The Basics of How to Analyze an Investment Portfolio of Individual Stocks or Other Securities

I thought it might be useful to show you how I’d analyze an investment portfolio and calculate a reasonable estimate of not only expected growth in capital but the overall economic characteristics of the holdings.

Tonight, a friend wanted to discuss investments. We’ll call her Alexis to protect her anonymity. We went over a list of stocks that interested her; companies that, for one reason or another, had caught her eye and that she at least wanted to examine. Specifically, she asked us, “If you were me, and you were considering buying this list of stocks, where would you start? How would you think about managing the money? I have $50,000 I want to invest.” Given the nature of the question – her interest in the underlying process from an academic and philosophical point of view – note that I am not going to pass judgment, recommend, or otherwise endorse of any of the securities she listed. (Not that I would, anyway, because as you know I don’t make specific investment recommendations, I try to teach you how to think about important concepts such as valuation and risk to better empower yourself.) This means that the specific stocks she wanted to analyze aren’t the purpose of this post. Rather, the purpose of this post is to let you know how we might begin that process, doing what we do. It naturally follows that some of the companies on her list would not interest Aaron or I. Accordingly, that is irrelevant.

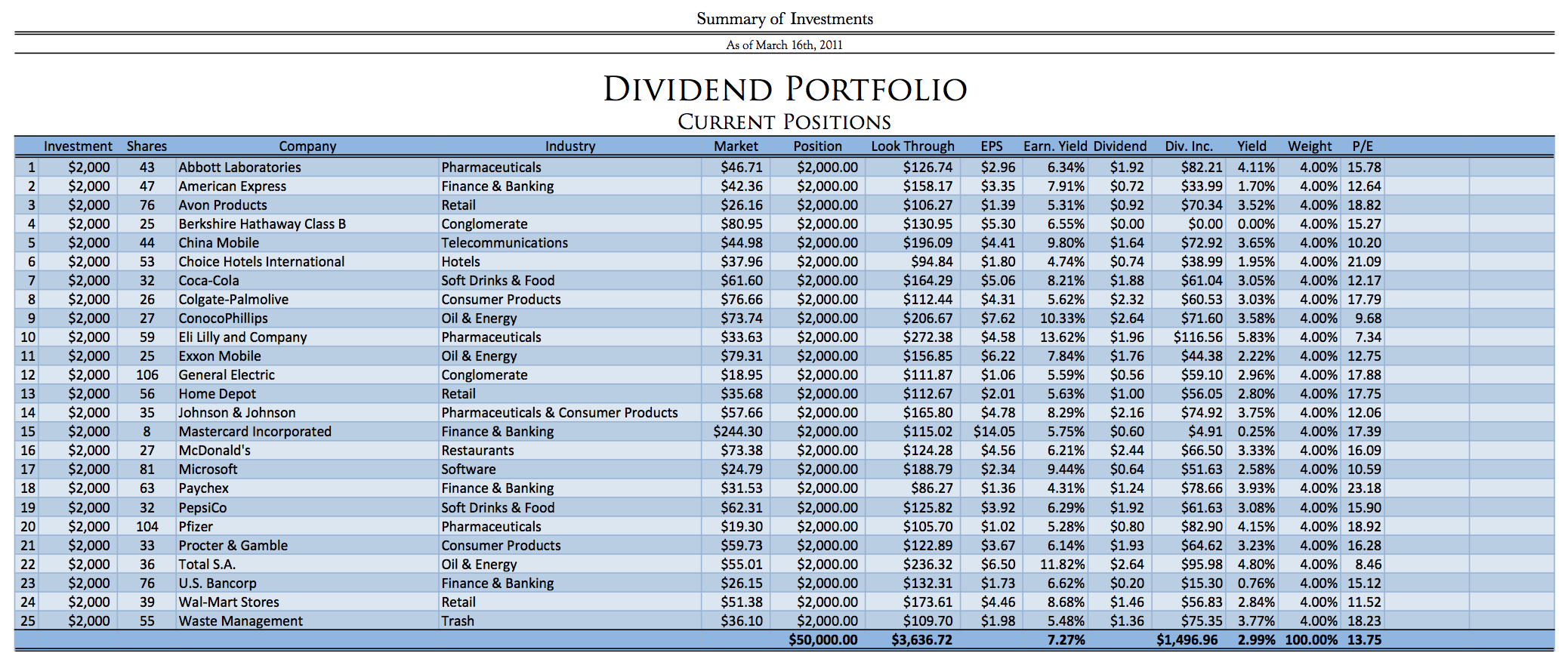

I went into my home study, opened Microsoft Excel on the iMac, and loaded a template that I have used for some time (one of many spreadsheets that I’ve built over the years). I entered her stocks into the spreadsheet and the program did the rest, propagating the information I needed with the following results:

After entering the list of stocks she gave me, this is how I had the information structured in one of my templates. It allows me to start the first-level, basic analysis process of portfolio construction.

The “investment” column is where I entered the amount of money Alexis wanted to invest into each security. Since I was talking in abstract terms about capital allocation, I assumed she put $2,000 into each stock to get an approximation as it would be good enough for our general purpose at the time. Next came the company name and the industry in which it generates most of its earnings. The next column was the current market price of the stock. The next column, “Position”, is equal to the “Investment” column because I use it from time to time to run different calculation scenarios – you can ignore it. The “Look-Through” column takes the earnings per share and multiplies it by total shares owned (it does not deduct taxes that would be owed on dividends if all of this money were paid out, as Buffett recommends, because Alexis wanted to hold the stock through a tax-free retirement account). The column thereafter is “Earnings Per Share”, followed by other metrics such as earnings yield, dividends per share, dividend income for the year based upon the total shares owned, dividend yield, portfolio component weighting, and the p/e ratio. Without further analysis, these are of limited utility – consider the p/e ratio, for example. A stock might be a classic “value trap” and appear cheap for one reason or another, such as a phenomenon known as “peak earnings” in cyclical enterprises. Or, as I briefly mentioned in a post called An Overview of How I Research Stocks, for certain businesses, I’d want to modify the P/E ratio to calculate the Dividend-Adjusted PEG Ratio, instead.

Viewing the Portfolio as a Single Stock

This allows me to look at the entire portfolio as a single stock, or company. In essence, I think of the portfolio as if it were a $50,000 company that earns $3,636.72 after taxes each year, which is a 7.27% earnings yield. Of this, $1,496.96 would be paid out to me, as the owner, representing 2.99% dividend yield. That means the remaining 4.28% of profit each year is retained by the companies to do all sorts of things such as repurchase shares, pay down debt, expand operations (which might include funding research and development to launch new products, mergers, and/or acquisitions), increase salaries, etc.

Watch Your Valuation Multiple / Capitalization Rate Assumptions

“Investing is the process of buying the most future profits for the lowest current price.” – Joshua Kennon

If I assume that the “look-through” earnings can grow by 3% per year, it might be reasonable to project that the portfolio would grow between 8% and 10% annually, over long periods of time (though the ride will be bumpy – the stock market may be up or down 50% from year-to-year). Alternatively, you could always take Ben Graham’s modified formula and use the 7.27% earnings yield + 3% growth = 10.27% long-term compounding. The key here is you are assuming constant valuation multiples! That is, you are assuming that $1 of earnings today will be valued at the same p/e as $1 of earnings 10 years from now, which is a function of the relationship of interest rates to the overall economy. That may or may not be the case and it is important for you to realize the implicit assumption in your forecast.

If interest rates rise, valuation multiples should fall. If interest rates fall, valuation multiples should rise. There are always exceptions but on a broad, macroeconomic basis, this is often the case. This is why dividend yields were much higher in the 1970s and 1980s … inflation was higher and investors demanded the same real, after-inflation return for parting with their savings.

Likewise, this is the reason investor returns were flat between 2000 and 2010. You cannot pay 50x earnings, which represents a 2% earnings yield, for enormous companies like Wal-Mart and Home Depot and expect to do well in any reasonable time-frame. If you do, it was speculation, not investment. Looking at the time period mentioned, even though these firms substantially expanded their profits during the decade in question, the valuation multiple collapsed at a faster rate, resulting in flat or declining stock prices. No rational investor was willing to pay those prices. Although there are always individual exceptions, broadly speaking, you cannot buy large, mature, blue chip stocks stocks when they are offering 2% earnings yields on normalized earnings and expect to earn 20% real returns on your money. It isn’t going to happen under any reasonable set of circumstances. To think otherwise is foolish.

How Fast Can the Companies Grow Their Earnings Relative to Your Valuation Multiple?

On that note, the next question I’d ask myself is, “how fast can the companies you own grow their earnings relative to the capitalization rate applied to the stock?”. A stock that is trading at a 5% earnings yield, or a 20 p/e ratio, growing at 20% is cheaper than a stock trading at a 10% earnings yield, or 10 p/e, growing at 2%. Graham came up with a rough valuation; he said the maximum p/e ratio an investor should be willing to pay for an exceptional company is 8.5 + growth rate. That is, if a company is growing at 12%, the maximum p/e should be 8.5 + 12 = 20.5.

The problem? Right now, that rule wouldn’t work because companies reported enormous losses or impairment charges over the past few years, substantially lowering the level of reported profits. Going forward, those lower figures aren’t indicative of the earnings power of many firms. That is another way of saying that artificially depressed earnings are leading to artificially inflated p/e ratios. You have to understand the relationship between the numbers.

The problem? Right now, that rule wouldn’t work because companies reported enormous losses or impairment charges over the past few years, substantially lowering the level of reported profits. Going forward, those lower figures aren’t indicative of the earnings power of many firms. That is another way of saying that artificially depressed earnings are leading to artificially inflated p/e ratios. You have to understand the relationship between the numbers.

Much of this growth is going to be determined by the way management allocates that 4.28% “retained” look-through profit. As Warren Buffett pointed out in this year’s Berkshire Hathaway shareholder letter, a dollar put in Sam Walton’s hands in the 1960s and 1970s was worth exponentially more than the same dollar of profit put in the hands of the CEO of K-Mart or Woolworth.

On a related note, you have to determine the stability of the earnings power. To use an oft-quoted example, a horse and buggy manufacturer a century ago might have shown good earnings but it was doomed as a long-term investment. I once made this mistake early in my career by buying Borders Group, which remains the single dumbest investment I’ve ever made. By design, we still did well even though that investment did not because our business model and portfolio structure were rational and wise. We put tremendous thought into it. As a result, our net worth and income have grown over time despite volatility in those figures. We want to wake up each day and find intelligent things to do. This means living below our means, seeking to understand the risks of what we are facing, and positioning ourselves so we do better and better over time.

Projecting Ultimate Portfolio Value

For the list of 25 stocks Alexis selected, I would expect growth in the underlying earnings and dividends, taken as a group, to at least keep pace with inflation. That would mean the “real” rate of return would equal to current earnings yield, or 7.27%. If that assumption turns out to be true, 25 years from now, the portfolio should be worth 5.78x the current value in real terms after inflation, or $289,000. At that point, she should be able to switch into higher yield investments with lower growth, earn 5% on the money, and collect $14,450 per year, or $1,204+ per month. Again, that is in today’s money, after inflation, so you can estimate purchasing power. It is also overly simplified for various reasons but we’re looking at high-level academic thought process, not actually attempting to build a personalized financial plan or portfolio. This is about theory and approach, not specifics.

If Alexis were to assume anything above that percentage return in real dollars, I believe it would be delusional. The only way you could achieve something like that would be to enter another asset bubble and be lucky enough to sell out at the top. In the long-run, that is not a formula for winning. It often ends in misery and sorrow.

If I were Alexis in this scenario, and I wanted to make changes to the portfolio rather than build a ghost ship, I’d reevaluate the holdings and reallocate money to the companies with the highest normalized earnings yield (really, adjusted for growth and dividends) every year or so.

You Can Examine and Compare Individual Stocks Using the Same Approach

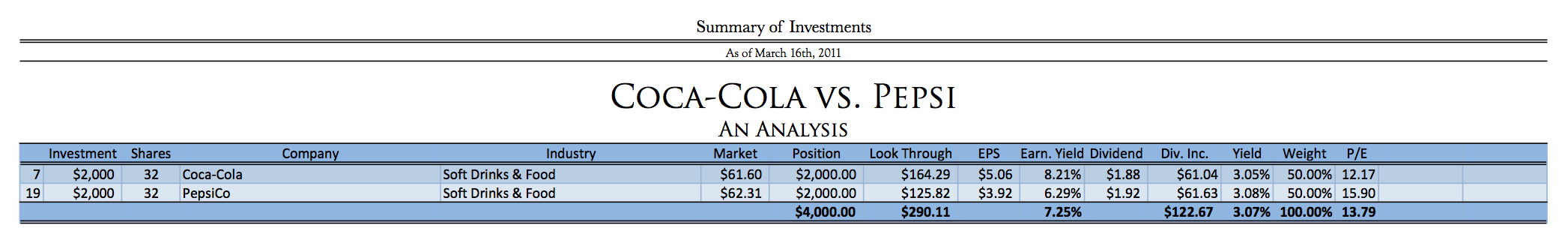

What if you wanted to decide between two individual securities in a specific industry, such as Coke and Pepsi in the soft drink category? (That may not be the best illustration because it is possible you might find the entire carbonated beverage industry attractive – despite its recent troubles, it has produced better long-term investment results over multi-decade periods than a vast majority of American enterprises – so you might consider acquiring the largest three businesses in the space, essentially taking an override on that part of the economy.) You could use the same spreadsheet to create a quick comparison. (Update: A few days after this post was written, I wrote another post in which I shared with you a technique that allows an investor to equalize the figures between two firms for better side-by-side comparisons.)

You could use the same approach to compare two stocks in the same, or even different, industries or sectors.

Your choice comes down to investing in Coca-Cola at an 8.21% earnings yield with a 3.05% cash dividend yield or Pepsi at a 6.29% earnings yield with a 3.08% dividend yield. Which company do you think will grow faster? If the growth rate is identical, Coke, at this price, is a better deal. Over 50 years, an additional 1.92% in earnings yield is an extra 259%.

Of course, it is not always that simple. You’d need to check the pension accounting for both firms – what if one has a fully funded pension and the other is going to need to make up losses? You’d need to check stock option dilution. You’d need to research pricing power of both brands. You’d need to look at depreciation rates on property, plant, and equipment. You might need to examine purchase accounting adjustments for past mergers and acquisitions. The list is extensive. This is known as ascertaining the earnings quality. How much of the reported figure is actually turned into cold, hard, liquid cash that is available to stockholders? All of that is far beyond the scope of what we are discussing but it is an essential part of value investing, portfolio construction, and risk reduction.

There is some subjective judgment, too. Management matters. I’d rather pay a bit more money for a well-run company than a company where I seriously question the capital allocation and shareholder friendliness of the executives (case in point: Kraft Foods). I have so little confidence in the capital allocation decisions of the CEO of that firm that I’d demand a much higher earnings yield and dividend yield to make the investment than I would if her track record were better. Some of you may disagree with me. You might be convinced that the Kraft CEO is an unsung genius who is going to make her stockholders rich. You might be right. I could be wrong. But that is why I said subjective judgment is involved on top of purely quantitative measures. You have to make your own decisions and back them up by risking your own money. This isn’t kindergarten; you cannot rely on other people to do the thinking for you.

Other Adjustments I Might Make to the Portfolio

Think about correlated risk. Consider the assets you hold outside of the stock market (to paraphrase Buffett, “Build Fort Knox.”). Be reasonable in your expectations.

Once I had settled on the portfolio, I’d pull the individual annual reports for each and look for:

- Excessive potential dilution. If the company might dilute shares by more than a few percentage points, I would adjust the earnings yield and dividend yield to account for this.

- Conservative capitalization structure. If the company has high operating leverage or a capitalization structure that matches long-term assets with short-term liabilities, I don’t want to own it in most cases. The earnings might turn out to be an illusion and subject to wipe-out in the event of a panic or meltdown.

- Pricing power and high returns on assets and equity to help combat inflation risk

- Look for correlated risk and, if prudent and possible relative to your objectives, remove it. I would go through each stock on the list and figure out which ones were connected. For example, if 20% of the portfolio consisted of companies located in California, a major earthquake or tsunami there would have a significant and material influence on the market value of my investments. If I owned a ton of oil refiners, power plants, and oil exploration companies, the price of crude is going to present a correlation risk that could expose me to major losses. If I owned all bank stocks, adding a company like Harley Davidson to the mix isn’t diversification because it is essentially a bank or financing company in drag. That doesn’t mean a reasonable and prudent person won’t proceed but it is important to know it and decide whether the risk-reward trade-off makes sense.

- Do some homework to uncover the existence of any more attractive senior issues. During the meltdown, you might have been able to buy convertible preferred stocks in some of these companies with a higher ranking in the capitalization structure, a larger dividend, but almost all of the upside potential of the common stock. In that case, you would have had the same profit potential with built-in loss mitigation. When returns are equal, consider moving up the capitalization structure! Your first goal is to avoid losing money on a permanent long-term basis (which is different from avoiding fluctuations in quoted market price over the short-term). Worry about the profits after that.

- Look for individual modifications to the spreadsheet. From the list of stocks Alexis showed me, I would be incredibly surprised if the dividend rate of several of those components weren’t significantly higher five years from now than they are today. I think they are artificially depressed. Try to load the dice in your favor by collecting companies that are attractive in their own right but that you think have significant potential for upside surprises.

Update: Several years ago, I placed this article in the site’s private archives. However, on 05/21/2019, it was requested that I bring it back as part of a project that I’m doing in my spare time in which I restore access to old posts that have some kind of educational, academic, or entertainment value. This project is a gift to the community. I’m doing it because of the fact that many of you have expressed how much some of these old articles and essays meant to you in your own journey. This piece, in particular, required some minor edits for me to feel comfortable releasing it for several reasons.

Firstly, in the nine years since it was originally published, Aaron and I sold the operating businesses we built and launched Kennon-Green & Co.®, a fiduciary global asset management firm, through which we manage capital for other wealthy individuals and families. Although I have always been clear in my older content, including both on my personal blog and what was then my Investing for Beginners site, that I was not offering investment advice (the original piece was written many years before our wealth management firm was even established and neither of us were involved in the financial advisory business at the time), I wanted to reiterate that fact throughout the piece, adding clarifications that expressed the purpose and scope of what I intended to communicate. While this conservatism should not be necessary – it should be plainly obvious to any reasonable person with any reasonable intelligence who is acting in good faith that this is an academic discussion intended to help people think about some of the problems of capital allocation – it allowed me to feel at peace with the decision to honor the request.

Secondly, at the time this was written, I was sharing a general high-level view of how Aaron and I operated in terms of capital allocation. The actual practices, though, can sometimes be far more intense and far more specific than this. For example, we are primarily interested not in reported earnings per share but, rather, a modified free cash flow metric, which we can then discount and/or compare to overall enterprise value. At Kennon-Green & Co., we have institutional database subscriptions that allow us to apply our preferred valuation models to nearly all publicly traded assets throughout the world. These systems are advanced enough they can be programmed to regularly examine new securities filings and alert us if anything hits our targets. We maintain “shopping lists” of wonderful businesses that we would like to own – companies with extraordinary economics and what we see as strong defenses against competition and/or erosion to returns on capital for one reason or another – updating our approximate estimate of what we would pay if we were able to acquire 100% of it from time to time. We sometimes study entire industries, working our way through the businesses competing in a given space. Sometimes, a business will look attractive but we’ll find a disclosure buried hundreds of pages in its regulatory disclosures that makes us walk away from it because we aren’t comfortable with a risk.

Our capital allocation practices are also aided by other technology. For example, our firm has a sophisticated private client portal that is always under improvement and expansion, rolling out new features quarterly, that allows for interactive data analysis. In addition to advanced performance reporting, and historical research – you can change the date and it will recalculate the portfolio as it was on that particular day in order to provide historical comparisons – the system can project dividend and interest income on a monthly basis over the coming 12 or 13 month period, sorted by a range of preferred presentations including individual asset, sector, industry, asset class, account, strategy, and more. We are willing to make these kinds of investments because they help us be more efficient in serving our clients and they provide the clients with a better experience.

None of those things are available to the (mostly) family and friends to whom we were writing when this post originally went live. My motivation in writing this at the time, when memories of the dot-com boom of the 1990s and the 2007 peak were quite fresh, was to help people put a safety brake on their own propensity to see a company, exclaim, “I like that stock!”, then dump most of their liquid net worth in it regardless of valuation; a behavior pattern I have never understood. Maybe 15+ years ago, I think it was, I called this “the refrigerator problem” on Investing for Beginners because I was astonished to find that data showed most Americans spent more time shopping for a new refrigerator than analyzing their investment portfolio or thinking about ways to achieve financial independence, particularly in retirement. This presentation tool offered some mechanism, no matter how imperfect, to potentially identify companies trading at obscene valuations. It also was intended to re-frame the psychology of Wall Street, emphasizing the underlying operating results of the businesses rather than the day-to-day fluctuations in stock price. Why? Because ultimately, over the long-term for an owner paying cash and avoiding debt, the operating results relative to the price paid are what drive changes in net worth. There might be a lot of fire and fury in the meantime, including periods of 50% drops, but as long as civilization is functioning and capitalism is working, that’s the math. Life is better when you don’t ignore math.