should investors take away from the figures? How, if at all, should this change your investing behavior or allow you to lower your risk when building a portfolio?

Should you fail … don’t. I believe in you. This is something you need to know how to do if you’re analyzing a business.

If you’re feeling generous, leave your answer in the comments for others who decide they can’t figure it out to use as an answer key. Even seeing how you did your work, or what to look for in the filings, can help someone else. Remember where you were early in the journey and give someone a helping hand like you would have wanted early in your investing career.

Footnotes:

1 If the stock is fairly or overvalued (which it appears to be), McCormick & Company compensates employees with options that have exercise prices equal to the market value at the time of issuance (which it does), the vesting period is relatively short (which is the case for many of the issued stock options), and management is committed to buying back any shares that are ultimately issued under the plan (which seems to be the case), this compensation system can have the wonderful real-world result of owners taking on less risk. If things work out well, the employees get paid little more than they would have been paid, anyway. If things work out poorly, the compensation never gets paid at all, mitigating the damage.