The Executives at Edward Jones Should Feel Humiliated About Their Mutual Fund Practices

Trust departments, trust companies, and money management firms provide a valuable service to the civilization. For centuries, men and women who had built up a nest egg could go down to their local branch, meet with the bank, and sign a contract for the bank to protect the money when they were incapacitated or had fallen off the mortal coil. Farmers could sleep at night knowing that the bank would keep their farm running until their minor children came of age. Real estate moguls could have peace with the idea that their spendthrift grandchildren would always have money as they could never touch the principal of their inheritance. Sure, the bank or wealth management company took some fees, but the benefits were well worth the arrangement.

Those who worked in trust departments were typically the epitome of conservatism. Silver haired, suit-wearing, and well-heeled, they sat in their offices, looking over the books, reviewing client portfolios, paying household bills for widows who didn’t know how to manage finances. Their job was to make sure each client owned a collection of assets that suited his or her needs. The laws in the United States held them to a fiduciary duty, including the so-called “Prudent Man Rule”, which requires trustees “to observe how men of prudence, discretion and intelligence manage their own affairs, not in regard to speculation, but in regard to the permanent disposition of their funds, considering the probable income, as well as the probable safety of the capital to be invested.” This was not the realm of high-flying dot-com stocks or options speculation. No, the bank trust officer would put you in stocks and bonds issued by AT&T or Wal-Mart, PepsiCo or Nestle. “Get rich slowly but safely” might as well have been etched into the oft-marble buildings that housed these institutions.

In recent decades, it seems as if things have changed. As I put the finishing touches on an article about bank trust departments I was writing for the Investing for Beginners site at About.com, I decided to pull fee schedules and disclosures from some of the best-known trust companies in business here in the United States. Some behaved very well, still living by that old time religion and keeping the faith. Others, I consider worthy of derision. Let me give you an example of the latter.

The Fee Structure on a Hypothetical $2,000,000 Trust Fund

Imagine you quietly build a $2,000,000 portfolio of blue chip stocks and bonds throughout your lifetime. Year after year, decade after decade, you buy shares of Coca-Cola, Royal Dutch Shell, Procter & Gamble, General Electric, Johnson & Johnson, and a host of other firms with records of growing earnings and increasing dividends. Given that you have no expenses save for a handful of brokerage commissions, academic research indicates you could afford to safely withdraw 4% of your net assets, or $80,000, every year without running out of money even in a Great Depression scenario.

You want your children and grandchildren to inherit these assets, but never be able to do something foolish like lose them to a gambling addiction or day trading. They will enjoy a huge tax advantage when you die because not only will these assets be passed on to your kids and grandkids tax-free, they will enjoy a stepped-up cost basis on the shares, forever wiping out any capital gains taxes you would have owed were the investments sold.

To begin planning this transition, you decide to meet with a trust company. You settle on the affiliate of Edward Jones, the well known and well respected main street purveyor of financial advice. The Edward Jones model allows you to find someone, an individual, you want to work with in your community so you enjoy a one-on-one relationship; a person to understand your needs, hold your hand, and concern themselves with your unique situation.

You look over the terms and, at first glance, they appear pretty reasonable; not a bargain, by any means, but certainly not terrible. To establish the trust and handle all of the details when you pass away, they are going to charge you a $12,500 one-time accounting opening trust settlement and distribution fee. If you need them to act as the executor, as well, that’s another $3,000 on top of it. So right out the gate, $15,500 is gone. For setting up a lifetime of security for your heirs, this isn’t too bad. We’re talking about 77.5 basis points; barely more than three-quarters of one percent. Whatever. We can live with this. Still, you are adamant you want the trust to begin with exactly $2,000,000 so you decide to pay the $15,500 out of pocket from the remainder of your estate.

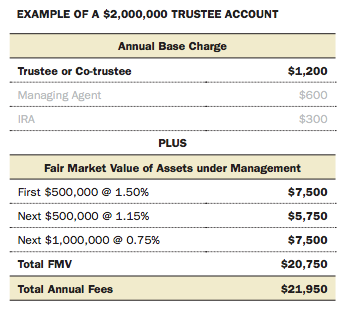

You pass away and your heirs go meet with their Edward Jones representative. Now, the annual fees begin. That’s okay, too. Administering and investing the assets of a trust requires work, legal risk, compliance requirements, and time. To serve as trustee or co-trustee, Edward Jones charges $1,200. Then, to determine the expenses you will pay for the money management fee, it provides a tiered expense ratio that rewards you with larger account balances, which is good. Pulling up their fee schedule (PDF), the first year fees on the $2,000,000 trust would be $21,950, broken down as follows:

Again, not a huge deal. Once the trust is up and running, the base management and administration fees are only going to be 1.1%. That is below the mutual fund expense ratio of the average equity fund, and will continue to decline as the trust assets grow. There will be a few other fees in there – $600 for a preparation of a tax return – but on a $2,000,000 trust, it’s a rounding error.

All in, we might expect the total administrative and investment costs to run around 1.2%. Given that this includes trustee oversight, tax preparation, and money management of a diversified collection of assets (perhaps you instruct Edward Jones to sell some of your stocks so that the trust includes a mix of domestic and international blue chips, gilt-edged bonds, and Treasury bills), that’s more than fair. The commissions are typically free as they use their brokerage affiliate, so you don’t need to worry about those costs. The arrangement will allow the trust company to intelligently plan tax strategy far more efficiently than investing in an index fund could (even the great mutual fund guru John Bogle, founder of Vanguard, points out in Common Sense on Mutual Funds, “Holding individual stocks for the long term may not only be wise, but far more tax-efficient.” When you selectively liquidate certain holdings with the highest cost basis, or shelter certain gains by simultaneously triggering losses on shares that have fallen to net them against each other, you can reduce quite a bit of the bite taken by Uncle Sam, which are among the reasons it’s often better to construct your own index fund from direct securities once you have some real money to your name. One could easily build an S&P 500 fund with as little as $500,000 and a negotiated free commission period).

This is a satisfactory trust arrangement. The withdrawal rate for the beneficiaries will need to be 3%, not the 4% you were taking, in order to safely accommodate the now 1.2% expenses it is running, but you’ve protected the assets from creditors, guaranteed your family will have money upon which they can live, and left an inheritance to even your children’s children so any one who is capable and able will be able to go to college, start a life, and have a little bit extra. Your family doesn’t need to think about stocks or bonds – they may not be interested or they may not have the time nor talent – but they’ll still get to enjoy the wonders of compounding. It’s a mutually beneficial arrangement that is fair to everyone involved.

What’s the problem?

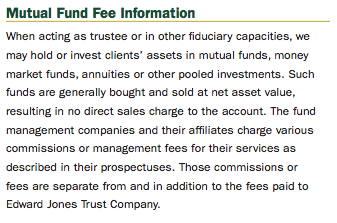

If you keep reading the fee disclosure, you get to a passage that should make your jaw drop.

You, and your family, are paying Edward Jones a tiered asset management fee – 1.5% on the first $500,000, 1.15% on the next $500,000, and 0.75% on the next $1,000,000 – specifically to construct a portfolio of investments for you. This means individually selecting stocks and bonds that fit your needs based on the current attractiveness of the price, while avoiding those that aren’t appropriate for your personality, temperament, risk profile, or liquidity requirements.

Yet, Edward Jones is saying that they might turn around and invest the money into mutual funds.

Mutual funds are pooled investment vehicles through which investors use their combined economies of scale to hire an asset manager. They can be wonderful tools for building wealth, but only if you hold them directly, paying a small one-time commission of a few dollars. In this case, Edward Jones is saying they might take your money, get paid for investing the capital, then instead of doing the job you hired them to do, turn around and hire another asset manager, who will also take a fee, albeit indirectly so you don’t see it as it is deducted from the value of the mutual fund shares. It will never explicitly be listed on your account statement but rather reduce the market value of your mutual fund shares.

It would be like hiring an interior decorator. You put $50,000 in an escrow account to spruce up your house. You agree to pay him $3,000 for his services, leaving $47,000 for the project. He accepts the contract but instead of doing the job himself, brings in another designer. This other designer doesn’t charge you, directly, but instead, adds 10% to the costs of all the rugs, paintings, and furniture she buys for your home. This second designer buys $42,300 worth of stuff, charges you the $47,000, and pockets the $4,700 difference as her fee. But she had a side arrangement that she would inflate the costs of her services then give $850 under the table back to the first designer you hired. And he’d never tell you about this except in teeny, tiny print when forced to disclose it after the government threatened him and levied a hefty fine.

To any intelligent person, the total decorating costs were $7,700 not $3,000 and the first designer was an unnecessary middleman. It would have been better for you to go directly to the second designer, pay the $4,700, and be done with it. It’s also clear the original designer is behaving in a less than honest manner.

At this point, I’m in such disbelief, I think, “Okay. I’ll give them the benefit of the doubt. Maybe, maybe, they will turn around and take advantage of some very low cost index funds or bonds funds, which still doesn’t make sense for any account of size, but we’re talking a couple of added basis points. I mean, the Vanguard 500 Index Fund admiral class shares have a cost basis of 0.05%, or 5 basis points. I can see, in theory, how someone might want to devote a small sliver of an asset allocation to some sort of broad based strategy and the convenience of the prepackaged security would achieve that.” And, again, this is only because we’re dealing with a $2,000,000 trust. For smaller accounts, the pooled structures are probably a necessity as there simply aren’t the economies of scale necessary to get a lot of diversification in a way that is worth the time pf and risk to the firm. If you have a $50,000 account at a financial adviser, you’re probably not getting individual positions.

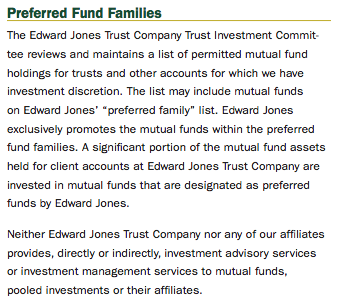

So I dig deeper. Edward Jones has a list of so-called “preferred” mutual fund families. According to the Edward Jones disclosure, a majority of the assets devoted to mutual funds at the firm are steered into those on the list.

JPMorgan Asset Management was recently bragging about being one of the few companies to get on the roster, so I decide to find out which funds are included. Here’s the official announcement flyer from the New York megabank’s money management division:

Click the image to go to the official PDF file on the J.P. Morgan Funds website.

“Alright,” I think. “Let’s pull a random fund off the list. How about the JPMorgan Mid Cap Value Fund? That sounds good. There are two classes of shares, so one of them surely offers a rock-bottom expense ratio since this is an additional cost imposed on top of the Edward Jones management fee and Edward Jones couldn’t possibly be so corrupt or incompetent to pick a regular, plain-vanilla retail fund for inclusion. After all, that borders on professional incompetence to the point if I were a regulator, I’d shut down their trust department.”

[mainbodyad]

Rage. Nothing but rage. The C Class shares have an expense ratio of 1.74%. The A class shares have an expense ratio of 1.24%. The Class A shares have a turnover of 67%, meaning the average stock is held for less than 18 months! Eighteen months! Do you have any idea what that does your tax efficiency? You lose all the benefit of deferred taxes, which can be enormous in the wealth building process. The Class B shares come in at 23%, which is still extremely high. And this is for a trust. Unless you are distributing all of that income to the trust beneficiaries, trusts have significantly compressed tax brackets so short-term gains, if any, are particularly harmful.

Oh, yeah, and Class A shares are so expensive because of the whopping 5.75% sales load. That means for every $10,000 you invest, $575 is taken as a commission charge to the people selling you the fund.

That means that a family with $2,000,000 who went to Edward Jones for investment management services would theoretically be paying an asset-based fee with trust administration fees of around 1.20% plus an indirect fee of between 1.24% and 1.74%, while getting terrible tax efficiency. The only good news is that a client of this size would probably be able to avoid most of the sales loads (it appears, depending on the situation, that once you cross $100,000, the load drops to 3%-4% and once you cross the $1,000,000 mark for a fund, it is exempt), but that is cold comfort to most families.

The combined cut, ignoring the sales load that smaller investors would face, could be as high as 3% to 4% of net worth per year, meaning that the only safe withdrawal rate to survive even a Great Depression for the portfolio owner is 0%. As in nothing. Nearly all of the after-tax, after-inflation rewards are being confiscated by this abomination of an arrangement. And again, for smaller investors, there’s a sales load! This means the best defense a client would have is an Edward Jones representative of integrity, who would choose the lower cost options (not all of the funds have expense ratios this high), while encouraging long-term ownership so any sales loads that charged averaged out to become very small as a percentage of the overall returns (e.g., a 10+ year holding period). As a matter of fact, for a regular brokerage client, there are some interesting mathematical scenarios under which a long-term investor who was capable and willing to hold for more than a decade might end up saving money on fees by opting for the expensive share classes that charge a sales load. It sounds counter-intuitive but it’s true. That is another essay for another day.

This is insanity! I have a hard time believing it exists, let alone that anyone would sign up for these services. I have to be missing something. I have to be making a mistake somewhere, right? Right? Unless consumers were completely stupid, there’s no way the free market could allow it to persist. Right? Why would anyone agree to such terms?

I start researching more.

It turns out that nearly a decade ago, Edward Jones was hit with a $75,000,000 fine as a result of taking “revenue sharing” payments (read: what ordinary people would call bribes or kickbacks) in exchange for steering their customers into the funds of mutual fund families that paid the broker to make the list and never telling the clients about it. The settlement required them to disclose this disgusting practice, which they now do. Here, see it for yourself:

Of course – and this is in no way meant to be a negative as people have much more important things they’d rather be doing in life, which is perfectly okay – the type of people who go to a broker like Edward Jones are the type of people who tend not to be highly sophisticated when it comes to matters of accounting, finance, and economics (Edward Jones isn’t going to be on the top of your list if you are wealthy and know what you are doing as you’d probably be looking for a top-shelf asset management group with whom you would develop a direct relationship) so they probably don’t realize exactly how they are being … is fleeced too strong a word? In any event, I, personally, consider it a violation of the fiduciary duty as well as the prudent man rule because no prudent man would invest this way nor would any trust adviser invest his own money this way if he had any sense of the numbers. The only reason the arrangement is allowed to exist is because of the ignorance of the client. This is not like a hedge fund charging 2% of assets and 20% of profits in a negotiated contract between the investor and the firm; a practice that is clear as day, above board, and everybody knows what they are getting so it’s fair, particularly since it involves sophisticated and/or accredited investors. Unless I’m missing something, this gives me the feeling that it might be hidden, indirect, and obfuscated on purpose.

Let me be blunt: There is almost no situation, that any investor with a meaningful-sized portfolio, under almost any circumstances, for almost any conceivable reason would ever, under almost any condition, be intelligent to pay a money management fee to an advisor then turn around and have the advisor put all of the money into an open-ended retail mutual fund charging another retail-like advisory fee to the fund itself. Furthermore, there is almost no conceivable situation in which an investor should be willing to pay a sales load when the identical fund has other classes of shares not subject to said load, provided the base expense ratios are comparable (they may not be as, again, there are some situations where the load shares are cheaper long-term and you’re better off paying the 5.75% or whatever it is upfront but these are should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis). A handful of exceptions do exist but they are typically involving things like smaller accounts for family members of wealthy clients (e.g., if you have a client with $2,000,000 and they have a college-aged child who has $10,000 in a brokerage account, you might agree to manage the brokerage account for little to no fee and invest it in mutual funds, exchanged traded funds, etc.) or a valuation-specific scenario for those who ascribe to a Benjamin Graham philosophy (e.g., Charlie Munger has talked about there are conditions under which you know an entire sector of the economy is trading for less than its reasonable intrinsic value so you’d buy something like a low-cost ETF focused on, say, domestic and international pharmaceuticals as part of an overall portfolio, which allows you certain economies of scale after all relevant considerations are factored into the decision, in which case the additional fee is worth it. Even I would do that at the right time, under the right circumstances, for the right client if I were managing money as I’d be looking at the bigger picture).

Again, and this is just personal opinion, I think the fact that someone can behave this way is a tragedy. Sadly, even Vanguard’s trust department does it and they are the best of the bunch (don’t even get me started on that – the Vanguard trust department needs some serious work, which disappoints me considering how much I adore the firm’s work and mission. I’d find it very hard to trust them after a fiasco a few years back where they sent a notice that they were changing the beneficiary listed on the IRA accounts of 170,000 clients against the client’s will so they could more easily manage their internal paperwork. It’s entirely possible there are thousands of people out there who now don’t realize they disinherited one or more their children, a spouse, or other intended heirs; an unpleasant surprise when the investor passes away and the family has little recourse). Still, I’m willing to give them a pass. They might not be perfect, but they are the closest thing to perfect I’ve ever seen for those who have modest portfolios.

It seems to me that if you are paying a money management fee, you should get a money management service. I now realize this is apparently not how most of the financial industry feels. The more I look into this, I am clearly in the minority. It’s just that there are better ways to do it. For example, if you wanted your family trust invested in the JPMorgan Mid Cap Value Fund, all you would need to do is hire a corporate trustee or name someone you trust beyond measure and have the trust open a trust account at Charles Schwab, which would work as the custody agent. The trustee then could then instruct the trust to purchase the retail fund or near-retail-priced fund through the account. Other than a small commission, you’d only, then, be paying the expense ratio of the fund itself to the managers of JPMorgan and the administrative and other fees to the trustee, avoiding paying a second, layered money management fee.

Some money managers and mutual funds do have fair revenue sharing arrangements. For example, there are a lot of funds that pay Charles Schwab & Company for promotion. Instead of charging an addition fee, Schwab and the money manager agree to split the fee charged by the fund itself. In exchange, Schwab doesn’t charge a commission on the purchases and promotes the fund on its website. There are really no substantial new, hidden, layered fees; they are dividing up the costs the investor is already paying among themselves. I have no problem with such a true revenue sharing arrangement because the brokerage customers at Schwab aren’t paying Schwab a money management fee of 1% or 2%. There is just one cost: The mutual fund expense ratio. That’s it. That’s all there is too it.

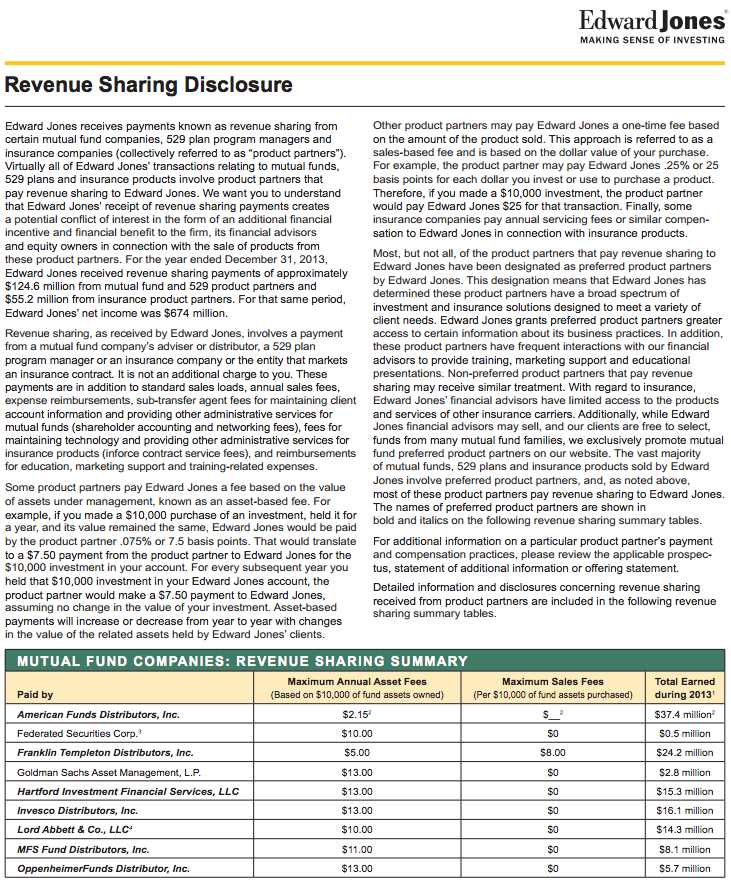

A Look at the Disclosure Document to See How Bad the Damage Is to Edward Jones Clients

So I go to the webpage in the first disclosure document, only to find it’s a broken link. I later find my way to the tiny – we’re talking size 4 or size 6 font I’d guess – link, which then takes me to another page, which then lets me finally find the disclosure PDF containing more details. What does it say? Here’s an excerpt:

Click to go to the original PDF. At this point, JPMorgan hadn’t yet been put on the list but several of the other companies are no better – you can do your own research and look at the added layers of expenses.

There’s the answer. How could Edward Jones purposely steer clients into assets that are shockingly more expensive than they should be, confiscating as much as 30% to 50% of the expected pre-tax and pre-inflation compounding, and virtually all of the after-tax and net-of-inflation compounding? Money. They are, in my personal opinion, betraying their clients’ best interest and getting paid handsomely based on the assets they can gather for other firms. Turns out, it’s not even a secret. The Wall Street Journal has even written about it (PDF).

This is far from uncommon in the asset management industry. Revenue sharing can be ethical, like the Charles Schwab arrangement, but this is something else. Were I a client of Edward Jones, and were I to find a single mutual fund on the preferred list on my account statement, I’d give serious thought to terminating my relationship immediately. If I were particularly fond of my broker, I might compromise and issue a mandate that only individual stocks and bonds can be held in the account as I would hold mutual funds directly, on my own. Good Edward Jones brokers do exist despite the institutional incentives I believe this creates. The trick would be finding one.

There Are Plenty of Honest, Good, Ethical Edward Jones Agents I Would Trust

Let me reiterate that again and be clear: There are plenty of honest, good, ethical Edward Jones agents that I would be perfectly fine having handle an account for the 1.2% all-in management fee on a trust. They would choose excellent long-term stocks and bonds, manage the account with low turnover, intelligently pay attention to tax consequences, and listen to the needs of the beneficiaries. They would make sure the trust was executed in the manner I intended, adhering to my wishes.

My criticism should not reflect poorly on them at all. In fact, the situation is just as unfair to them as it is to the clients because their reputation and business are unfairly sullied through no fault of their own. Some of these people are very talented. They are good, long-term, disciplined investors. They earn every penny of their fees.

Rather, this is about the Edward Jones senior leadership, the upper management, permitting a situation that is directly, irrefutably bad for their clients and that, I believe, exists to fleece them of wealth by preying on their ignorance. There is no justification for it and I think it is a failure of our society to put a stop to it. It wouldn’t even be hard to do. Edward Jones would simply have to setup an in-house mutual fund provided at-cost and available exclusively to clients through the individual Edward Jones representatives. Boom. Problem solved with the waive of a pen.

I don’t understand how people can betray others who trust them. I wouldn’t be able to look myself in the mirror if I acted like this. The Edward Jones senior management is behaving in a way that, to me, indicates they care more about gathering assets than they do about helping clients. They wear the proverbial clothes of a wealth manager but that’s not really what butters the bread. It’s unfair to those who entrust their life savings to them. It’s unfair to the honest, ethical brokers they do have working for them, who refuse to engage in these practices. I personally find whole thing is disgusting.

Part of it happens because of a fine legal distinction between broker-dealers and investment advisors, which this author explains as it relates to Edward Jones. I found that essay after I had finished writing this piece and it does a very good job updating the situation through recent times and explaining some of the potential problems with the Edward Jones model as currently structured. It’s worth the read.

Image Credit: Creative Commons Licensed Under the Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC By-SA2.0). Created by Rona Proudfoot, Edward Jones Investments, aka Star Inc. 2008 Lorain County Beautiful award nominee. Source.