A Case Study of Eastman Kodak

How the Bankruptcy of One of America’s Oldest Blue Chip Stocks Would Have Turned Out for Long-Term Investors

One year ago, Kodak declared bankruptcy after more than 130 years in business as a leading blue chip firm that gushed profits for its owners. I wrote Kodak’s demise at the time.

In the final decade, those profits disappeared and the inevitable spiral into wipeout occurred. Some people use Kodak as an example of how even the best companies can make you lose everything but, in doing so, display the same folly I’ve been warning you about for years: You cannot just look at a stock chart to gauge the performance of a business. You have to do your homework and perform a case study to understand what happened over time.

Before we begin the case study, I apologize for an odd bit in the math: I had wanted to do an apples-to-apples comparison of our case study of General Mills, but after I did the calculations, I realized that I should have begun in 1987 not 1986! With Kodak declaring bankruptcy last year, there was no financial data for 2012, so counting backward ended me one year further in the past than should have been the case. I didn’t catch it until the end and didn’t want to have to redo all of the work.

I performed a few back-of-the-envelope calculations and figured out that it wouldn’t matter much had I begun a year later; depending on the year you invested, you would either add or subtract a percentage point for the most part. That’s a by-product of holding for 25+ years, which is half of an investing lifetime. Starting cost basis figures matter a lot less when you get into the powerful effects of compounding.

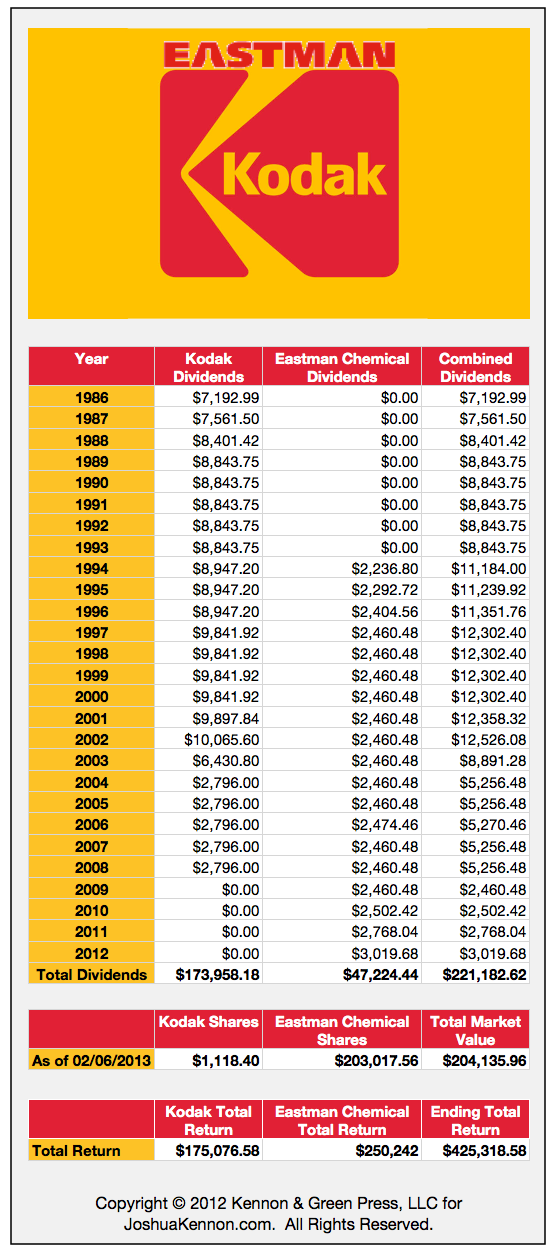

A $100,000 Investment In Eastman Kodak 25+ Years Ago

Imagine it is 1986. You have $100,000 in cash. You decide to invest it in shares of Eastman Kodak, the photography and chemical giant. On the first day of trading that year, January 2nd, you invest the entire amount at the opening price of $26.82 per share. Ignoring the relatively small commission you would have owed, you would end up with 3,728 shares. You have no intention of buying or selling additional shares, so you will incur virtually zero expenses or management costs for the remainder of your holding period.

Over the next couple of decades, three events standout that are of importance to you:

- In October of 1987, shares split 3-2. This brings your total share count to 5,592 shares of Eastman Kodak

- On January 4th, 1994, Kodak spun off its Eastman Chemical division, mailing 1 share to stockholders for every 4 shares of Kodak owned. With 5,592 shares of Kodak, you received 1,398 shares of the chemical business.

- In October of 2011, Eastman Chemical split 2-1, bringing your total chemical shares to 2,796

You do nothing. You sit back for years and collect cash dividends from your investment, which start at a rate almost exactly the same as the then-long-term-Treasury-bond-yields, waiting for the bankruptcy filing shortly after the end of 2011. What happens? How did you fare? Was your $100,000 lost? Let’s take a look.

At the end of it all, before taxes, you are sitting on $425,319 from your $100,000 investment. Of this, $221,863 came in the form of cash dividends, which were mailed to you over the years. The other $204,136 is from, mostly, the market value of the Eastman Chemical shares, with a small amount available were you to liquidate the bankrupt Kodak shares, which have now been delisted.

Not only did you not lose 100% of your money, you actually compounded at around 5.5% per annum before taxes even with the near total wipeout of the Kodak shares. (It’s difficult to say what the after-tax figure would be because it depends on your income tax bracket and whether or not you held the shares in a tax-shelter or retirement plan of some sort. Then, in the midst of this holding period, dividend taxes were slashed to much lower rates than ordinary earned income. At the end, you’d also have a tax credit for the capital loss, which could shelter future income had you held your stock in a plain vanilla brokerage account.)

Had your Eastman Kodak shares been held as part of a collection of high quality stocks, you still would have had fantastic returns. If you put $100,000 into Eastman Kodak and $100,000 into General Mills, 1 out of 2 of your initial stocks would have gone bankrupt and been wiped out to nearly $0 per share. That is a catastrophic failure rate. However, your $200,000 starting portfolio would have ended up worth $2,523,400+ and you’d own shares of a chemical business, a restaurant chain, and the cereal firm. You would have compounded your money roughly 10% pre-tax.

Let me repeat the lesson: You cannot just look at stock charts to gauge the performance of your holdings. Sometimes, you can walk away with more money even though your shares experience a 100% loss. Wipeout losses are always bad – you should do everything you can do avoid them – but they are often not the entire story.

The Bigger Lessons – Warning Bells Should Have Been Going Off Nearly a Decade Before Kodak’s Bankruptcy

As a part owner of the business, in 2000, when you received your annual report in the mail, you would have seen per share profits at $4.59 fully diluted. At the same time, digital cameras were starting to show up on the scene, but let’s imagine you didn’t notice that the days of taking physical film, dropping it off at a drug store or photo labs, and waiting days, or weeks, to pick it up were coming to an end.

In 2003, diluted earnings per share had fallen to $0.83, a drop of 82%.

That should have set off alarm bells because you need to focus on the profits and dividends your businesses generate. Without profits, there can be no dividends. Certainly, good companies are going to experience decreases in profits during times of economic distress but 2003 had already witnessed the recovery of the post-2001 recession caused by September 11th. Things were good elsewhere in the economy.

The falling profit line would have driven your earnings yield down. It would have shown up on your spreadsheets when you saw your portfolio’s share of the net earnings collapsing. That warrants a serious investigation. Good holdings should be increasing that figure over time.

Even worse? Shortly thereafter, Kodak had to restate earnings to $0.66 per share – a huge further decrease! That means something was going horribly wrong and management didn’t have a handle on the accounting records. That is the second major red flag.

The following year, profits fell to $0.28 per diluted share.

To perform the case study on an Eastman Kodak investment, including the bankruptcy of the photography business, I went through almost 30 years of records, adjusted for splits, and added up the dividend accumulations and ending share values. Then I had to double check it all for errors, line by line. This sort of exercise is useful. I would encourage you all do to it if you are interested in businesses.

Think about where you are at this point. The rest of the United States is experiencing a huge boom due to technology and real estate. Life is good. You own 5,592 shares of Kodak that, in 2000, generated net earnings of $25,667, of which $9,842 or so was paid out to you. Now, in 2004, your stake generated net earnings of $1,566 and the company dipped into its reserves to pay dividends of $2,796 to you; profits alone couldn’t cover those distributions.

The profit drop of your stake from $25,667 to $1,566 while the rest of the world is having a party and a major threat (digital cameras) shows up on the scene should have sent you into utter panic. The stock was trading at $32.25 at this point, giving your Kodak shares a market value of $180,342.

You have $180,342 invested in a company that generates $1,566 in profit with that money. You are earning a return of 0.86%. At that exact same moment, the moribund, boring oil stocks that were too big to grow, like Royal Dutch Shell, were offering earnings yields of 9.84% with dividend yields of 4.22%.

Why would you have sat on your hands, owning a company that already dominated its market (in a market that was dying to low-cost digital cameras (in which it would have no advantage)), had no real growth potential, was trading at an insanely high valuation relative to profits and dividends, and couldn’t even figure out its own accounting records, at a time when you could have switched into a boring-as-watching-paint-dry oil giant that generated – literally – 1,000% more profit? Even if you had bought into a firm like BP, which was about to experience the worst oil spill in history a few years later, you would have still come out miles ahead of the game.

It’s one thing to accept those kinds of valuations and risks with a start-up that could make you millions of dollars overnight. It’s patently stupid to accept them as part of owning a large, established, slow growing business in a declining industry.

For me, the huge warning sign would have been the dividend cut between 2002 and 2003, when the 5,592 shares went from generating dividends of $10,066 per year to $6,431 per year. With a further cut to $2,796 the year after that, I think most reasonable long-term income-oriented investors would have been out by 2004. It wouldn’t have mattered if the stock had fallen off its highs; what counted would be cost basis, not the peak of the share price. Despite the troubles, you would have made a good amount of money from your initial investment, plus you’d own the chemical shares. The opportunity cost of holding those remaining 5,592 shares of the photography business would have been too high relative to the competing uses. Kodak should have been jettisoned from the portfolio.

Telling a Kodak from a General Electric or Wells Fargo

How do you separate that sort of development from the dividend cuts experienced by General Electric and Wells Fargo during the Great Recession? Why was I buying more of those firms as few years ago despite the falling profit? In those cases:

- The businesses were not experiencing isolated trouble; there was a macroeconomic superstorm hurting nearly everybody

- The companies were in industries that were growing and thriving, not at risk of becoming extinct

- The businesses dominated their respective competitors

- The businesses had strong balance sheets that would be quickly repaired by using the money that had been going out as dividends to fill the holes caused by the housing bubble collapse

This is why I am so insistent that some people should not own individual stocks – they need to buy only low-cost index funds. If you can’t look at a business and understand how it makes money, and think about the threats to those profits or the opportunities for those profits to grow, you need to stop holding specific equities! You are speculating, even if you don’t realize it. You are going to convince yourself that Wall Street is a giant casino, when the problem is really your own incompetence.

One final warning: We sometimes use earnings yield as a starting point to look at valuation but you cannot rely on it as the sole measure of how cheap a business is. In 2000, when things looked good at Kodak, those $4.59 per share earnings came from a stock price of $39.38, representing an 11.67% earnings yield. The stock had fallen substantially from the year before when the earnings yield was 6.53%. The market was telling you something was going on and you should have paid attention. Kodak was, at this moment, something referred to as a “value trap”.