A Technique for Comparing the Intrinsic Valuation of Two Stocks

One technique I find helps a lot of investors act more rationally is one I developed during my late teenage years. I would convert all companies I was analyzing to $100 per share to make comparison of the figures and yields easier. In essence, this allowed me to ask the question, “How much profit am I buying for every $100 I put into this company?” If I paid a high multiple for a particular business, it forced me to justify the higher valuation by writing down my reasons for my belief.

It might be useful if I show you how I do this. I’m going to take a solid, staid energy company, ConocoPhillips, and a legendary jewelry store, Tiffany & Company, and show you how you could compare the two businesses in a sort of first-pass analysis.

Tiffany & Company is a fantastic business. It has the sort of brand equity that takes a century to build, having turned the “little blue box” into one of the most powerful emotional symbols in the world. ConocoPhillips is also a great business but it has almost no emotional capital – after all, it is harder to get excited about energy than it is a diamond watch given to you on a wedding anniversary. But an investor’s job is to make money, not feel warm and fuzzy about his holdings. That is why I chose these two firms.

Convert Both Companies to a Base Share Price

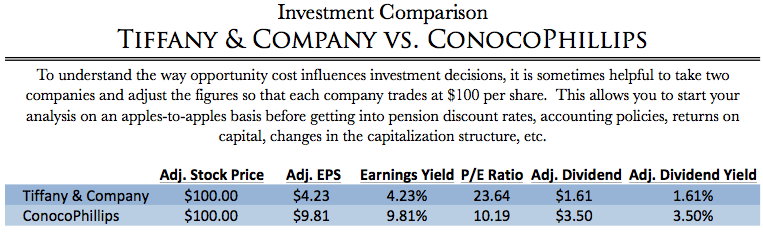

To make the comparison easier between two potential investments, let’s take the data and adjust it as if each stock traded for $100 per share. This helps make the mental process of selecting good investments easier because it forces you to put things into a comparable format. This technique is especially important for investors that have a hard time understanding how a $300 per share stock can be cheaper than a $10 per share stock (if this describes you, head over to the Investing for Beginners site I run for About.com, a division of The New York Times and read “How to Think About Share Price”).

It is easy to make an adjustment like this in a spreadsheet. In my example, I adjusted the figures to see how two unrelated companies stacked up against one another if they were each trading at $100 per share. This allows me to see the data more starkly. (You can use any number for comparison – you could have converted them into $50 shares or $100 million shares – but I prefer $100 because you can just convert the earnings yield percent and the dividend yield percent into the adjusted EPS and adjust dividend yield by changing the % sign to a $; it saves a lot of time.)

On this adjusted basis1, I am faced with a choice:

- I can buy a $100.00 share of Tiffany & Company and get $4.23 in look-through profit, of which $1.61 is going to get sent to me as a cash dividend each year with the remaining $2.62 retained by management to grow the company, pay down debt, repurchase shares, etc., or

- I can buy a $100.00 share of ConocoPhillips and get $9.81 in look-through profit, of which $3.50 is going to get sent to me as a cash dividend each year with the remaining $6.31 retained by management to grow the company, pay down debt, repurchase shares, etc

Always Look at the Underlying Assumptions In the Market Price of a Stock

The “market”, which is really just a way of describing the collective actions of millions of individual investors around the world, is indicating one of a handful of things:

- It believes that Tiffany & Company will grow at a rate that is 132% faster than ConocoPhillips, giving them both the exact same intrinsic value today (e.g., if ConocoPhillips grows at 3%, then Tiffany & Company must grow at nearly 7%), or

- It believes that ConocoPhillips will experience a decline in profitability on a per share basis, resulting in a more comparable valuation between the two firms. This could be due to falling crude prices, a liability the company has incurred (e.g., BP and the Gulf Oil spill), expected dilution in the shares outstanding, or any number of other things that would result in a lower EPS figure in the future, or

- It believes that Tiffany & Company has higher “earnings quality”, meaning that a higher percentage of the reported profits can be converted to cash to benefit the owners instead of being reinvested in lower-returning projects, or

- Some combination thereof

As an investor, it is your job to try and figure out if any of these possibilities is probable. Then, you need to decide whether you think you are being fairly compensated for the risk you are taking by becoming a partial owner in the business.

Develop the Whole Story Before Making an Investment

You would still need to dive into the figures to see if the story was more nuanced than it might first appear; for example,

- Are you falling into the peak earnings trap?

- Does one company have a more conservative capitalization structure?

- Does one management team consistently destroy shareholder value by pursuing high cost acquisitions?

- Are the pension discount assumptions comparable?

- Does one firm generate higher “owner earnings” than the reported profit would indicate?

- Are there any hidden liabilities you aren’t considering?

- Are there any opportunities you are overlooking?

The list is pretty long but the more experience you get, you’ll develop your own list of items you want to check before you commit precious capital to an investment. After all, ten years ago, Apple wouldn’t have looked like a bargain on an earnings yield basis but those with the foresight to see what Steve Jobs would do with the company when he returned to the helm would have adjusted the future earnings for the success of the iPod, the company’s first non-computer consumer device with widespread success that ushered in the rebirth of the company and one of the greatest investment performance runs in history.

The point is, this approach would have helped you avoid the mistake of buying companies like Microsoft ten or eleven years ago when the earnings yield reached an almost unfathomable 1.1% despite being one of the largest companies in the world.

Footnotes

1. Clearly, the readers of my personal blog are far more intelligent than the average Internet user, judging by your choice in reading material, comments, and letters. But just in case you are too embarrassed to ask how the math of such a conversion works because it’s been a few years since you did a lot of math, I’ll walk you through it briefly. (Don’t ever be embarrassed to ask a question, no matter how stupid it may make you feel. Otherwise, you are sacrificing your long-term objectives to your temporary pride. That is a horrible trade-off.) If you have a stock that is trading for $35.00 per share and earns $2.07 in earnings per share, you would take $2.07 and divide it into $35.00. This would give you 0.059142857, which is 5.91% (you just move the decimal point over two places, which is the reason I used a $100 base for the comparison). Switch out the % sign for a $ sign and you the earnings per share for your $100 conversion is $5.91. Repeat this for all of the stocks on your comparison list and put them in a spreadsheet.’

Image Copyright By Bjoern Wylezich / Licensed Through Shutterstock