By now, all of you know what happened recently with the Swiss Franc, Euro, and, as an extension, the price change of Nestlé shares in the United States. It caused a stream of messages to come in through the contact form like I haven’t seen in a long time, all with the same theme. Here are just two, randomly chosen, that sum up the gist of what my inbox looked like on January 15th and 16th.

First off, I would like to thank you for your time and for being so willing to share your knowledge of business and economics with all of us complete strangers. I’ve been a near daily visitor here for a couple of years and have learned a great deal from your posts.

My question for you is: Could you walk us through why removing the Euro peg caused Nestlé‘s ADR to increase by 6% in USD? I get why its’ shares dropped in CHF – although the magnitude of the drop seems extreme given how much of their costs and revenue is not in CHF – but cannot wrap my mind around the USD increase. What am I missing here?

Thank you,

Brett

Joshua,

Could you kindly explain the Swiss Franc issue in layman’s terms? I think currencies are generally confusing to novice investors like myself.How said currencies affect company profits (and share prices) is the other main question, along with how this all translates across the pond into ADR prices for Swiss companies. My rudimentary understanding is that although Nestlé‘s price on the Swiss exchange fell by 10-15%, it’s ADR price went up by the same. This is confusing black magic to many of us!

Thanks for the great site – your insights and wisdom are much appreciated.

Sunil

Given the interest in the topic, I thought I’d take some time to sit down and provide a basic overview of what is happening. Please keep in mind this is grossly oversimplified. I’m going to gloss over some of the technical details to give you a big picture view of what is happening and how you, as an owner, might think about it. This will serve as a nice follow up to our discussion on foreign currency and international investments from back in December.

Picture a World in Which You Love Making Money from Selling Macarons

Imagine you live in Switzerland. You love macarons. They are your life. The colors; the flavors. You decide to open a small macaron shop to experience the ecstasy of transforming base ingredients into wealth as people pay you for a bite of happiness, conveniently measured at 43 CHF per dozen.

Your little shop expands, does very well, starts serving coffee, branches out into catering, and before long, it earns 1,000,000 CHF per annum after taxes. You are a macaron legend. Your business is valued at 12x earnings, giving it a market capitalization of 12,000,000 CHF.

You start a macaron business in Switzerland. You sell these delicious, colorful, and expensive desserts.

Houang Stephane, M Le Macaron, Macaroons from Bordeaux (France) from Flickr.

Image made available under Creative Common Attribution 2.0 Generic License

Last year, an American investor offered to buy your 12,000,000 CHF business. At the time, it would take $1.00 from the United States to purchase 0.91 CHF, so he would need to convert $13,186,814 to complete the purchase. You agreed, and now work on salary with a giant pile of money in Swiss bonds that pay you interest income. That way, you can focus on the macarons and not the business.

Twelve months later, in January of 2015, Switzerland surprises the world and announces it is giving up on the hopeless attempt to implement price controls by artificially pegging its currency to the Euro. The free market reacts and the Swiss Franc moves relative to other global currencies based on what people believe is the underlying intrinsic value. By the time the dust settles, $1.00 will buy only 0.8794 CHF. It’s not a huge change because the U.S. dollar was already so strong thanks to the gargantuan size of the American empire and its (relatively) rock solid balance sheet.

[mainbodyad]Even though your business still earns exactly 1,000,000 CHF per year, and is valued at exactly 12,000,000 CHF, the American investor, who is measuring his results based on purchasing power in his own country, has to carry to value of your shop at $13,645,668. This has the position up $458,854 even though there has been no change in the underlying intrinsic value of the bakery of itself. It still owns the same assets. It still generates the same profit. However, unless our American investor flies to Switzerland and spends the money there, he is going to have to translate it back into U.S. dollars. At the moment, given the Franc is stronger relative to the dollar, it means he’d enjoy a bonus of $458,854 were he to sell his stock.

If he intended to hold onto your bakery and cafe for generations, passing it on to his children, slowly expanding through Switzerland, and keeping it as a family enterprise, those year-to-year fluctuations don’t mean much. He is interested in the total number of units you are selling, the total purchasing power you are acquiring, and the total resources you are amassing by trading your talent for transforming sugar and egg whites into claim checks on society.

Now, Picture a World in Which Your Macaron Business Had Half Its Earnings Generated in Paris

Imagine a slightly different scenario. You still opened your pastry shop and cafe, you still sold it to an American investor, and you still earned 1,000,000 CHF in profit the year before last. Only, half of your earnings came from a location in Paris, generating Euros, and the other half from your Swiss-based location, generating Swiss Francs.

You report your profits in Swiss Francs because that is your home country, but, really, what you ended up with was 500,000 CHF + €408,730. Last January, you converted the €408,730 at a 1.00-to-1.2233 rate back into 500,000 CHF, bringing you to 1,000,000 CHF total. Thus, at 12x earnings, your business is still valued at 12,000,000 CHF.

The Swiss central bank decided to let the free market set the exchange rate between Swiss Francs and Euros. Since the Euro is worth far less than it had been forcing people to pay for it, its value relative to your home currency collapses. This year, if your volume and costs remain exactly the same, you are still looking at earning 500,000 CHF + €408,730. You sold the exact same number of macarons in Zurich and in Paris, at the exact same price, with the exact same costs.

Only, now, since your accounting statements are reported in CHF, you have to translate that €408,730 back at the new exchange rate of 1.0207 CHF for 1.00 EUR. That means your €408,730 gets put on the income statement as the equivalent of 400,441 CHF.

You add up your Swiss profits of 500,000 and your pretend like you converted your Euro profits into 400,441 CHF and get 900,441 CHF.

Even though your volume was exactly the same, and your earnings engine pretty much identical, you show a 99,559 CHF reduction in net income, which rounds up to 10%.

Your 12x earnings valuation is applied to the 900,441 CHF you generated and now your company is valued at 10,805,292 CHF not 12,00,000 CHF. Roughly 1,194,708 CHF has gone up in smoke.

Across the Atlantic Ocean, your American investor is looking at his portfolio. His stock is worth 10,805,292 CHF. Only his translation rate back to the U.S. dollar has also changed. In this case, recall that the Swiss Franc strengthened a few percentage points relative to the dollar so when he converts the position value back to his home country to determine how well he is doing, it is carried on the books at $12,287,118. To him, the value of the holding has dropped only $899,696. That is 6.8%, a number far more attractive than nearly 10%.

Nevertheless, not a lot has changed. In Paris, your manager is earning the exact same amount of money, and the subsidiary is valued exactly the same in Euros as it was prior to the currency move. In Switzerland, at the parent company level, you sold the exact same number of macarons and cups of coffee as you had the previous year. In the United States, it’s business as usual. In fact, if you paid a small dividend in CHF, the American investor will actually get a raise of 3% to 4% on the distribution, which you could fund from the Zurich profits that were sitting in CHF. It all looks very noisy but your business is still rolling along, producing what it always has produced.

What Are the Economic Implications for the American Investor?

In practical terms, the American investor’s position depends on his reasons and time frame for holding the macaron and coffee business you’ve built. If he wants to eventually expand around the world, open locations in New York and San Francisco, Hong Kong and Seoul, the fluctuations aren’t particularly meaningful. With each passing year, he just needs the business to have a higher net worth, higher earning power, more unit volume, and perhaps better market share. The exact amount of year-to-year increase in intrinsic value isn’t particularly useful to know provided it’s going in the right direction at a satisfactory rate. As long as there isn’t a currency disaster like Venezuela experienced after the socialists destroyed the economy, most of it should wash out in the long-run even if it can’t be perfectly measured. Part of this comfort comes from the fact you aren’t using debt. It’s easy to take the long view when you hold fully paid for, settled, non-pledged equity. You don’t have to be smart, you just have to be patient.

Being financially savvy does have its perks. In fact, the ordeal can actually turn out to be a huge advantage. As long as the balance sheet is strong, and the business non-impaired, the investor can order the Swiss Franc profits sitting in Zurich transferred to the now cheaper Euros to buy up competitors around Paris, essentially getting a double-digit discount on the acquisition cost. If things ever revert, he can ship those earnings back to Switzerland and expand there, instead. If the U.S. dollar becomes strong, he can infuse more money into the business from his home country of the United States. There are always intelligent things to do.

With the Swiss Franc strengthening against the Euro, despite lower reported profits, the macaron and cafe business could take advantage of the situation by moving money from Zurich, in CHF, to the now cheaper Euros, acquiring competitors in France at a discount.

Louis Beche Macaron I from Flickr. Image made available under Creative Common Attribution 2.0 Generic License

The story is different if he needs to sell the macaron business sometime in the next five years, or uses that dividend stream to pay his mortgage. Then, what would have been otherwise benign currency adjustments can have devastating personal consequences if he finds himself caught at the wrong time in the wrong position.

What All of this Means for Nestlé Stockholders Following the Huge Fluctuations in Currency and Share Price During the Past Week

With all of that in mind, imagine your macaron and coffee business is, in fact, a $250+ billion global empire working in dozens of effective currencies and almost every nation on Earth with subsidiaries and supply chains spanning all corners of the planet. Your financial statements are reported in CHF but your investors exist everywhere and are constantly seeing fluctuations not only in share price, but in the quoted market value of their holdings based on the currency translation price between CHF and their home country.

To understand what just happened in the chaos of last week, you have to realize that Switzerland is a marvelously run country in comparison to most other places. It has a constitutional amendment that makes it difficult for politicians to run up the national debt. It’s stable. It has a lot of great businesses and a highly educated, scientifically minded population. It’s small enough that the financial policies can be targeted in a way that benefits most of the population unlike the Eurozone where what is best for a nation like Germany is in direct contradiction with what is best for a nation like Greece. It hasn’t been in a war in a couple of centuries (between the mountains and every man over the age of 18 being issued an assault rifle or pistol, who would want to try to invade?). It has a rock-bottom unemployment rate. Inflation is modest. There isn’t a lot of class or social conflict; at least not to the degree you see elsewhere.

These things are not true for some of the different cultures and countries on the European continent. What this means is that the Swiss Franc has a persistent habit of appreciating against other currencies because people are mostly rational. They look around and realize that money held in Swiss Francs is likely a lot safer than money held in other currencies. This can be a challenge for international businesses headquartered in Switzerland because it means moving foreign profits back home results in less purchasing power; debt incurred domestically becomes a bigger burden if being repaid in foreign earnings; it makes exports much more expensive, which can reduce sales and cause unemployment as domestic factories lay off workers who are no longer necessary due to declining unit volume.

[mainbodyad]To get around this, and for various other reasons, the central bank of Switzerland decided back in 2011, when Europe was having all sorts of problems and people were fleeing to the Swiss Franc for refuge, driving up its value, that it wanted to artificially manipulate the market so that 1.20 CHF would always convert to roughly 1.00 EUR. By pegging the two monetary units together, they hoped to help their own domestic businesses and remain competitive in European markets. Swiss businesses and investors appreciated the stability in exchange rates.

Right about now is the time you insert the old economist’s joke, “Remember that time when price controls work? Neither does anybody else.”

Last week, the Swiss bankers threw in the towel without warning to the outside world to try and limit the amount of unethical trading and manipulation that could have happened if news had leaked. They abandoned the peg and, without an attempt to control the market, the real price was set between willing buyers and sellers.

The result was not a surprise. Investors dumped Euros and shoveled their money into Swiss Francs for a myriad of reasons, not least of which is the potential exist of Greece from the Eurozone, which could cause all sorts of chaos in the short-term. If you’re going to have your savings parked somewhere, it might as well be the strongest and safest economy on the block.

As the Euro began crashing and the Swiss Franc rising, investors started to look around at the various companies in Switzerland that had a lot of earnings in Euros. Those earnings, on paper, were going to be worth a lot less when they had to be translated back to CHF in the upcoming annual reports now that it took more Euros to buy a single Swiss Franc. Worried that the businesses had become more expensive instantly (lower earnings with a stable share price equals a higher valuation multiple), investors started dumping their shares, driving down the stock price of businesses with large exposure to the Euro markets.

Though little had changed in the long-run picture, Nestlé was one of those companies. It is expected to take a significant earnings hit in future periods as all of its snack, chocolate, beverage, food, infant formula, pet supply, and cosmetic holdings in France, Germany, Italy, and the rest of Europe appear, on paper, to be less profitable. The damage? Nestlé, at one point, lost something like 1/12th of its entire market capitalization in a single trading day in the Zurich market.

Simultaneously, the Swiss Franc rose against the U.S. dollar by an amount sufficient to more than offset the decline in Nestlé’s stock price and then some. This resulted in the shares actually increasing in price for American investors despite suffering a large decline in Switzerland.

For the most part, Nestlé is selling the same amount of stuff, at the same profit levels. It just looks bad in Swiss Francs, which is going to make earnings appear to fall and the shares more expensive than they are.

Nestlé Headquarter Vevey, VD – Switzerland. Siège Social de Nestlè en Suisse – Vevey, Canton de Vaud by twiga269 from Flickr. Image made available under Creative Common Attribution 2.0 Generic License

For a business like Nestlé, I think it’s all noise and fury if you have a 10+ year time horizon except that it may give management an opportunity to acquire European assets at attractive prices by moving money from Swiss Francs to Euros. Although it irritated me to pay more, I even bought an additional block of the stock for my own parents’ household account following all the excitement. The economic engine hasn’t changed in any meaningful, long-term sense. The numbers might look ugly, and the stock might appear overvalued going forward, but it is, in my opinion, not indicative of the economic reality in the sense an owner is still getting a heck of a lot of value for his money when acquiring ownership in the firm relative to the stock market as a whole. This is simply part and parcel of making global investments.

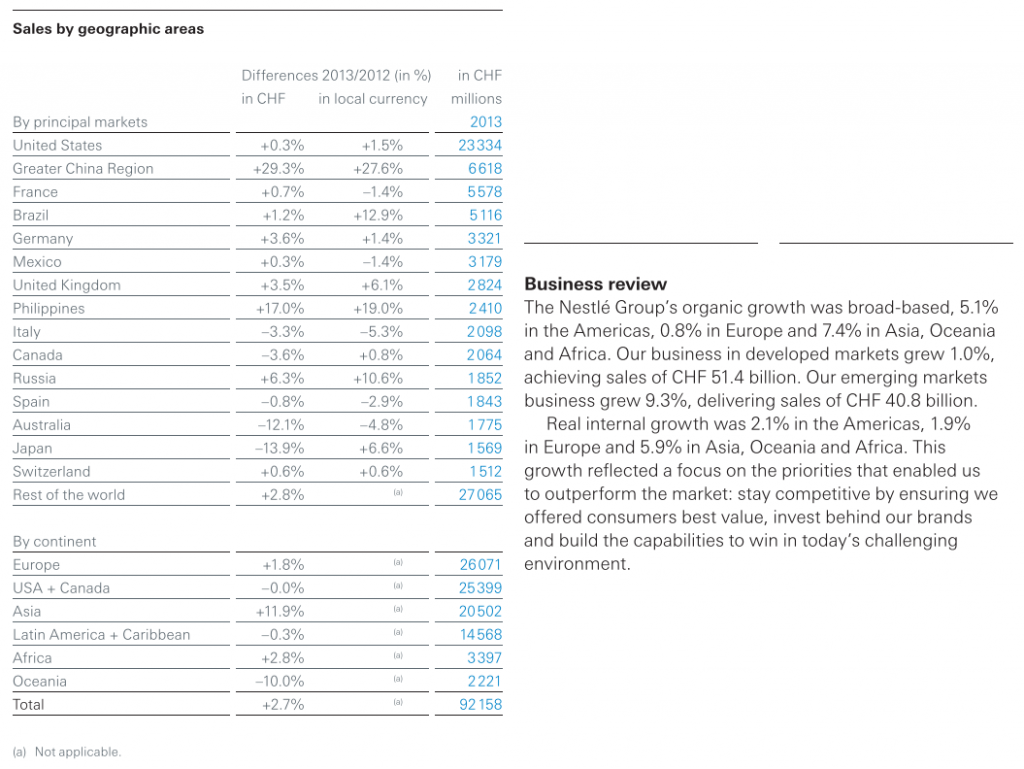

Take a look at 2013’s report disclosures (2014 is not yet published). It shows you how wildly the CHF reported figures can vary from the underlying results in the country itself. (Even this isn’t wholly informative as you really need to look at market share and inflation rates, too, but it serves our purpose.)

Japan provides an excellent example of how actual business results can differ markedly from reported results when dealing with an international company. Japanese revenues were up 6.6% but the movement relative to the Swiss Franc meant Nestlé had to report Japanese sales as being down 13.9%.

American businesses with international operations deal with it all the time, too. If you want to look for a domestic example, look no further than The Coca-Cola Company. The strength of U.S. dollar has caused sales and earnings to appear far worse than they actually are, to the point they are declining year-over-year. It’s a distraction. Diving into the books, you see Coke is right around intrinsic value. It’s neither a bargain nor overpriced for someone who wanted to hold it for the next 25 years, present known factors considered. Currencies go up, currencies go down, but when you have exposure to the entire planet, you want to own more and more of the productive assets that sell stuff to people. As long as you add it to your household balance sheet at a reasonable price, it tends to work out in the end, which is one of the reasons you see wealthy families, in particular, boast portfolio turnover rates that are a mere fraction of the typical investor or mutual fund.

If you’re still decades away from thinking about disposing of your shares, and have plenty of other holdings in a diversified, well-constructed investment portfolio, the recent movement in both Nestlé and the Swiss Franc should have caused you exactly zero concern all else equal. When you read the annual report look at the performance in the local markets over time. That is what counts as the corporation the size of Nestlé will find a way to convert that into purchasing power on the most advantageous terms at some point.

At least that is my opinion. Take it for what you will. The nice thing is that I – and all of you – benefit from people misunderstanding stocks like Nestlé because it allows the shares to trade at a lower valuation than it otherwise would. The p/e ratio gets artificially inflated so it doesn’t show up on stock screens while the dividend yield gets artificially deflated depending on how the programmers of various financial portals treat the Swiss tax rate and the currency conversion.

Finally, keep in mind that, as I said at the beginning, I’m oversimplifying some things. But the heart of the matter is what counts and you should have a much better understand of what, precisely, is going on and why everything was moving about so frantically last week.